Analog, February 1966: a Retro-Review

And now the third of three consecutive months of SF magazines I recently bought, each a different specimen of the canonical “Big Three” of that time. The first, the December 1965 Galaxy, is here, and the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is here.

And now the third of three consecutive months of SF magazines I recently bought, each a different specimen of the canonical “Big Three” of that time. The first, the December 1965 Galaxy, is here, and the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is here.

Todd Mason complained last time about this designation of Analog, Galaxy, and F&SF as the “canonical Big Three” SF magazines of the ’60s. He noted, correctly, that Galaxy‘s sister magazine If was winning Hugos as best magazine, and that Amazing and Fantastic were tremendous magazines under Cele Goldsmith Lalli (though by 1966 the magazines had been sold and Lalli was no longer editing them — and their quality suffered immensely).

Fair enough comments — but there is little doubt that Analog, Galaxy, and F&SF were regarded then — even by those who voted for If for the Hugo! — as the most prestigious SF magazines in the US. They paid better. Analog and Galaxy published more fiction per issue, though F&SF was as slim as If and Amazing/Fantastic. They were regarded as more “serious” — each in different ways, mind you. (And I think that very lack of seriousness was a big part of If‘s appeal.) Anyway …

This issue of Analog comes very late in John W. Campbell’s long tenure. The magazine is all but universally regarded as having declined in quality by this point, relative to Campbell’s best years. But this issue is really quite a good one.

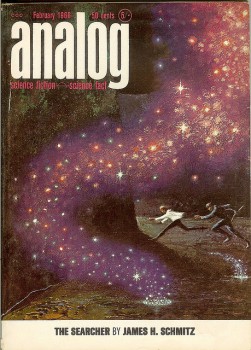

The cover is by Kelly Freas, illustrating “The Searcher”, by James H. Schmitz. Interior artwork was by Freas mostly, and also John Schoenherr. Analog featured a few ads: for the Science Fiction Book Club, for Edmund Scientific, for Simon and Schuster’s The World of Mathematics, and a PSA about good driving.

The cover is by Kelly Freas, illustrating “The Searcher”, by James H. Schmitz. Interior artwork was by Freas mostly, and also John Schoenherr. Analog featured a few ads: for the Science Fiction Book Club, for Edmund Scientific, for Simon and Schuster’s The World of Mathematics, and a PSA about good driving.

[Click the SFBC ad at left, or any of the book covers below, for larger images.]

Campbell’s editorial is at the beginning perhaps less contrarian this time than often: it’s called “It’s Been a Long, Long Time,” and it concerns solid state electronics and how they were revolutionizing the field. All very sound.

He wraps it up, though, by pointing out how radically different solid state electronics was from what came before, and how the paradigm of thinking changed (from frequency based to pulse based — I think what he really meant was from analog to digital), and then kind of suggests that the next revolution of that sort will be psionics. Oh well.

The science article is “Twin-Planet Probe,” by “Lee Correy” (G. Harry Stine). Generally Stine used the name “Correy” for his SF, and indeed “Twin-Planet Probe” is a sort of “non-fact article,” being a report of Martian space probes examining the “twin planets,” Terra and Luna, and determining that Luna was the more “Martian” and thus the better candidate for life.

The Analytical Laboratory reports on November. The first place story was the conclusion to Mack Reynolds’s “Space Pioneer,” followed by stories from H. Beam Piper (“Down Styphon”), John Brunner (“Even Chance”), and Robert Conquest (“A Long Way to Go”) (! — I knew Conquest had done some SF, including the novel A World of Difference, but I didn’t know he had been in Analog).

The Analytical Laboratory reports on November. The first place story was the conclusion to Mack Reynolds’s “Space Pioneer,” followed by stories from H. Beam Piper (“Down Styphon”), John Brunner (“Even Chance”), and Robert Conquest (“A Long Way to Go”) (! — I knew Conquest had done some SF, including the novel A World of Difference, but I didn’t know he had been in Analog).

The only name I recognized in the lettercol, Brass Tacks, was that of John T. Phillifent. But the letter I found most interesting was from Scott Wyatt, not so much because of Wyatt’s contribution, but because of the subject matter and Campbell’s response. Wyatt wrote to complain that “Down Styphon,” from the November 1965 Analog, had been previously published as part of the Ace novel Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen. Campbell’s response gives an explanation of the circumstances of Piper’s suicide.

He writes:

The mixup occurred due to two closely timed deaths. Analog bought “Down Styphon” — it was written for us, as a sequel to “Gunpowder God” — from H. Beam Piper, through Piper’s agent Ken White. Unfortunately, Ken White died suddenly, leaving all his affairs in a chaotic mess. (It was this, in part, that put Piper in such a financial jam, and caused the acute depression that led to his suicide.) No one seems to have known just what the status of affairs at Ken White’s office was, and for months manuscripts, letters, checks, and everything else were stalled on dead center.

Then Piper died.

Another “author’s agent” took over responsibility for Piper’s literary estate — but without adequate knowledge of the situation with respect to legal right, et cetera, of many of Piper’s stories.

Our agreement with Ken White was, as usual, that we would have first publication of “Down Styphon”. The new agency, because of the chaos White’s sudden and completely unexpected death caused, didn’t know that, and sold book rights to Ace Books.

Result: a complete confusion of rights and stories for which no one can be blamed.

This all seems to jibe with the well-known story of Piper’s death, but it’s interesting to read this brief account relatively soon after the event.

This all seems to jibe with the well-known story of Piper’s death, but it’s interesting to read this brief account relatively soon after the event.

P. Schuyler Miller’s Reference Library opens by reviewing Galactic Diplomat, by Keith Laumer; and Flandry of Terra, by Poul Anderson; as a sort of compare and contrast of two very different interstellar diplomats. He comes down decidedly on the side of Flandry.

He reports briefly on the 1965 Hugo Awards, and notes the upcoming Nebulas (which would be the first), and with approval says “And for good measure, the SFWA will edit an anthology of the best science fiction — no fantasy — made up of the winners plus other outstanding stories.” I was struck by the “no fantasy” interjection — with Miller’s obvious approval. Was that really SFWA’s intention then? And if so, how long did it last?

Miller also reviews Anderson’s The Star Fox, mostly but not entirely positively. Also, The Worlds of Robert F. Young, in which he places Young as a “slick” writer (he had published a couple of pieces in The Saturday Evening Post), not entirely in an approving manner, though Miller allows that he does actually rather like some of the stories.

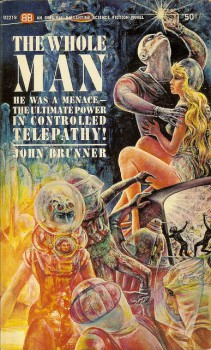

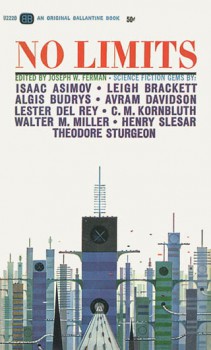

He reviews Brunner’s The Whole Man, very positively, calling it far and away Brunner’s best to date. (As had most reviewers, of course.) He gives a somewhat puzzled review of the Belmont anthology Masters of Science Fiction, wondering why no editor is given, but praising it as a pretty good if not great collection of fairly obscure stories. And he gives a positive review to Joseph Ferman’s (presumably the actual editor was Edward) No Limits, a collection of stories from F&SF and Venture.

He reviews Brunner’s The Whole Man, very positively, calling it far and away Brunner’s best to date. (As had most reviewers, of course.) He gives a somewhat puzzled review of the Belmont anthology Masters of Science Fiction, wondering why no editor is given, but praising it as a pretty good if not great collection of fairly obscure stories. And he gives a positive review to Joseph Ferman’s (presumably the actual editor was Edward) No Limits, a collection of stories from F&SF and Venture.

The stories are:

- “The Searcher”, by James H. Schmitz (24,000 words)

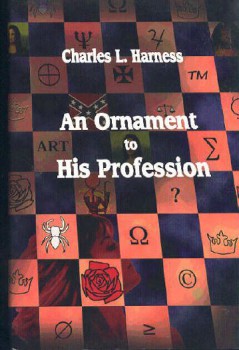

- “An Ornament to His Profession”, by Charles Harness (15,000 words)

- “The Switcheroo Revisited”, by Mack Reynolds (8,000 words)

- “Minds Meet”, by Paul Ash (3,900 words)

“The Searcher” is a Hub story from Schmitz, but it does not feature either of his most famous heroines, Telzey Amberdon and Trigger Argee. Instead the heroine is Danestar Gems, from the Kyth Interstellar Detective Agency. Danestar is an expert in miniature gadgetry. Unfortunately, this is all we really get to know of her, besides that she is “a long-waisted, lithe, beautiful girl”.

That’s a weakness in the story — Danestar is really a cipher, unlike Telzey and Trigger, who do acquire real characters over there multiple appearances. The other weakness is not uncommon to Schmitz’s stories — the resolution depends to too great an extent on basically luck, or rather the unusual powers depicted taking on whatever aspect the plot requires.

The story is about an energy creature from a dust cloud called the Pit which has come to Mezmiali, a planet just two light years from the edge of the cloud. The creature is in search of an alien instrument it needs. As it happens, Danestar and her partner are investigating a smuggling group that just happens to be trying to smuggle that particular instrument to private buyers. The energy creature can simply absorb humans, unless they are Danestar and her partner, in which case there will only be close calls. The story begins as a detective story about Danestar foiling the smugglers, but the last half or so is a chase between her and her partner and the energy creature, until she magically figures out how to zap it.

The story is about an energy creature from a dust cloud called the Pit which has come to Mezmiali, a planet just two light years from the edge of the cloud. The creature is in search of an alien instrument it needs. As it happens, Danestar and her partner are investigating a smuggling group that just happens to be trying to smuggle that particular instrument to private buyers. The energy creature can simply absorb humans, unless they are Danestar and her partner, in which case there will only be close calls. The story begins as a detective story about Danestar foiling the smugglers, but the last half or so is a chase between her and her partner and the energy creature, until she magically figures out how to zap it.

I thought it one of Schmitz’s weaker pieces, though others seem to like it a lot.

“An Ornament to His Profession” was Charles Harness’s return to the field after a 12 year absence. As most folks here probably know, Harness was a patent lawyer, and he had stopped writing to concentrate on his day job (I believe on the birth of his daughter). This particular return lasted only two years (in publishing terms) — he would return more or less permanently in the late ’70s, after his retirement, I believe.

This is one of Harness’s most famous stories — it was a Nebula and Hugo nominee for Best Novelette, and it was the title story of NESFA Press’s complete collection of his short fiction. (Well, complete except for those stories published after it appeared.) And it pretty much deserves its fame.

This is one of Harness’s most famous stories — it was a Nebula and Hugo nominee for Best Novelette, and it was the title story of NESFA Press’s complete collection of his short fiction. (Well, complete except for those stories published after it appeared.) And it pretty much deserves its fame.

It’s about Conrad Patrick, a patent lawyer for a chemical company (a description that applied to Harness, I understand), who has a problem: the process for making the new chemical they are about to introduce was “invented” by one of their employees as a prank.

And the only reason it works, apparently, is that the ambitious man in charge of turning the process into a production line made a deal with the devil — a deal for which he wants Patrick’s help with the contract. Patrick is also still mourning the death of his wife and young daughter in an accident. And he’s rather bitter about his career.

It’s Patrick’s personal issues that make the otherwise simply one-jokish clever central idea actually work, but work it does — it’s a moving story, and unusually for Campbell’s Analog, the ending is rather dark in tone, and the story is, by my lights, definitely a fantasy. (I mean, deals with the devil!)

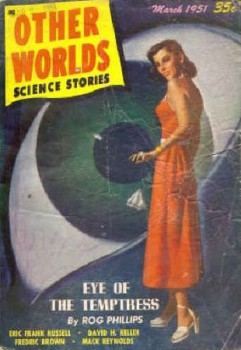

Mack Reynolds’s “The Switcheroo Revisited” is a comic story with a somewhat dark ending too. It’s about a Russian who misinterprets an SF story as a scientific article. (The story is apparently “The Switcheroo”, by Reynolds with Fredric Brown, from the March 1951 Other Worlds.)

Mack Reynolds’s “The Switcheroo Revisited” is a comic story with a somewhat dark ending too. It’s about a Russian who misinterprets an SF story as a scientific article. (The story is apparently “The Switcheroo”, by Reynolds with Fredric Brown, from the March 1951 Other Worlds.)

The Russian agent is given the task of going to the US and meeting the hero of this story, Tarkington Perkins, in order to obtain his invention for the USSR. When the Americans figure this out, they set up a fake household with an agent impersonating Tarkington Perkins. All fairly amusing, but Reynolds extrapolated the end result of these machinations in an also amusing — but quite blackly amusing — way.

And finally Paul Ash’s “Minds Meet” is Pauline Ashwell’s fourth story for Astounding/Analog, her second as by “Paul Ash”. (I understand that she had published a story in a publication called Yankee Science Fiction, as by “Paul Ashwell”, more than a decade before her first appearance in Astounding, which was in 1958.)

It’s another pretty good story. A human base on an alien planet is having a party as they close up shop — after seven frustrating and only partly successful years working on setting up a common base of translation with the aliens. Slightly drunk, one of the scientists accidently contacts his opposite number among the aliens, and says some things deemed offensive. The alien responds in a supposedly offensive fashion as well — turns out they’ve been partying too.

The upshot is that by communicating with fewer inhibitions, they make as much progress in a short time as they had in the past seven years, more or less. The setup may be a bit strained and exaggerated, but I thought the point well made.

The upshot is that by communicating with fewer inhibitions, they make as much progress in a short time as they had in the past seven years, more or less. The setup may be a bit strained and exaggerated, but I thought the point well made.

I had thought, in reviewing these three magazines at the cusp of 1966, with the New Wave just breaking out, to make some comment about how it affected each magazine. As earlier noted, a couple of stories in the December 1965 Galaxy were basically New Wave, but none in the January 1966 F&SF.

I didn’t expect to see any in any Campbell-edited issue of Analog, and probably none here really qualify, but in all honesty an argument could be made for “An Ornament to His Profession” … though I think Harness was always just weird in his own way. (But note the outsize admiration professed by for example Brian Aldiss for Harness’s brilliant strange early novella “The Rose”.)

[…] of science fiction and fantasy digest magazines from the mid-20th Century. The first three were the February 1966 Analog, the December 1965 Galaxy, and the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & […]

[…] of science fiction and fantasy digest magazines from the mid-20th Century. The first four were the February 1966 Analog, the December 1965 Galaxy, the January 1966 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, […]