John Devil and the World of Paul Feval

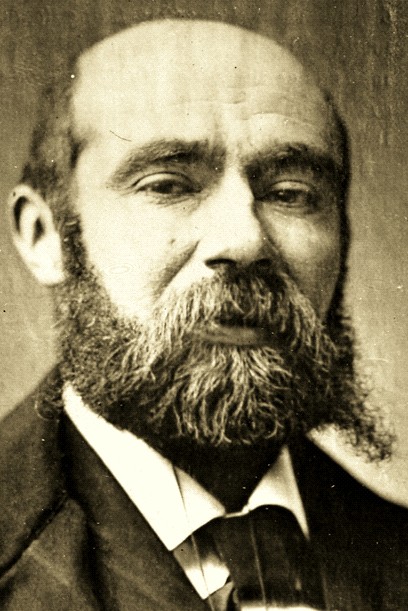

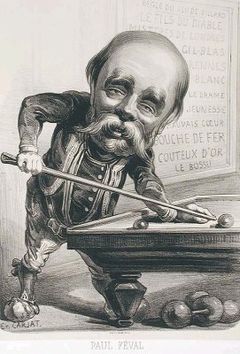

John Devil was my first introduction to the works of Paul Feval. At nearly 650 pages, it is a massive tome and without the efforts of scholar and translator Brian Stapleford and editor and publisher Jean-Marc Lofficier and his Black Coat Press imprint (named after Feval’s long-running crime series) it is likely few readers outside of France would ever have discovered the work or any others by its author.

John Devil was my first introduction to the works of Paul Feval. At nearly 650 pages, it is a massive tome and without the efforts of scholar and translator Brian Stapleford and editor and publisher Jean-Marc Lofficier and his Black Coat Press imprint (named after Feval’s long-running crime series) it is likely few readers outside of France would ever have discovered the work or any others by its author.

John Devil is noteworthy as a book of firsts. Written in 1861, Jean Diable is believed to be the first novel detailing a police detective hunting down a master criminal. That is not to suggest that John Devil offers anything approaching standard fare for the genre. The novel was originally published as a serial and consequently is heavily padded with literally dozens of characters, dual identities, and countless interconnecting plotlines. While certainly not as difficult a read as the seminal penny dreadful, Varney the Vampire, John Devil is nonetheless a far cry from Feval’s later more polished works.

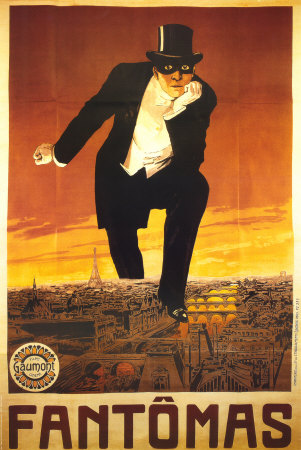

John Devil is the code name for a long line of brilliant, but savage criminal masterminds. When one John Devil is killed or imprisoned, another comes along to take his place. The character reads like a dry run for both Dr. Mabuse and Fantomas. Feval’s emphasis on contrasting the lives of the aristocracy with that of the common working class very much put me in mind of Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain’s Fantomas series in particular. The similarity is emphasized by the cover art for the US edition of John Devil from Black Coat Press which deliberately recalls the famous artwork for the original Fantomas.

While Fantomas is a madman and anarchist whose control of the criminal underworld is based solely in terror, John Devil is rooted deeply in Freemason conspiracy theories. Feval presents a world in which no one is who they claim to be, loyalties are constantly divided, and an undercurrent of paranoia exists around the belief that Freemasons are the puppet masters controlling not only the criminal element, but also engineering political and military maneuvers.

While Fantomas is a madman and anarchist whose control of the criminal underworld is based solely in terror, John Devil is rooted deeply in Freemason conspiracy theories. Feval presents a world in which no one is who they claim to be, loyalties are constantly divided, and an undercurrent of paranoia exists around the belief that Freemasons are the puppet masters controlling not only the criminal element, but also engineering political and military maneuvers.

Gregory Temple of Scotland Yard is the character that will most interest fans of detective fiction. Temple plays a pivotal role in the proceedings, but sadly is not the central character. Had Feval done so, it is likely that John Devil would have remained in print all over the world as the acclaimed first true detective novel. As it is, Temple is a brilliant detective relying on deductive reasoning and clever disguises to track down an even more brilliant criminal. However, the serial nature of the book means that Temple’s plotline frequently disappears for whole chapters at a time while Feval broadens the story’s scope to include as many characters as possible. Stableford’s lengthy footnotes and essays (including a multi-page scorecard of the various characters) are essential for modern readers to not lose their way or their patience in reading a work that while equal in ambition to contemporaneous work by Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas is severely lacking their gravitas.

Unsurprisingly, it matters less who John Devil actually is and how he commits his fantastic crimes as it does that the reader accept Feval’s conspiracy theory of a theosophical cabal controlling much of Europe and the New World behind the guise of politicians, kings, dictators, and crime lords. Much like Yellow Peril fiction or Cold War espionage thrillers, accepting the credibility of the threat is essential to appreciating the work. Readers who are unable to step outside of their own times will never enjoy such fiction because it runs contrary to contemporary thinking on politics or other nations and their cultures.

Unsurprisingly, it matters less who John Devil actually is and how he commits his fantastic crimes as it does that the reader accept Feval’s conspiracy theory of a theosophical cabal controlling much of Europe and the New World behind the guise of politicians, kings, dictators, and crime lords. Much like Yellow Peril fiction or Cold War espionage thrillers, accepting the credibility of the threat is essential to appreciating the work. Readers who are unable to step outside of their own times will never enjoy such fiction because it runs contrary to contemporary thinking on politics or other nations and their cultures.

By the time he launched the successful Black Coats crime series, Feval decided to connect his earlier crime fiction into a loose continuity allowing readers to accept his works as a pseudo-historical chronicle of France during and immediately following the Napoleonic era. While Brian Stableford’s translation of the final novel in The Black Coats series later this year will see the entire sequence available in English translations for the first time, John Devil remains the only one of Feval’s four earlier crime novels to currently be in print for English-speaking readers to enjoy.

Feval’s serial also spawned a long-running pulp magazine of the same name that Feval edited with Emile Gaboriau. The latter was influenced by Gregory Temple to create the Monsieur Lecoq series which influenced both Edgar Allan Poe’s Monsieur Dupin stories and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series. For this reason alone, serious students of detective fiction should have John Devil on their bookshelf as it is an essential step in the development of a genre that is still thriving 150 years on.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). A sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu is due for publication in December 2011. Also forthcoming is a collection of short stories featuring an original Edwardian detective, The Occult Case Book of Shankar Hardwicke and an original hardboiled detective novel, Lawhead. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com