Art of the Genre: Maps and World-Building

Way back in the day, I remember collecting I.C.E.’s Middle-Earth Role-Playing Game. If anyone ever bought those initial MERP supplements, they know that I.C.E. put a photo collection of what products were available on the back [much like TSR listed their products series on the backs of their early modules]. I was young, probably thirteen of fourteen at the time, and didn’t have much money, but I went out and collected everything represented on the back except three things, two of which were the campaign modules, Umbar Haven of the Corsairs and The Court of Ardor in Southern Middle Earth. Both were VERY early in the production line, probably out of print before I even started collecting, and the final piece was the MERP map set. Years later, I managed to purchase both Umbar and Ardor [actually my wife bought me Ardor after my first professional sale], but even though I’ve studied the image on that back cover a hundred times, and longed for the map beneath, I’ve never laid hands on a copy. The concept of that map laid the groundwork for my love of cartography and maps in general.

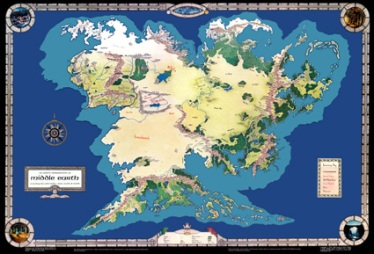

Middle-Earth, as laid out in wonderful topographical detail, was a prime example of how important maps were to a fantasy world, all other books from time-periods after sported some kind of black and white map, and if a book today doesn’t have one it is considered terribly lacking.

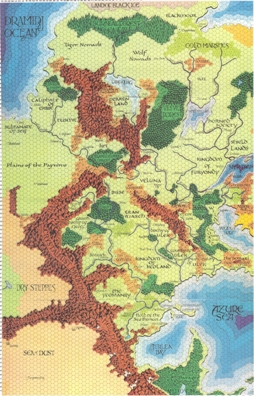

Although I never acquired that MERP map [but if anyone wants to send me a copy, feel free], I did manage to purchase the World of Greyhawk boxed set from TSR that include not one but two huge folding glossy maps of that fantastic world. I’m pretty sure my initial reaction was to freak out and dance around the room, the thought that there was an entire world before me ready for adventure made my life as a gamer so much more real. Up to that point my adventures were all bound to some tiny place, a point of clarity, probably a dungeon, set in a sea of shrouded mist that didn’t allow my imagination true freedom of movement.

I devoured World of Greyhawk, even going so far as to conquer one of the kingdoms as my own [The Tiger Nomads] and drew fortresses, borders, outposts, and such all over my kingdom on the actual map. In fact, I used the map so much, all the folded edges ripped apart and I eventually had to make the hard decision to scrap it [so if anyone wants to send me a copy, feel free].

Another TSR gaming system, Star Frontiers, had released Zebulan’s Guide to Frontier Space in 1985, and that was my first real delve into star maps [not to be confused with those peddled on the corners of L.A. proper for the houses of Brangelina]. The worlds of the United Planetary Federation were shown with transit connection lines behind a kind of nebula backdrop of starstuff, but I couldn’t bring myself to be overly excited about it, something too abstract in the concept as it related to more colorful earthly topography I guess. Don’t get me wrong, I’m terribly moved by space pictures, like from Hubble, but star maps… eh, not so much.

Anyway, by the time I’d finished with Greyhawk, a new world was taking shape at TSR, that being Ed Greenwood’s personal campaign setting The Forgotten Realms. The Realms boxed set, much like that of WoG, had two huge maps, these however weren’t glossy or pre-printed with movement hexes, instead offering clear plastic sheets that could be used when needed to estimate travel time.

The world was lovely, new, and seemingly grittier than Greyhawk. I well remember the first time I saw the box, over in Mark’s living room where his older brother Greg came back from college and told stories of Waterdeep and the North. It was a ‘must own’, and I purchased and played FR with all the passion I could muster in those later days of the grand old eighties. Another interesting note concerning those 1st print FR maps, they DON’T include Icewind Dale, the famed setting for the creation of Drizzt Do’urden by R.A. Salvatore. Newer versions do include this far northwestern outpost, but not the originals, so all those collectors out there, please keep that in mind.

By this time [around 1988], I was finally world-building on my own. My friend Murph asked one day if we could play something ‘different’, both of us being old Basic gamers, Dragonlance lovers, and he hadn’t particularly enjoyed the FR because of a nasty joke I played on him concerning demons when he first discovered the world. Note: This joke was the first time I had a player get up, collect their things, and leave without a word. It was not, however, the last.

To this end, I took a piece of spiral-bound and three-hole punched notebook paper and drew an outline of a continent. This, my dear friends, is the place where DM’s are born, the magical moment when you cease to be a consumer and start becoming a creator. I’d just gone off the reservation, and everything cool I’d ever read about or seen on TV got poured into a world that was so important to me I couldn’t come up with a name good enough to represent it.

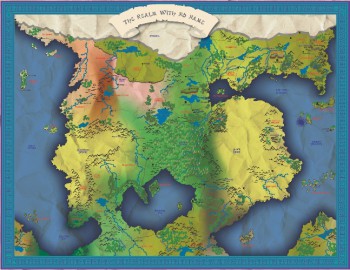

For the purpose of pure identification, I dubbed my creation, The Realm with No Name, and Murph and I started a journey in world development that continues today. I also think that such creation is the fundamental principle in being a writer, because at their core writers create, and they must have a world from which to expand their ideas and stories.

By 1990, I’d filled in my entire continent outline for the The Realm with No Name and was forced to produce a second sheet of paper that detailed lands further to the west. In essence, I doubled my world, and gaming continued unabated as these new lands were explored.

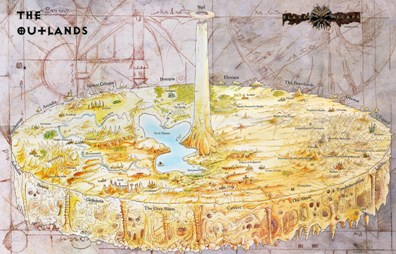

Outside my own world, the pre-made games of the 90s brought several more boxed sets from TSR, namely Dark Sun, Planescape, and Ravenloft, all of whom had very nice world maps, or in the case of Planescape visual charts for the outlands and planes of the multiverse. You also saw in Ravenloft a great map of ‘The Core’, and if you like later additions, you should see that world’s most impressive feature called The Shadow Rift. Gads, even the unyielding explorer in me has absolutely no desire to venture there!

By the end of that decade, however, the need for boxed sets, and the maps included in them, had dwindled as everything went to hardcover core books. These were great reads, had fantastic color art, glossy pages, and everything a player could want, but the maps weren’t overly fantastic. Sean K. Reynold’s masterwork, Forgotten Realms 3E, did have a nice FR map craftily attached inside the back cover and perforated for easy removal, but most game companies simply printed a map inside someplace and left it at that.

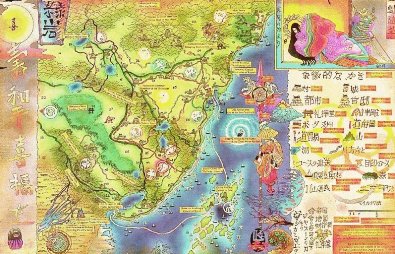

I did some very, very, extensive playing of AEG’s Legend of the Five Rings during that period, but no detachable map was ever provided that I’m aware of, although I did find an outstanding Rokugan map on the Internet, and that seems to be a place most maps are now kept. It’s a nice solution, but to me, much like the concepts of ebooks, there’s just something innately ‘good’ about the tactile experience of rolling a huge map out across a table and running a finger over its surface.

I think it must be a throwback to a time when maps weren’t found on your iPhone, when you kept them [misfolded of course] in the glove-box of your car like some ancient explorer. If I had the wall space, which I don’t, I’d love to frame some of these bad-boys and just hang them around for inspiration. How can’t you get worked up looking at a map that’s seemingly ready for adventure?

Alas, maps today don’t seem to be what they once were, but if you’re wondering whatever happened to The Realm with No Name as the decades passed, I’ll humor you [or me which is probably more likely]. Well, it eventually became apparent that I’d never come up with a cool name for it, and as my players continued to explore, the ‘nameless name’ kind of stuck. Today, I call the place The Nameless Realms, and it eventually expanded to eight sheets of scotch-taped notebook paper before a graphic-designer friend of mine had enough of that and said he’d built it in his computer.

For those of you interested, I’ll share my world map, which I have a huge physical copy of that I tote around in a tube poster protector and often get funny looks from security at airports. As I thought about this article, I ended up contacting some artist friends to find out if they too had created worlds of their own when they gamed. Indeed, each had, and I think my favorite was Todd Lockwood who [and yes, I’d have killed to play in his 1E group] had designed a Larry Niven like ringworld that his players spent the better part of two decades exploring. He also indicated that they only got about two-thirds of the way through the thing, which speaks volumes as to its size. I say bravo Todd, and to all of you who’ve taken out a pen or colored pencils and created something all your own. Maps are the key to unlocking the adventure, and I applaud anyone willing to help in that cause and expand on it in physical form.

I bought two of the MERP Middle Earth continent maps. [dramatic pause] Sadly, I have neither of them now.

As a player, I spent a lot of time pouring over that Greyhawk map, too.

My world creation days started before my gaming days. A friend and I spent many, many hours drawing maps and writing histories to go with them. The ultimate one was on taped-together newsprint, about 4’x6′. Sadly, they were paper training a puppy and…well, we don’t talk about that.

Jeff: You are a cruel man 😉 Tragic about those maps, especially yours! Greyhawk was a beauty map back in the day, and it was so vibrant, which is why I probably saw FR as being a tougher world to play in [which of couse is not the case]

I remember my excitement at getting the MERP map…then being let down that the vast areas seemed to be mostly empty space. Yet when somewhere along the line it disappeared from my gaming collection, I found myself missing it.

As for the Greyhawk map, yeah my group used one of those until it fragmented, then we all chipped in and bought a new set and mounted the pair of maps under plexiglass, with a hardboard backing. We used dry erase markers to track all our adventures and our changes to the world. From the Slavelords to the Valley of the Mage, finally to the end of that nearly two year campaign in the hell that is Tomb of Horrors…it was quite a thing for us to both combine, and fragment, parts of Oerth. (I wonder which of the guys ended up with the boards…and the “history” we created)

I never went for the Forgotten Realms, by the time it was coming around my first gaming group had moved on as we graduated high school…and when I found a new group at college the GM had his own world we were playing in. Sure I bought the hardback Forgotten Realms rulebook, but I never bought the boxed set to get the maps. And once the dependence on the pre-planed world was broken, it was broken forever.

I cant tell how much vellum I used to draw, and redraw, maps during my college years. I think I used my drafting table more for that than for working on my actual designs…and that explains why I never became an actual architect. (btw having access to a blueline machine was nice…)

TW: I have to agree with you, once you start world-building yourself other worlds just don’t compare. Still, if you play a lot of games, then you’ll have to play in other worlds and genres, but again, they will never have the wonder of those first old maps.

Love the story about Greyhawk. That is fantastic!

Scott,

Lately, I’ve been trying to guess what your next topic will be after each Wednesday, but I must confess, I never considered maps. I love cartography, so I found this weeks posting a great read.

Is there any chance I can convince you to tell us a bit more about your map? For example, is that a giant whirl pool in the eastern ocean next to the three islands? If so, what’s the story behind it?

Zachary: Cartography is too much fun, and I’m glad to hear you like it as well! Wow, trying to figure out what I’m going to post about? Good luck with that! 😉

Sure, I can give you some ‘secret’ info 🙂 That is the Kraken’s Maw, a giant whirlpool that I developed early on to thwart adventurers from going to the mysterious islands around it. Initially, the islands were called Cthulhu Isles but I later changed it to Kraken Isles when I was trying to customize and make the map ‘my’ world. Anyway, one of the isles closest to it was where I first DM’d The Isle of Dread out of the Blue Expert Box. The Maw itself also forces ships away from the shore, having them take a route for trade to the south into deeper water. I once designed a sea-trade campaign in this ocean, called the ‘Halo’ because you can navigate in a huge circle around it, and wow is it a fun trip!

I love Karen Wynn Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle Earth, which saw much of its development as a class project for student cartographers, who scoured every scrap of Tolkien’s material for geographical details. Her take on what lies east of the lands traveled in LOTR and The Hobbit is pretty different from the MERP map, and because of my affection for the Silmarillion, I like her version better. It’s less pretty, but more tied in with the ur-narrative. Iluvatar, the creator deity of Middle Earth, put the original humans and elves in specific places to wake up, and then the Valar went and meddled out of good intentions, leaving Morgoth fresh new opportunities to meddle out of nasty intentions. I always thought Iluvatar might have had reasons for putting the first elves and humans where he did, and I wanted to know what happened to the ones Tolkien said had stayed put.

My husband and I ran a sort of mutated GURPS campaign set during the Fourth Age of Middle Earth, with a magic system derived as faithfully as possible from the Silmarillion. It looks like nothing else I’ve seen in RPGs, yet it turned out to be quite playable.

He had a copy of that MERP map, and it’s so pretty, it took some deliberating before we chose Fonstad’s map over it.

Sarah: How nice of you to drop by and provide some really awesome stuff to think on. I read the Silmarillion in High School, and am actually reading it again at this very moment [with 15 other books] but I’ve just gotten to the initial awakening of the dwarves. I didn’t remember it told where each race was placed in the world, and I have to admit that Belariand [ala Children of Hurin] completely confuses me when one considers its location in Middle-Earth. I will, however, say that MERP’s Ardor was an interesting supplement only because it deals with a place totally outside the realm of LOTR or the Silmarillian. We actually get some knowledge of the southern part of the world and the ‘dark elves’ that live there. Good stuff.

Your map and world sound great, and I’d love to hear more about the magic system. I always found MERP to have a strong one because it wasn’t evocation based like D&D, and I assume yours was much the same.

Anyway, thanks for stopping in and I hope to see you again sometime!

Perhaps more than anyone wants to know about our Fourth Age magic system:

We took the Music of the Ainur as our starting point. In that creation story, everything that will ever happen in Middle Earth arises from a musical improvisation that the angel-like Ainur/Valar sing for Iluvatar, before Iluvatar tells them that their song will become a world. Different characters, nations, and family lines have particular affinities for individual Valar, because their lives arise from musical passages that those Valar sang, so we thought of magic skills clustering around the music of their patron Valar.

To sort out which areas of lore and skill to cluster, we spent a long time with the Valaquenta. Once we had a very rough draft of the mechanics, we scoured through the Silmarillian, The Hobbit, and LOTR, and were pleased to see that the text had plenty of passages that could be modeled faithfully with our system. Then we tweaked things a bit more to get the system to feel more like the magic feels when you’re reading Tolkien.

A beginning character might know a touch of Nature’s Ear, with which to hear what trees are telling each other; a more powerful character might additionally know a bit of Nature’s Speech, and be able to ask the trees questions (Have you seen any Entwives in the past century?); a really kickass character who could speak/sing a bit of the Entish language might know Yavanna’s Music, and be able to reach into her line in the cosmic polyphony to find traces of the Entwives’ presence for himself.

Tulkas’s Music will make a mighty warlord of you, but if you want to work your way up to the music that first brought warfare into the world and gave it shape, you’ll need to learn the language of the war Oliphaunts, which will require a few points in the very mundane skill of Play Trumpet (unless your player character happens to be an Oliphaunt).

Yavanna made the Ents, Manwe made the Eagles, etc. We figured the other sentient or near-sentient beings in Middle Earth that were not the direct handiwork of Iluvatar would have been special creations of specific Valar, and would have privileged access to their music. Get far enough into dolphin song, and you can ask Ulmo’s aid directly while you flee the kraken, or perhaps sing a command to the waves yourself.

There were no specific spells. The onus was on the players to come up with cool and plausible ways to apply whatever skills they had to whatever situation we were inflicting on them. Wacky hijinks, of course, ensued.

Sarah: Excellent study in magic, and a pretty wonderful idea in general. I must admit, that for being perhaps the 2nd most popular wizard of all time, Gandolf didn’t use spells. This certainly defines the magic system in Middle-Earth, and I think your take is a sound [no pun] one 🙂 Nice work!

What? No love for Kalamar?

Greylond: Dave Kenzer as well as Knights of the Dinner Table are both well loved here at Black Gate, but the map involved in Kalamar was never something that ‘captured’ me. I’ve heard there was an atlas produced for 4th Edition, but was there ever a physical map done before that time? Sadly, I’ve never had a chance to play Hackmaster 🙁

I got sucked into the World of Greyhawk for many years. Was also a big fan of I.C.E., but didn’t know about this MERP map. I remember being impressed by the Forgotten Realms world, but it was around the time I was moving out of such things. A bit later I found and enjoyed the “Harn” world. I’m not even sure who made it anymore, but here’s a map of the island-continent (a remake, drawn differently), http://cdn.obsidianportal.com/map_images/260846/harn_map_poetic.jpg

Something about Harn worked for me–instead of making gigantic, sprawling worlds, it focused on a Madagascar-sized island, rich with detail. As a business venture I think it quickly failed.

Pfly: You are the second person to bring up Harn. I’m totally not familiar with it, but after taking a look at that map I think I should be 😉 Was it a boxed set? Anyway, thanks for the link, now I have something to do this afternoon!

Excellent post, Scott. Although I don’t think that all writers would agree that creating a map “is the fundamental principle in being a writer, because… they must have a world from which to expand their ideas and stories”, that statement certainly resonates with me. Drawing an imaginary map, whether the creation is completely new or a further detailing of an existing imaginary land, is to me the fundamental act of fiction. The stories and characters that happen within the setting are, to me, far below the world itself, which may have multiple histories, which are meta-stories. I’m happiest with creating a fiction of possibilities, which are what fantasy settings are. Maps are the essential vision of the setting.

I just recently re-acquired a copy of ICE’s MERP (love ebay right now), which was part of my extensive RPG collection as a kid. I’m in agreement that the maps are incredible; I consider them the best of any FRPG I’ve seen. Greyhawk is another setting I had as a kid, and although I never got to play or run a game in it, I enjoyed immensely not only the maps but reading the atlas-like entries about the cultures, and also the pantheon of gods. Similarly, I’ve only recently started paying attention to the Forgotten Realms, and I’m quite impressed with the level of detail in the 3E campaign setting. The maps included with that book are nice, but not my favorites.

I like black ink and linework in general, and maps are no exception. Topographic maps interest me greatly, and the ideal I am striving towards in my own maps is a fusion of topography and old legend-type maps. To that end, this website http://makingmaps.net/category/09-map-symbolization/ is a great resource.

Charles: Indeed, ebay is both the bane and love or my existance 🙂 Glad you enjoyed the article, and I agree there is something primal about nice b/w linework. I think its why I’ve got such a fondness for b/w art and truly, some of the best art I’ve ever seen was done in pencil.