The Lord of the Rings: A Personal Reading, Part One

When I first read The Lord of the Rings I was young enough that I no longer remember how old I actually was. It’s a story that seems to me to have been around forever, a part of the background from which the world was made. I reread it often, though not as often as I’d like; and I’m not sure that ‘reread’ is even the right word here, because every time I go back to it, it’s a new tale.

When I first read The Lord of the Rings I was young enough that I no longer remember how old I actually was. It’s a story that seems to me to have been around forever, a part of the background from which the world was made. I reread it often, though not as often as I’d like; and I’m not sure that ‘reread’ is even the right word here, because every time I go back to it, it’s a new tale.

These are characteristics of a great book: having read it once, you’re drawn back to it again and again; and, once returned to it, you find always something within it that you did not remember. Or else you find a new way of reading it. You are not the same person and the book is not the same book; the rhythm of the plot has a more subtle balance, the imagery aligns in a new way, the characterisation acquires new significance.

I went back to The Lord of the Rings recently, in part because I had some ideas about character and setting and irony, and how they manifest in the book, and I wanted to see if they made sense. That is, I wanted to see if these ideas suggested, not so much a meaningful way to read the book, but a way to read the book to help one approach the meaning within it. I think they did, and now I want to try to work out how and why.

This week I’m going to write about character, next week setting, and then the week after try to consider some of the complex ways Tolkien uses irony. I emphasise that this all presents only a personal reading. I want to describe here what seems to me, right now, to be a useful way of thinking about Tolkien’s accomplishment. It may not be useful to others. Conversely, as I am not a dedicated Tolkien scholar, it may present much that is commonplace. I hope that at least it may present some ideas that will be useful to some readers of this profound, remarkable work.

This week I’m going to write about character, next week setting, and then the week after try to consider some of the complex ways Tolkien uses irony. I emphasise that this all presents only a personal reading. I want to describe here what seems to me, right now, to be a useful way of thinking about Tolkien’s accomplishment. It may not be useful to others. Conversely, as I am not a dedicated Tolkien scholar, it may present much that is commonplace. I hope that at least it may present some ideas that will be useful to some readers of this profound, remarkable work.

The idea about character with which I approached the recent rereading, a very general idea, was simply taking the book less as a novel and more as an example of saga-literature or medieval epic. I think that the approach to character, and to the depiction of character, is very different in Norse sagas than in the modern novel. Sagas are terser, with almost no presentation of the characters’ internal lives; the reader is expected to be able to put things together for themselves from the description of the action. One saga has the protagonist kill another man near the end of the story; at the beginning of the story that man was identified as the uncle of the protagonist — but the fact of the relationship is not brought up when the uncle is killed. You have to be alert enough not only to identify the relationship but also to pick up on what it implies about the protagonist’s background, or what he’s feeling in the wake of the battle.

That’s an extreme example, but I think it’s an approach you can find even in, say, Arthurian literature. As late as Malory you can find the implications of a devastating family feud in the round table, pitting Gawaine and his brothers and cousins against Launcelot, Perceval, and their near relations — but it’s not brought forward in the way most modern writers would present it. Rather than describe emotions festering in somebody’s mind for years or decades, resentments are mentioned only when they incite action.

It’s a type of writing which is not necessarily less concerned with character, or which views characters as flatter than the novel, but one which presents the internal emotions of the characters in a different way. It is, in a sense, the ultimate example of showing and not telling. Arguably it represents a different philosophy of character; one in which character doesn’t necessarily change through various experiences and its reaction to those experiences, but in which character is revealed, sometimes to the surprise of the specific character involved as well as the audience.

It’s a type of writing which is not necessarily less concerned with character, or which views characters as flatter than the novel, but one which presents the internal emotions of the characters in a different way. It is, in a sense, the ultimate example of showing and not telling. Arguably it represents a different philosophy of character; one in which character doesn’t necessarily change through various experiences and its reaction to those experiences, but in which character is revealed, sometimes to the surprise of the specific character involved as well as the audience.

I don’t think any of this is necessarily better or worse than the approach of the traditional nineteenth century novel. In fact probably most works, consciously or not, mix the two approaches. You could argue that the symbolists and then the modernists marked a return in modern writing to the older approach, a concern with the visual image, resulting in the terseness of Hemingway or Carver — perhaps with a greater specific interest in pointing up the discontinuities or uncertainties in character, but then I think much of the power of the approach to character in the sagas comes from the uncertainty the readers are supposed to feel as they try to work out the feelings of the various characters involved.

An example in Tolkien of what I’m talking about is the scene at the Mirror of Galadriel, when Frodo offers Galadriel the Ring. The way I read that scene, Galadriel’s brought Frodo and Sam to the mirror to test them, as she’s aware that they’re the most crucial members of the Fellowship; she may even have foreseen that they’ll be the ones to actually get the ring to Mount Doom. So she tempts them, as the ring might, causing Sam in particular great anguish. Frodo’s reaction is to reject the temptation to leave the quest, and then offer her the Ring. I think that in doing so, he’s neatly turned the tables. I think he’s realised what she was doing, and, recalling what Gandalf said to him about what would happen if the ring were given to a powerful and good figure, tests her in return to see if he can trust her not to give in to the tempation of power.

An example in Tolkien of what I’m talking about is the scene at the Mirror of Galadriel, when Frodo offers Galadriel the Ring. The way I read that scene, Galadriel’s brought Frodo and Sam to the mirror to test them, as she’s aware that they’re the most crucial members of the Fellowship; she may even have foreseen that they’ll be the ones to actually get the ring to Mount Doom. So she tempts them, as the ring might, causing Sam in particular great anguish. Frodo’s reaction is to reject the temptation to leave the quest, and then offer her the Ring. I think that in doing so, he’s neatly turned the tables. I think he’s realised what she was doing, and, recalling what Gandalf said to him about what would happen if the ring were given to a powerful and good figure, tests her in return to see if he can trust her not to give in to the tempation of power.

At the end, both of them know who the other is, but both may be diminished by the experience. Galadriel gently tells Frodo afterward that the Ring gives “power according to the measure of the possessor,” explaining why he can’t use it to know the minds of the other ring-wielders; while when Frodo leaves Lórien, to him Galadriel “seemed no longer perilous or terrible, not filled with hidden power. Already she seemed to him, as by men of later days Elves still at times are seen: present and yet remote, a living vision of that which has already been left far behind by the flowing streams of Time.” I presume this is a function of the renunciation Galadriel made at the Mirror; the Ring-bearer’s progress, however well-meant, has the function of pushing the old magic out of the world.

The point is that Tolkien doesn’t qualify Frodo’s dialogue, does not tell us how to read it or what was in his head. He only says exactly what happens. You can read it and make sense of it as you like — within the bounds of the actions that follow from it, as the book describes. What I have suggested about the Mirror scene seems to make sense to me, given what Frodo knows about the Ring and the importance of the quest. Or you could say that Frodo makes the offer knowing that Galadriel won’t take the Ring, but hoping against hope that she will, and thus free him from the quest. Or you you could say both motives are in play. Or neither.

I think usually Tolkien’s more likely to describe what a character feels or intends in the parts of the story that he’s writing in a more traditionally novelistic style — mainly, the parts dealing with hobbits, who are most down-to-earth. As he moves away from the Shire, the prose becomes more likely to let the characters speak for themselves, in words or in actions. It’s more archaic, in a sense, but a more effective way of describing the world of long-lost kings and elven magics and struggles against balrogs and witch-kings. So by not describing Frodo’s thoughts at the Mirror, Tolkien’s also indicating that he’s entered a grander, more resonant plane.

I think usually Tolkien’s more likely to describe what a character feels or intends in the parts of the story that he’s writing in a more traditionally novelistic style — mainly, the parts dealing with hobbits, who are most down-to-earth. As he moves away from the Shire, the prose becomes more likely to let the characters speak for themselves, in words or in actions. It’s more archaic, in a sense, but a more effective way of describing the world of long-lost kings and elven magics and struggles against balrogs and witch-kings. So by not describing Frodo’s thoughts at the Mirror, Tolkien’s also indicating that he’s entered a grander, more resonant plane.

Modern(ist) writers might use this approach to emphasise the discontinuities of a story, the contradictions within a character, or the unpredictable choices a character might make. But Tolkien, I feel, is less interested in this approach than in describing events, and allowing his readers to shape them into a continuity.

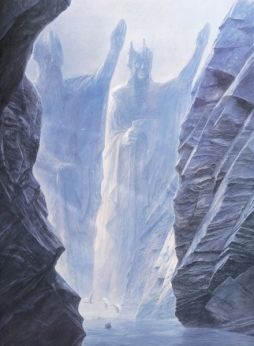

Consider the slow revelation of the nature of Aragorn. We’re introduced to him as a suspicious figure, a ragged ranger, then find out he’s a king in disguise. The nature of that kingship, what it means to the world and to him, only gradually becomes clear. It’s perhaps most dramatic at the Argonath, when we realise for the first time (at least for me it always comes as a surprise, no matter how many times I read the book) that Strider, the hobbits’ faithful companion of the road, is the heir of these colossal stone figures; that he is not only of the culture that made them, but, more directly, these are his forefathers whose kingdom he is returning to inherit:

“Fear not!” said a strange voice behind him. Frodo turned and saw Strider, and yet not Strider; for the weatherworn Ranger was no longer there. In the stern sat Aragorn son of Arathorn, proud and erect, guiding the boat with skilful strokes; his hood was cast back, and his dark hair was blowing in the wind, a light was in his eyes: a king returning from exile to his own land.

“Fear not!” he said. “Long have I desired to look upon the likenesses of Isildur and Anárion, my sires of old. Under their shadow Elessar, the Elfstone son of Arathorn of the House of Valandil Isildur’s son, heir of Elendil, has nought to dread!”

The “strange voice” is an excellent herald of the momentary transformation of Strider into Aragorn. But the next paragraph is:

Then the light of his eyes faded, and he spoke to himself: “Would that Gandalf was here! How my heart years for Minas Anor and the walls of my own city! But whither now shall I go?”

This lightning-fast shift of tone in Aragorn’s dialogue sets up what happens with him through much of the rest of the book, as well as telling us about him as a character — his sense of the past, his relation to his idea of his forefathers, his sense of himself, but also how his desire to see the quest succeed is in conflict with his desire to return to his kingdom. At the start of Book III he complains “An ill fate is on me this day, and all that I do goes amiss,” words he repeats a couple pages later; then a page after that he specifies “Since we passed through the Argonath my choices have gone amiss.” The ancient kings are a support for him, and a symbol of what he can and should be; but they also have knocked something in him off-kilter.

Ultimately Aragorn decides to pause in the hunt for Merry and Pippin he, Legolas, and Gimli have begun, comforting himself with the thought that the whole thing is “a vain pursuit from its beginning, maybe, which no choice of mine can mar or mend.” After the stirring peroration near the end of Book II concluding with the stirring call of “Forth the three hunters!” here he is prepared to seek comfort in the thought that nothing he can do really matters.

Ultimately Aragorn decides to pause in the hunt for Merry and Pippin he, Legolas, and Gimli have begun, comforting himself with the thought that the whole thing is “a vain pursuit from its beginning, maybe, which no choice of mine can mar or mend.” After the stirring peroration near the end of Book II concluding with the stirring call of “Forth the three hunters!” here he is prepared to seek comfort in the thought that nothing he can do really matters.

In fact, you could see his despair even before the hunt began, at the death of Boromir: “This is a bitter end. Now the Company is all in ruin. It is I that have failed. Vain was Gandalf’s trust in me.” (There is a commentary track on the extended DVDs of the Peter Jackson film version where the filmmakers say that they think they wrote a better sequence at this point than Tolkien provided. It’s an unbelievable assessment; Tolkien’s scene is devastating in its unmediated tragedy, Boromir dying believing he has failed, Aragorn unable to comfort him, Aragorn himself thinking he has led the Fellowship to ruin and one of the greatest men of his kingdom to death. But then I remind myself that we’re dealing with people who replaced the wonderful “three hunters” speech with “Let’s hunt some Orc.”) Nevertheless in the end, because of his choices, events turn out right; everybody ends up exactly where they’re supposed to be.

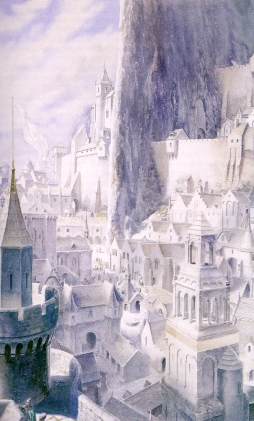

Aragorn’s story through Book III and much of Book V is the slow emergence of his identity as king. I think this builds through various incidents in Book III — his brokering peace between the remnants of the Fellowship and Éomer, his anger but final acceptance of the need to set aside Andúril before entering to meet Théoden — to the moment on the wall at Helm’s Deep when he almost stares down an army: “So great a power and royalty was revealed in Aragorn, as he stood there alone above the ruined gates before the host of his enemies, that many of the wild men paused, and looked back over their shoulders to the valley, and some looked up doubtfully to the sky.”

I think this is in a sense a key moment for Aragorn as a character, in that it seems to me this is the point where he becomes comfortable with his role as king. There’s an irony in the fact that his attempt to cow the opposing army fails, perhaps, but at that moment he acts as an ideal king would. I think many of his trials after that point, specifically in Book V, involve him displaying the inherent qualities of that kingship, if often at some risk to himself — specifically in daring to walk the Paths of the Dead. But I think it’s also important that Aragorn as king first enters his city to heal Merry, Faramir, and Éowyn; not only is there symbolism in the fact that he comes as a healer, but the healing also recalls his attempts to heal Frodo after the confrontation with the Ring-Wraiths on Weathertop, using the same herb. He is what he is and always has been. So when he meets Pippin again, Pippin greets him with a cry of “Strider!” It’s been a long time, it seems, since we’ve heard that name; but it’s as much his name now as it ever was, and he declares that Strider, or Telcontar, “I shall be, and all the heirs of my body.”

I think this is in a sense a key moment for Aragorn as a character, in that it seems to me this is the point where he becomes comfortable with his role as king. There’s an irony in the fact that his attempt to cow the opposing army fails, perhaps, but at that moment he acts as an ideal king would. I think many of his trials after that point, specifically in Book V, involve him displaying the inherent qualities of that kingship, if often at some risk to himself — specifically in daring to walk the Paths of the Dead. But I think it’s also important that Aragorn as king first enters his city to heal Merry, Faramir, and Éowyn; not only is there symbolism in the fact that he comes as a healer, but the healing also recalls his attempts to heal Frodo after the confrontation with the Ring-Wraiths on Weathertop, using the same herb. He is what he is and always has been. So when he meets Pippin again, Pippin greets him with a cry of “Strider!” It’s been a long time, it seems, since we’ve heard that name; but it’s as much his name now as it ever was, and he declares that Strider, or Telcontar, “I shall be, and all the heirs of my body.”

Aragorn, then, is an example of what I meant when I said that character tends to manifest less through growth and more through gradual revelation. As another example, look at Boromir. In that case, the slow revelation of his character resulted in the revelation of the flaw within him. I think, though, it’s easy to focus on the flaw and ignore the gemstone around it. Boromir isn’t a villain, he’s a hero. As it happens, he ends up a tragic hero. Events, one imagines, might have turned out otherwise.

“Boromir isn’t lying,” thinks Sam even after Boromir’s made his try for the ring, “that’s not his way.” The point of Boromir, I feel, is that he’s a hero who falls because of his heroic nature. In part that’s a function of pride, like Roland (whose horn Boromir seems to bear). In part that’s because of the love of his country. You can see the problems his patriotism will lead him to as early at the Council of Elrond, when he gives us such nearly-incoherent encomiums of his people as “Free Lords of the Free.” Ultimately, his patriotism leads to his attempt to seize the ring. He thinks he’s doing right; he loves his country, and aims to see it secure. He acts, at the ring’s urging, out of who he is at the core: the great hero of Gondor. You could maybe argue that he overcomes this self-definition when, too late, he overcomes the Ring’s madness; but then maybe it’s that which breaks him, as much as the orc-arrows.

“Boromir isn’t lying,” thinks Sam even after Boromir’s made his try for the ring, “that’s not his way.” The point of Boromir, I feel, is that he’s a hero who falls because of his heroic nature. In part that’s a function of pride, like Roland (whose horn Boromir seems to bear). In part that’s because of the love of his country. You can see the problems his patriotism will lead him to as early at the Council of Elrond, when he gives us such nearly-incoherent encomiums of his people as “Free Lords of the Free.” Ultimately, his patriotism leads to his attempt to seize the ring. He thinks he’s doing right; he loves his country, and aims to see it secure. He acts, at the ring’s urging, out of who he is at the core: the great hero of Gondor. You could maybe argue that he overcomes this self-definition when, too late, he overcomes the Ring’s madness; but then maybe it’s that which breaks him, as much as the orc-arrows.

I think, though, that you can see what probably would have happened to Boromir over the long term in the figure of Wormtongue. The few comments about Wormtongue’s background we’re given suggest he had a heroic past. Indeed, like Iago, his character makes no sense as a one-dimensional villain; just as Iago had to have something in him to draw Othello’s devotion, so Wormtongue once had to be great enough to become Théoden’s counsellor. Gandalf says “it was not always as it now is. Once it was a man, and did you service in its fashion.”

Ursula Le Guin once made the excellent observation that Tolkien’s evil human (or humanlike) characters tend to be shadows of his heroic characters. Boromir of Aragorn, Wormtongue of Théoden, Gollum of Frodo, Saruman of Gandalf; all are individuated, all are real (though that reality may be shown only briefly), but all have an almost parasitic relationship with someone who is more moral than they, or at least less prone to the temptations of power and evil. I think that fits with Tolkien’s parasitic idea of evil; in fact I think there’s a sense in which Tolkien’s evil is inherently ironic (though irony is not inherently evil). I also think that although evil in Tolkien seems mostly synonymous with the will to power, on a practical evil functions mostly through betrayal and the stirring-up of conflict — leading good people into conflict with each other, or leading good qualities within a person into conflict with each other. And if we see this in Boromir, how much more do we see it in his father?

Denethor might have been the subject of a Shakespearean tragedy; a man of great will and integrity, a man who did not claim the throne he might have had out of respect for the traditions of the past, a man who could face Sauron through the Palantír and stand him off. But a man who drove his sons from him, and a man who came to believe his enemy’s propaganda claiming that there was no hope left in the West. A man who, having come to believe all is lost, finally makes this belief true, and sends his surviving son, Faramir, into a hopeless battle. Faramir’s near-death does what Sauron could not and breaks his spirit, so that all he can think of is the burning of his city and the extinction of his line. All these things are given quickly, in brief, but the complexity of the man is there. One wonders: what would have happened if Faramir had been sent to the Council of Elrond?

Denethor might have been the subject of a Shakespearean tragedy; a man of great will and integrity, a man who did not claim the throne he might have had out of respect for the traditions of the past, a man who could face Sauron through the Palantír and stand him off. But a man who drove his sons from him, and a man who came to believe his enemy’s propaganda claiming that there was no hope left in the West. A man who, having come to believe all is lost, finally makes this belief true, and sends his surviving son, Faramir, into a hopeless battle. Faramir’s near-death does what Sauron could not and breaks his spirit, so that all he can think of is the burning of his city and the extinction of his line. All these things are given quickly, in brief, but the complexity of the man is there. One wonders: what would have happened if Faramir had been sent to the Council of Elrond?

Denethor dies like “one of the heathen kings of old,” insisting on the hour of his own death. After a final wrestle with Sauron (what a scene one imagines!), he is convinced that all is lost. And, though he told Boromir that not ten thousand years would make a steward a king in Gondor, still in his raving Denethor reveals that he will not give up to Aragorn the power that he holds. It is that in part which broke him: the fear of losing his power. And so he commits suicide in a way that destroys the house of the dead — that destroys the past and lineage he has insisted on. Like Faust, Denethor has been subverted by the blandishments of supernatural evil. I said it before, and I’ll say it again: there’s a five-act Elizabethan tragedy in his story.

(Incidentally, with A Game of Thrones now airing, I found myself wondering if Beregond’s treason, drawing a sword on a mad king who insists on the burning of all those around him, was an inspiration for George R.R. Martin’s Kingslayer? Well, you can find echoes almost anywhere, I suppose; is the scene with the Mouth of Sauron an echo of the opening of The Worm Ouroboros, with the insolent ambassador from Witchland?)

(Incidentally, with A Game of Thrones now airing, I found myself wondering if Beregond’s treason, drawing a sword on a mad king who insists on the burning of all those around him, was an inspiration for George R.R. Martin’s Kingslayer? Well, you can find echoes almost anywhere, I suppose; is the scene with the Mouth of Sauron an echo of the opening of The Worm Ouroboros, with the insolent ambassador from Witchland?)

But then there’s also a complex irony that follows from Denethor’s suicide, finding some good in his fall. You have to follow it fairly closely, though: Gandalf is called by Pippin to save Faramir from Denethor, and because he must go at that moment and not confront the Witch-King himself on the battlefield, he tells Pippin, “others will die, I fear.” Still he turns and heads off; he meets the Prince of Dol Amroth on the way, and sends him out to the fight on the fields before the city. Now because Gandalf’s gone off to stop Denethor and save Faramir, first Théoden’s killed by the Witch-King, and then Eowyn’s gravely wounded as she kills the Witch-King in return. The Rohirrim presume she’s dead, but the Prince of Dol Amroth stops them, discovers that she’s alive, and sends her to the Houses of Healing. So because of Denethor’s actions, Eowyn’s wounded and ends up meeting Faramir in the Houses of Healing, meaning that in the end Denethor’s line continues. It is the final, uplifting, irony of his tale; a eucatastrophe in miniature.

I had never seen Denethor’s character as complex as I had before this re-reading; I found, in fact, that almost every time he appeared, some phrase or description caused me to re-evaluate who he was, from Gandalf’s observation that he loved Boromir so much “because they were unlike,” to Pippin’s observation of a similarity between Denethor and Gandalf, to his final moments where he denounces the line of Isildur as “a ragged house long bereft of lordship and dignity” and asserts his right “to rule my own end.” I think much of Tolkien’s powerful, subtle characterisation derives from these startling shifts of perspective; if we think we know a character, if we have decided after an early introduction to them who they are, then we miss the later comments where they tell us plainly who they actually are — and miss the startling feel of the strangeness of the world we thought we knew.

This almost defines the way we look at Treebeard: first a sinister giant, then an absent-minded professor, then something older than the elves, then something like a father-figure out of a fairy-tale. You have to stay alert to all these different aspects to who he is. If, like Tom Bombadil, he seems to be a comforting nature-spirit, then, also like Tom, it becomes disconcerting to see the limits of his power, to realise when all’s said and done his will can be undermined by Saruman. But then again, his letting Saruman flee does lead to the planting of a mallorn-tree in the Shire, so perhaps we should look at him as wiser than we suspect.

Consider also Gandalf. We know who he is. He’s an archetype, familiar from uncountable older stories, not just The Hobbit; he’s Odin and Merlin and who knows who else. But he’s also himself, and those older figures serve not to define him so much as to lull the reader into a possibly false sense of security. For although he’s sharp-tongued, ‘quick to anger,’ he’s also — well, subtle. It dawned on me halfway through Return of the King that he’s the most altruistic character in the book. He doesn’t stand to gain anything. But all his actions, all his manipulations, all his confrontations, even his near-sacrifice of his life, are all undertaken with the desperate hope of bringing the War of the Ring to a good ending (I wonder, in fact, whether the distinction between the Gandalfs Grey and White isn’t simply that the White is thoroughly aware of the cost others have to pay for what the Grey has led them to do).

Consider also Gandalf. We know who he is. He’s an archetype, familiar from uncountable older stories, not just The Hobbit; he’s Odin and Merlin and who knows who else. But he’s also himself, and those older figures serve not to define him so much as to lull the reader into a possibly false sense of security. For although he’s sharp-tongued, ‘quick to anger,’ he’s also — well, subtle. It dawned on me halfway through Return of the King that he’s the most altruistic character in the book. He doesn’t stand to gain anything. But all his actions, all his manipulations, all his confrontations, even his near-sacrifice of his life, are all undertaken with the desperate hope of bringing the War of the Ring to a good ending (I wonder, in fact, whether the distinction between the Gandalfs Grey and White isn’t simply that the White is thoroughly aware of the cost others have to pay for what the Grey has led them to do).

And then I came to his line in Chapter 5 of Book VI: “The Third Age was my age. I was the Enemy of Sauron; and my work is finished. I shall go soon. The burden must lie now upon you and your kindred.” At which point I rethought everything about his character, not once, but four times, one for each sentence. The Third Age was his age; to me that implies that Gandalf looks back on the Third Age as his glory days, the time, not necessarily of his youth, but of his work. And it’s all done now. The Enemy of Sauron; the capitalisation makes it a title. He’s the Adversary of the Adversary. The devil’s devil. His whole nature and reason for being lies in fighting Sauron’s evil. He shall go soon; given his foresight, he knew that everything was wrapping up soon, one way or another: “Naked I was sent back — for a brief time, until my task is done,” he told Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas. He knew that of all the great things of the Third Age that would pass with the destruction of the Ring, all the elven magic and elder races, he would go too. And finally he says: the burden must lie upon you. Which means that he viewed his task as a chore, as a weight.

Does all this make him more heroic or less so? I incline to think more so; I think the line about a burden is the key one (though “the Enemy of Sauron” quickens my imagination the most). For all the thousands of years of the Third Age, he was carrying a burden. Now he gets to set it down. No wonder he laughs so powerfully when Sam and Frodo wake.

Mind you, it’s not only the brief speeches that can cause you to re-evaluate a character. Gimli’s a close-mouthed grim fellow for almost the entirety of the book, joking only over the number of orcs he can kill. Except near the middle of the whole book when he has an extended near-soliloquy about the beauty of the Glittering Caves at Helm’s Deep. It’s his longest speech in the book, and I feel the one in which he most reveals himself — by speaking about the geology of the caves, and what dreams they have fired in him.

Mind you, it’s not only the brief speeches that can cause you to re-evaluate a character. Gimli’s a close-mouthed grim fellow for almost the entirety of the book, joking only over the number of orcs he can kill. Except near the middle of the whole book when he has an extended near-soliloquy about the beauty of the Glittering Caves at Helm’s Deep. It’s his longest speech in the book, and I feel the one in which he most reveals himself — by speaking about the geology of the caves, and what dreams they have fired in him.

I’ll speak more about this next week when I discuss Tolkien’s handling of his setting and his geography, but I think that in these pages he gives us a fittingly rich explanation of who Gimli is. It is precisely because the dwarf’s so close-mouthed before and after that these paragraphs are so moving, showing us his sense of art and his patience in bringing beauty out of stone. He can see cities “such as the mind of Durin could scarce have imagined in his sleep” — but then there’s an ambiguity, perhaps, in the drive to make a city rather than a rural community. He loves the caves, but perhaps there is still something grasping in his sense of them, still a feel for power, still a desire, if not to possess them, then at least to work them. How much is that greed, and how much is that the drive of the artist?

If it’s important not to judge Gimli too quickly, then the same is true of his improbable best friend, Legolas. Again, we think we’ve got a sense of who he is when he says that Fangorn Forest is “so old that almost I feel young again, as I have not felt since I journeyed with you children.” Which means that he’s not as young as he behaves; he’s an old man in young man’s body. Or neither, as he’s actually an elf. What strikes me, though, a) is the admission that he hasn’t felt young since the start of the quest, and b) the off-hand reference to Aragron son of Arathorn, heir to Isildur and rightful King of Gondor, as a child. I think it says something about Legolas, about his sense of his own age, and of the way he looks on the behaviour and actions of the young race to whom his people are leaving Middle-earth.

If I seem to be reading a lot into fairly brief comments, I point back to the beginning of this post. If a character is to be understood by his words and actions, then every word and action must aid in understanding the character. Look at Faramir; he’s a man conscious of the need for honour, conscious that war is not all there is in life, and a man concerned with history — “learned in the scrolls of lore and song,” says Beregond. We can see all this not only in the background about Gondor that he gives to Frodo and Sam, but also just the fact that he gives it to them. His way of dealing with the hobbits is to try and fit them into history as he knows it.

If I seem to be reading a lot into fairly brief comments, I point back to the beginning of this post. If a character is to be understood by his words and actions, then every word and action must aid in understanding the character. Look at Faramir; he’s a man conscious of the need for honour, conscious that war is not all there is in life, and a man concerned with history — “learned in the scrolls of lore and song,” says Beregond. We can see all this not only in the background about Gondor that he gives to Frodo and Sam, but also just the fact that he gives it to them. His way of dealing with the hobbits is to try and fit them into history as he knows it.

More than that, I’d argue that his character is revealed through the way he uses language. You could say that he’s over-conscious of the glorious past claimed by Gondor, over-conscious of the divisions between the different nations of men (and we know it is in division that the Enemy triumphs). But also, more specifically, you get the strong impression that when he talks about kings who “made tombs more splendid than houses of the living, and counted old names in the rolls of their descent dearer than the names of sons” he is speaking autobiographically. When he then goes on to say “in secret chambers withered men compounded strong elixirs, or in high cold towers asked questions of the stars,” one thinks again of his father and the Palantír. So he talks about himself by talking about history. (Ironically, in part by talking about men who were too concerned with history.)

It’s not a question of whether this is a good characteristic or a bad one. Sure, on the one hand you could say it implies a curiosity about the world around him, and on the other you can say he seems overly concerned with the characteristics and divisions between nations of Men. But that’s not the point. It’s neither good nor bad, just who Faramir is. When he learns of Frodo’s quest, he wonders about Frodo’s land and people. When Sam praises him by saying he reminds Sam of wziards, Faramir gently deflects it by saying it is “the air of Numenor.”

So the language the characters use is important. This is of course not surprising. That statement is always true of any careful writer, and I think Tolkien was more careful than most. Tolkien cared deeply about language, and a concern with correct language is everywhere visible in his writing. He uses the language he does to represent precisely the thought processes of his characters; hence the archaism, to reflect the ways of thinking of characters in a specific society. His characters, like Shakespeare’s, use the language they do because it is the simplest, most direct way they know to say what they have to say; and it also, however unconsciously, reveals who they are.

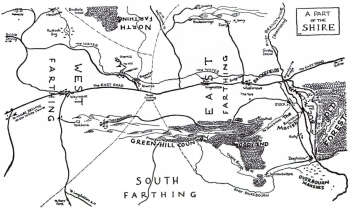

But then what of characters not in such an archaic society? What about the characters of a society perhaps closer to ours? I’ve mentioned that the narrative is closest in tone to a traditional novel (as opposed, say, to an extraordinary post-modern playing-about with the form of saga literature) when it’s dealing with the hobbits. They seem to think most like us, or at least like Dickensian characters — I can’t really explain why, but I always feel Bilbo’s birthday party is somehow weirdly similar in tone and language to Pickwick’s Christmas at Dingley Dell; maybe it’s the story about goblins, or maybe it’s the shrewd servant named Sam. At any rate the point I want to make about the hobbits is this: unlike most of the other characters in the book, we learn about most of their salient points fairly early — but they also grow in the way that we typically imagine characters growing.

But then what of characters not in such an archaic society? What about the characters of a society perhaps closer to ours? I’ve mentioned that the narrative is closest in tone to a traditional novel (as opposed, say, to an extraordinary post-modern playing-about with the form of saga literature) when it’s dealing with the hobbits. They seem to think most like us, or at least like Dickensian characters — I can’t really explain why, but I always feel Bilbo’s birthday party is somehow weirdly similar in tone and language to Pickwick’s Christmas at Dingley Dell; maybe it’s the story about goblins, or maybe it’s the shrewd servant named Sam. At any rate the point I want to make about the hobbits is this: unlike most of the other characters in the book, we learn about most of their salient points fairly early — but they also grow in the way that we typically imagine characters growing.

Merry begins the novel perhaps closest to a fully ‘mature’ hobbit. He’s the squad leader of the group, the co-ordinator of the ‘conspiracy’ to thwart Frodo’s attempt to run away without anybody in the Shire knowing. Before the story properly begins we’re introduced to him in the prologue as “Master of Buckland.” So it’s not surprising, perhaps, to see him grow from being a natural leader among hobbits to a knight of the Rohirrim. He gets to meet Théoden, a real king ruling among his people, and is affected by it.

But Pippin, I think, grows much more. There’s a sense in which the latter two-thirds of the book can be viewed as his Bildungsroman. At the start of Book III he thinks of himself as “Just a nuisance: a passenger, a piece of luggage.” But his quick thinking gets him and Merry away from the orcs. Then he handles and is tempted by the Palantír, bringing him face-to-face (or at least eye-to-eye) with Sauron. Then he finally becomes a knight in Minas Tirith, and ends up saving the life of Faramir before going through a kind of death-and-resurrection experience in the final battle before the Black Gate. In fact, as Book V ends with his loss of consciousness, one can argue that he becomes a kind of symbol or image of all free creatures in the world; the tale cuts from the battle to Frodo, and does not return until the Ring is destroyed.

Sam is yet another case, fascinating because, at least at times, Tolkien presents him with an objectivity and a detailed sense of his interiority in a way we don’t get with other characters. Here’s a paragraph after he finds Frodo paralysed, apparently dead:

Now he tried to find strength to tear himself away and go on a lonely journey — for vengeance. If once he could go, his anger would bear him down all the roads of the world, pursuing, until he had him at least: Gollum. Then Gollum would die in a corner. But that was not what he had set out to do. It would not be worth while to leave his master for that. It would not bring him back. Nothing would. They had better both be dead together. And that too would be a lonely journey.

That sort of extended dramatisation of the internal life of a character is something rare in the book. We never get inside Aragorn’s head in that way, or Gandalf’s, and not even Frodo’s much after Rivendell. Which is odd, as Frodo’s ostensibly the main character of the book. But then again, Sam is the one who manages to both live out a full life among mortals, and also take ship to the West. That may mean something.

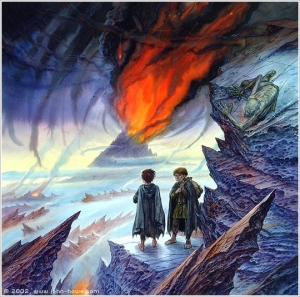

At any rate, Frodo is a much stranger case. The shift from his perspective to Sam’s seems to come about because both hobbits grow as characters over the course of their journey; only, while Sam grows from a pert comic servant into a rounded novelistic character, Frodo grows from a rounded character into something that’s more difficult to grasp. The pseudo-death by Shelob was perhaps crucial, if not the experience of taming Sméagol and seeing what the ring does to its bearers. He throws away a sword in the middle of Mordor, swearing not to strike another blow; and he doesn’t, neither in Mordor nor in the Shire.

Frodo has in a sense moved beyond character; beyond choice. He will bring the Ring to Mount Doom, come what may, so long as he can move. His will may be overriden by the Ring, but not by the pain of his body or any free choice of his own. In a sense, his story’s ended. There is only his success, or his death. For Sam, though, it only becomes clear as Frodo moves through the blasted land of Mordor how far he must go along with his master. He was prepared to take over as Ring-bearer for him. But it begins to look as if he must carry him. And at a certain point, although it is not explicitly raised in the text, the question has to be: will he fight Frodo, if he has to, if Frodo’s will is supernaturally broken, to force the Ring into Mount Doom?

Frodo has in a sense moved beyond character; beyond choice. He will bring the Ring to Mount Doom, come what may, so long as he can move. His will may be overriden by the Ring, but not by the pain of his body or any free choice of his own. In a sense, his story’s ended. There is only his success, or his death. For Sam, though, it only becomes clear as Frodo moves through the blasted land of Mordor how far he must go along with his master. He was prepared to take over as Ring-bearer for him. But it begins to look as if he must carry him. And at a certain point, although it is not explicitly raised in the text, the question has to be: will he fight Frodo, if he has to, if Frodo’s will is supernaturally broken, to force the Ring into Mount Doom?

In the event, it’s a choice he never has to make. Because Gollum is there. Gollum, who has grown from being a monster hiding in the darkness under a mountain in The Hobbit; he’s as much a fully-developed character as the other hobbits, but shown from the outside like the human characters. We overhear him arguing with himself; we see him once, just for a moment, as a withered old hobbit. His long life has been a tragedy mostly spent in darkness; but in the end, despite all the tortures Sauron subjected him to, he gets the only thing he ever wanted — and in the process saves the world.

The curious thing I find about Gollum and his desire for the Ring is this: everyone else who possesses the Ring, or dreams of possessing it, wants it for its power. Even when someone like Galadriel considers holding the Ring, she imagines the power and majesty she will have. And even Frodo asks about the power the Ring could give him. But Gollum, as far as I can tell, doesn’t want to have the Ring to gain power. Even turning invisible would serve to purpose to him, underground. He wants the Ring for itself. Nothing more. And, in the end, he gets it.

I’ve tried to indicate in this post some of the complexities of some of the most notable of Tolkien’s characters. There is much more that could be said, and this post has already become very long. But I want to make a couple more points before wrapping up. Firstly, I think that Tolkien’s character-work is perhaps not as widely recognised as it ought to be precisely because he gives his characters almost too much individuality for any one story to hold them all. In a sense, The Lord of the Rings is a vast anthology, a story with many other stories inset within it or crossing over into it and back out. Like Dietrich of Bern appearing briefly in the Nibelungenlied, Arwen Evenstar appears only briefly in the main text of The Lord of the Rings; but you have as much of her as you need. She enters at the end; and then you realise part of what has driven Strider all through the War. She is not a part of the story, properly speaking, but he is.

I’ve tried to indicate in this post some of the complexities of some of the most notable of Tolkien’s characters. There is much more that could be said, and this post has already become very long. But I want to make a couple more points before wrapping up. Firstly, I think that Tolkien’s character-work is perhaps not as widely recognised as it ought to be precisely because he gives his characters almost too much individuality for any one story to hold them all. In a sense, The Lord of the Rings is a vast anthology, a story with many other stories inset within it or crossing over into it and back out. Like Dietrich of Bern appearing briefly in the Nibelungenlied, Arwen Evenstar appears only briefly in the main text of The Lord of the Rings; but you have as much of her as you need. She enters at the end; and then you realise part of what has driven Strider all through the War. She is not a part of the story, properly speaking, but he is.

Consider also the Council of Elrond, where a range of characters share stories, ask each other questions, and slowly work out the overall shape of events. Farah Mendlesohn, in her book Rhetoric of Fantasy, argued that most portal-quest fantasies (like The Lord of the Rings) suffer from having a single character explaining with perfect accuracy the nature of the world to a young or naive protagonist; this is a problem, she contends, as it denies the multiplicity that makes up the world, the process of argumentation and negotiation by which one comes to grasp reality, and substitutes a specious and facile single-sourced authority. I can’t help but oversimplify in presenting her argument so briefly, and the book as a whole is worth reading; but my point is that the Council of Elrond is an example in Tolkien (here, as so often, much more radical than any of his imitators) of just that process of negotiation. It’s a series of stories, overlapping, told out of order, working together to make up a world. The Lord of the Rings as a whole has something of that feel; multiple tales, coming together, making a whole tale grander than any one of them or indeed than the simple sum of them together. The framework of the War of the Ring becomes grander precisely because it contains so many grand stories: Denethor, Arwen, Aragorn, Frodo, Sam, all with their own stories, and their own kind of story.

Before wrapping up, I want to return to where I began. I said that it ocurred to me to read Tolkien as one reads a medieval text. In that context it may be worth considering some of what Tolkien’s great friend C.S. Lewis had to say about medieval literature. Lewis and Tolkien presumably shared a similar outlook on the middle ages; Lewis’s comments on medieval writing might also therefore apply to Tolkien.

Lewis, in his book The Discarded Image, said that in much medieval work “the writing is so limpid and effortless that the story seems to be telling itself. You would think, till you tried, that anyone could do the like.” We certainly have a few decades worth of testimony to how difficult it is to imitate Tolkien, but I do think there is a sense in his work of effortlessness. That’s remarkable, when you think about it. He moves between styles in a highly unusual way, and often between relatively difficult styles, or at least styles unfamiliar to most modern audiences. His vocabulary’s extensive. But whether people like reading Tolkien or not, nobody complains that he’s difficult.

Lewis, in his book The Discarded Image, said that in much medieval work “the writing is so limpid and effortless that the story seems to be telling itself. You would think, till you tried, that anyone could do the like.” We certainly have a few decades worth of testimony to how difficult it is to imitate Tolkien, but I do think there is a sense in his work of effortlessness. That’s remarkable, when you think about it. He moves between styles in a highly unusual way, and often between relatively difficult styles, or at least styles unfamiliar to most modern audiences. His vocabulary’s extensive. But whether people like reading Tolkien or not, nobody complains that he’s difficult.

Lewis goes on to argue that the typical medieval imagination “is a realising imagination. Macauley noted in Dante the extremely factual word-painting … Now Dante in this is typically medieval. The Middle Ages are unrivalled, till we reach quite modern times, in the sheer foreground fact, the ‘close-up.’ … I mean the young Arthur turning alternately pale and red in Layamon, or Merlin twisting like a snake in his prophetic trance … the medievals had hardly any models for it, and it was long before they had any successors.”

This is what I find in Tolkien, and this is how I find he builds his characters. The telling image. The precise word-painting. Tolkien is re-creating early medieval writing, and it seems to me that he is doing it uncommonly well.

Two last points from Lewis. Firstly: in his book The Allegory of Love he examined the late-medieval tradition of writing on courtly love — a literary theme which began in the twelfth century and which still affects the way we write and think about love. Lewis elsewhere made the point that to read medieval writing rightly “you must suspend most of the responses and unlearn most of the habits you have acquired in reading modern literature.” This is what I am arguing for Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings — which, incidentally, being inspired by writing which predates the courtly love tradition, seems (almost unique among writing of the last eight or nine hundred years in being) untouched by that way of thinking about love, that sense of the importance of love.

Two last points from Lewis. Firstly: in his book The Allegory of Love he examined the late-medieval tradition of writing on courtly love — a literary theme which began in the twelfth century and which still affects the way we write and think about love. Lewis elsewhere made the point that to read medieval writing rightly “you must suspend most of the responses and unlearn most of the habits you have acquired in reading modern literature.” This is what I am arguing for Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings — which, incidentally, being inspired by writing which predates the courtly love tradition, seems (almost unique among writing of the last eight or nine hundred years in being) untouched by that way of thinking about love, that sense of the importance of love.

Secondly: in that book, Lewis argued that medieval writing did not necessarily disdain unity of form: “If medieval works often lack unity, they lack it not because they are medieval, but because they are, so far, bad.” But when it’s good, he says, “medieval art attains a unity of the highest order, because it embraces the greatest diversity of subordinated detail.”

And this is what I find in Tolkien. I have never heard anybody claim that The Lord of the Rings is not a unity. But after almost half a century of people trying to imitate his achievement, the real variety and diverstiy of the book is ignored or missed. It ranges over characters, forms, and styles covering at least a thousand years of English literary history. You don’t need to know any of it to enjoy the book. But the point is that there are different aspects to it, different approaches, a staggering variety of form.

I’ve tried in the above post to indicate some of that dizzying variety, as I find it in his characters. There is much more to be said, of course. And I will try to say some of it next week.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

A nice, long (no complaints there) thoughtful posting.

I enjoyed it quite a lot, and look forward to the next installment.

Thanks for the insights.

For me at least, these types of articles are why I come to Black Gate. 😉

Your conclusions might be different if you incorporated Tolkien’s entire work into your musings. For example, Denethor is not the first Steward to deny a claim to Gondor’s throne by an heir of Isildur. Denethor’s actions hint at, even as they perpetuate, the history of internal strife within the Dunedain that worked so much evil.

The same could be said about Gandalf and others. While character is revealed, so is the rich history of the setting.

Also, I don’t think Tolkien deliberately set out to use irony in the way you described. Some of the examples you used would more accurately be described as Tolkien portraying how God can bring good out of an evil situation and that His plan will often unfold in unexpected ways.

Thank you kindly for your essay. I enjoyed it very much. I will post a link to it from our site, The Literary Role Playing Game Society of Westchester.

:)Sincerely,

VBWyrde

Gruud and VBWyrde, thank you both for the very kind words!

Tyr, I take your points about Tolkien’s other work. I did want to try to read LOTR almost ‘in isolation’ this time round. I certainly agree that his ability to play with the history of the setting is one of his most remarkable characteristics — the way he can have one story in his legendarium inspire another, the way stories can contrast or develop each other, the way one story can rework or extend the themes of another. But this time around, I wanted to try to understand LOTR itself as a story, so that in another reading later on I’ll be able to fit it into the overall shape of his work.

With respect to Denethor, you’re right that it’s another example of the conflict within the descendants of Numenor, and for that matter another example of the way evil works by stirring up conflict among the well-intentioned. I think what startled me about him rejecting Aragorn was that Denethor personally seemed to have a lot invested in his identity as steward rather than king — I think it’s key that, as a way of describing Denethor’s personality, Faramir tells Frodo the story about him telling Boromir that ten thousand years would not suffice to make a Gondorian steward a king. I think everything we see about Denethor up to his death scene tends to confirm that impression, in the sense of establishing the significance to him of history and custom. So to see him rejecting that history in favour of his own power, was, to me, startling.

And about irony: the thing about irony is that there are probably something like half-a-dozen different valid definitions of what irony is. I plan to be more precise about how I mean the word in the third post. But for the moment I’d say I don’t think we disagree much; it’s just that I would use ‘irony’ to describe the way in which good comes out of evil. It’s tragic or dramatic irony made comic. Or, if you prefer, divine.

As I was reading your last comment (you’re quite welcome) it occured to me that there may also be hints as to the character’s natures in their names. You didn’t discuss that aspect, but I think it is worth a mention. Gandalf may well translate as “grand alf”, and in fact in celtic literature I believe there was a Gandalf. Frodo also comes from Norse mythology, though I don’t at the moment remember the exact source. I’d be curious to know what the roots of the names Denethor (obviously Thor, but the Dene prefix may be meaningful), and Aragorn, not to mention the names of the Dwarves which also stem from actual myths in at least a few cases. Anyway, mapping back to the name-sources may provide additional insights to the character’s natures. Oh, and I’d also be even more curious about any names that do not have a mythological source, since those would be ones that Tolkien devised himself, and possibly with additional depth of meaning behind them. Just a hunch, though. No idea if that bears any fruit, but I figured I’d pass on the thought just in case.

The names are interesting, because they do have specific sources (some in this world and some in Tolkien’s invented languages) and often very direct applicability. Tom Shippey wrote a fair bit about this in his book J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. Some highlights: Gandalf means ‘staff-elf’ (or so Tolkien seems to have thought; I’ve seen some suggestion online that ‘gand’ or ‘gand-reid’ means ‘magic’ and ‘ganda’ means ‘magic wand’), Saruman means ‘cunning man’ (with the ‘saru’ being a word that also seems to refer to cunning working with metal) and orthanc is ‘cunning thought,’ and Frodo is a name out of Norse story that appears briefly in Beowulf. Shippey’s book is excellent, and really worth reading to see how he explains the meanings and resonances of all these names.

The Tolkien Gateway, at tolkiengateway.net, also has a lot of etymological information on various names. I note that Denethor apparently means “lithe and lank,” which makes me wonder if it’s a nod towards ‘longshanks,’ a nickname for Edward I.

Hope that helps!

Nice work here Matthew, very enjoyable first installment and I look forward to the others. Like you, I never get tired of reading The Lord of the Rings (nor reading others’ thoughts and analyses).

I think viewing the text as a medieval romance mixed with norse saga is a great way to approach LOTR. Many complaints revolve around the fact that LOTR does not read like a modern novel; it’s helpful to know that writing a modern novel was not Tolkien’s intent (though he did use some very modern literary techniques, and you could say it’s a comment on modernism).

I think that Tolkien’s character-work is perhaps not as widely recognised as it ought to be precisely because he gives his characters almost too much individuality for any one story to hold them all.

Yes, absolutely! Though there are many reasons the Silmarillion isn’t as successful as LOTR, Tolkien’s characterization of Galadriel in LOTR always had the echoes, for him, of the work he’d done for years in the manuscript he couldn’t publish. When Frodo offers her the ring, she has a whole pack of brothers to remember who met tragic ends and brought others down to ruin with them because of their will to power. Her determination to protect the home she’s made in Lothlorien reaches back to her Shackleton-worthy trek across the grinding ice of Helcaraxe. You couldn’t make a five-act tragedy out of all that, but it would have been a fine memoir.

[…] is the second of three posts prompted by a recent re-reading of The Lord of the Rings. As I said in the first post, I went back to the book with the general idea of approaching it as one would a medieval saga, […]

[…] re-reading of the book. You can find the first post, looking at Tolkien’s sense of character, here; the second post, about Tolkien’s use of landscape, is here. This week I’m going to write about […]

[…] Reading” caught my attention, particularly in light of Matthew’s intriguing series of essays on Tolkien. (I haven’t commented upon them yet because they are sufficiently deep to require a second […]

[…] House was a failure because it wasn’t fourteen lines long and divided into an octave and sestet. I’d argue that Tolkien’s understanding of character is no less deep than what we find in the rea…; but his way of bringing out character is certainly […]