Tales of the Magatama

I bumped into the talented Nick Mamatas at the 2010 World Fantasy Convention and discovered that he was editor for the Haikasoru line of translated Japanese fantasy novels for Viz Media. I might be well-read in foundational sword-and-sorcery texts, but I was pretty uninformed about the fantasy of Japan, and what Nick had to say was quite interesting. I was especially curious about a series of books by Noriko Ogiwara, The Tales of the Magatama, which are hugely popular in Japan, and have won numerous awards.

I bumped into the talented Nick Mamatas at the 2010 World Fantasy Convention and discovered that he was editor for the Haikasoru line of translated Japanese fantasy novels for Viz Media. I might be well-read in foundational sword-and-sorcery texts, but I was pretty uninformed about the fantasy of Japan, and what Nick had to say was quite interesting. I was especially curious about a series of books by Noriko Ogiwara, The Tales of the Magatama, which are hugely popular in Japan, and have won numerous awards.

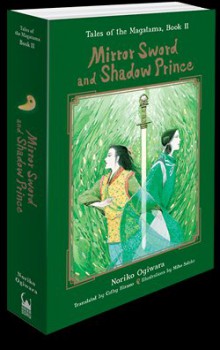

The second novel in the series, Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince, has just been released by Viz, so I thought it high time to talk with Nick to find out more about the series. He was kind enough to answer a number of questions, which I’ve included below.

An interview with Nick Mamatas

Conducted and transcribed by Howard Andrew Jones, May 2011

What drives the plot of the Tales of the Magatama, and who are the characters?

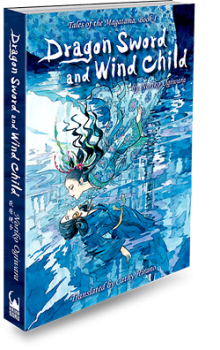

The tales of the magatama are essentially modern revisions of some of Japan’s foundational myths. Both Dragon Sword and Wind Child and Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince are inspired by tales from the Kojiki, a collection of myths from the eighth century. (The myths themselves are even older, of course.) In Dragon Sword, we meet Saya, who is whisked away from her home to marry into the Children of the Light, a species of gods. However, Light does not equal goodness in this story—they murder humans to remain immortal, for example—and the forces of Darkness have many positive qualities. Saya ultimately tries to balance the two.

Mirror Sword takes place hundreds of years later. It is about to young friends, a boy and a girl named Oguna and Toko. Oguna has royal blood and falls under the sway of the mythic sword (it’s called both the Dragon Sword and the Mirror Sword) and only Toko has the power to command magical beads known as the magatama, in order to save Oguna and the land of Toyoashihara itself. This is based on some of the legends surrounding Yamato Takeru, a prince whose adventures are also detailed in the Kojiki.

Not so incidentally, the imperial regalia of Japan consists of a sword, a magatama, and a mirror—these represent valor, benevolence, and wisdom.

The books are richly connected to the mythology of Japan, yet set in an imaginary world, which might explain why some reviewers compare the cycle to The Lord of the Rings, which was set in an imaginary land but drew on mythology of northern Europe. Are there other similarities?

Yes, Noriko Ogiwara was inspired by Tolkien to use the mythohistory of her own country to write new adventures. She was also interested in Buddhism’s arrival in Japan, much the same way many Western fantasists are interested in Christianity’s arrival in the “pagan” world. Saya’s attempt to balance the light and dark is certainly a Buddhist theme.

The first two books are set generations apart – what are the connective threads?

The first two books are set generations apart – what are the connective threads?

The magatama and the sword. The sword is a singular entity—this isn’t a world with a ton of magic items waiting around in dusty corners to be salvaged by the first dwarf who walks by. The Sword is also extremely picky about who gets to wield it. There are a number of magatama, each with their own sphere of influence, and they too cannot be used by just anyone, or for just any purpose. Despite a network of shrines and clan allegiances designed to hold onto the things, it’s extremely difficult to keep track of the magatama, especially since they look like ordinary beads. (PS: Ancient Japan was full of beads; there are villages whose economies are based on bead-making.) Anyway, for the characters in Mirror Sword, the characters in Dragon Sword are almost legendary—sort of like if I started poking around my father’s home island of Ikaria in Greece, on the lookout for burnt feathers and melted earwax from Ikaros’s famous flight (plenty of locals are pleased to point to some random location just off shore and say, “Oh, he landed there”)…and then I found some.

Powerful magical swords lie at the heart of both novels. Will readers familiar with high fantasy or sword-and-sorcery find familiar themes in the stories?

Oh, yes. What does it mean to be a hero? What is “the good”? Can a humble person do great things? These themes are woven into the mythologies of most nations, I’d say, and of course emerge in their modern fantasies. The differences are idiomatic—there’s a certain whimsy and even camp in these novels, which are influenced to some extent by manga, in the same way Western fantasy novels are often influenced by cinema.

You mentioned to me that you thought that the pacing and even the depiction of combat was different from what western readers might be familiar with. Not better, not worse, but different. Could you describe that for our readers?

Think of a Western sword fight. Lots of parrying, clanging of swords, grunting, two men gnashing their teeth as they struggle for position. Now think of a Japanese sword fight. Sword is drawn, slices through the opponent, is replaced into its sheath. There’s an occasional stunning finality to scenes and moments in these books, and in much Japanese science fiction and fantasy, that we don’t often get in the West.

Very interesting. I’ll have to check these out.

[…] DiggIn an interview with Nick Mamatas which Howard Andrew Jones posted on the Black Gate blog, regarding the recent release of Noriko Ogiwara’s Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince (Book two […]