An Interview With Claude Lalumière, Part Two

Here’s Part Two of my interview with writer, critic, and editor Claude Lalumière. You can find Part One here. This time around, we discuss Claude’s influences, his work as an anthologist, his criticism, and his process as a writer. My great thanks to Claude for his generosity, thoughtfulness, and candor.

Here’s Part Two of my interview with writer, critic, and editor Claude Lalumière. You can find Part One here. This time around, we discuss Claude’s influences, his work as an anthologist, his criticism, and his process as a writer. My great thanks to Claude for his generosity, thoughtfulness, and candor.

An Interview with Claude Lalumière, Part Two

Conducted and Transcribed by Matthew David Surridge

Your fiction shows the powerful influence of a number of different writers, and the fusion of those particular writers creates something strong and unusual. Could you write a bit about how you first encountered the work of people like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, J.G. Ballard, Ursula K. Le Guin, Lucius Shepard, Rachel Pollack, and Paul Di Filippo, and what those writers came to mean to you?

This is a question requiring an epic-length answer.

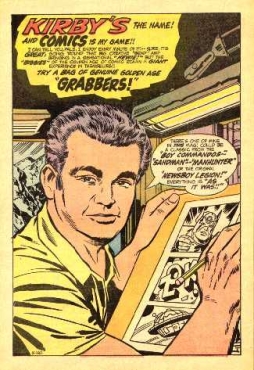

Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby is God. And I say that as an unshakeable atheist. For those who might not know, Kirby is — I say “is” rather than “was,” even though he died in 1994, because his influence is undying — the “King of comics”: an insanely imaginative genius whose creativity knew no bounds and whose output was superhuman in both quantity and quality. His imagination still looms large over most American adventure comics. When I was a boy, Kirby and Kirby’s creations colonized my consciousness. The older I get, the more profoundly I appreciate Kirby’s accomplishments as cartoonist, writer, and creator.

Kirby’s Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth! #29 (“Mighty One”) is possibly the greatest single issue of a comics series ever. It taught me how myth works, a lesson that has been invaluable in my own writing. When I think of myth, the first thing that always comes to mind is this story. I remember rereading it obsessively, again and again and again. It’s also the greatest Superman story ever told.

To continue with this notion of Kirby and myth — his work and influence also loom very large over what I do with Lost Myths. Without Kirby, Lost Myths would not be what it is.

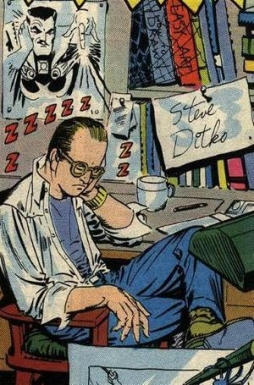

Steve Ditko

Steve Ditko

Steve Ditko — best known as the co-creator of Spider-Man — is adept at designing visually arresting and evocatively iconic costumed characters. He possesses that combination of qualities a great cartoonist (or artist in any field) needs: a visionary approach to his craft and a distinctive, unique voice. But his worldview is, to say the least, toxic. Nevertheless, the characters he came up with have a knack for crawling under my skin, and he’s a killer storyteller. I keep coming back to Ditko. Every time I think that well is dry, something up surges from my subconscious. I think it’s the problem-solving part of my mind at work, trying to reconcile Ditko’s consummate and visionary artistry with his noxious Objectivism. As with Kirby, I was exposed to Ditko at a young age, and my appreciation of his craft keeps growing with age.

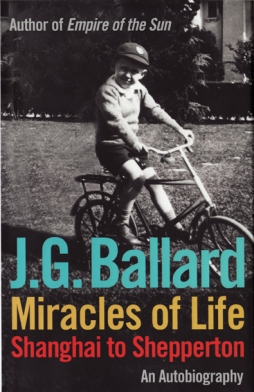

J.G. Ballard

J.G. Ballard

Ballard is my favourite writer. I started to read Ballard in the late 1980s, in my early twenties, and the impact on my imagination was one of paradigmatic transformation. The first book of his I read was the collection The Terminal Beach, which was almost too much for me to take in. I remember it causing me some sort of information overload. There was so much in there that spoke to me and commanded my full attention. I couldn’t just read him casually — it would be like trying to listen to Impulse!-era Coltrane casually — no, this level of artistry demands my full attention. The first novel of his I read was The Drowned World, and I thought it was simply the greatest piece of writing I’d ever encountered — until I got to Crash, which remains, for me, an unsurpassable achievement. Ballard is one of those artists whose work permeates most of what I do, but I can point to three stories that are more explicitly Ballardian: “Being Here” (from the anthology Tesseracts Nine); “This Is the Ice Age” (in Objects of Worship); and, most of all, “Vermilion Dreams: The Complete Works of Bram Jameson” (in Tesseracts 14), an epic metafictional homage to Ballard that I composed in a mad flurry immediately after reading his memoir, Miracles of Life, and learning that he was dying of cancer, a piece of news that devastated me, even though I had never, and have never, met him, and, now that he’s dead, never will. Writing that story was my way of coping with imminent loss.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guin

I’m not sure anymore what was my first exposure to Le Guin’s work. In the mid-1980s, I started to seriously explore the New Wave-era writers, one of my favourite eras in SF, and she was part of that package. I will admit to generally not being fully won over by those works most people consider her classics. That said, two of her books hit me deeply where I live and continue to reverberate, decades later. Anyone who knows me well knows that I am driven by a utopian yearning that colours all my experiences, and I have yet to encounter a book that better expresses that emotion than Always Coming Home, a book that is as endlessly fascinating for its content as it is for its formal bravado. A significant portion of my writing is an attempt to recreate the effect that Always Coming Home had on me. And then there’s Orsinian Tales, that subtle and gorgeous mosaic of stories about a fictional European country. My stories about the fictional European city-state Venera, although very different in tone and style to Le Guin’s stories of Orsinia, are their descendants.

Lucius Shepard

I’ve tried to pastiche Lucius Shepard, to learn how to write those gorgeous long sentences that he composes, but I failed miserably. But there is one plot-structure thing that he does that’s always fascinated me and that I tend to do also — because it works so well; because it obviously speaks to me, as it fascinates me so much; and because I want to try to get to the heart of why that plot trick strikes so a profound chord. I’m not going to say what it is though. I need to keep some secrets! I first discovered Shepard’s writing with the Ace SF Specials of the 1980s. I thought his Green Eyes was the best book of a strong lot of novels picked by the late, great Terry Carr, but it’s when I started reading Shepard’s short fiction, with the American trade paperback release The Jaguar Hunter, that I was completely floored by the breadth and depth of his talent.

Rachel Pollack

Rachel Pollack

The semi-title story to my collection Objects of Worship, “The Object of Worship,” is explicitly an attempt at working through my problematic and complex reaction to Rachel Pollack’s Unquenchable Fire, one of the finest works of imaginative fiction ever created and one that has never stopped living within me. I first read it when the UK massmarket paperback reached Canada in 1989. The story was written fifteen or sixteen years later. I still think about that book all the time.

Paul Di Filippo

As I’ve mentioned a few times at this point, I’m a utopian. Well, my pal and fellow dreamer Paul Di Filippo wrote the single greatest utopian alternate-history story ever: “Campbell’s World.” On top of being the most sense-of-wondrous little gem anyone can imagine, on top of packing a powerful emotional punch, on top of being written with superlative wry elegance, that story is basically a manifesto on why we need to continue to write imaginative fiction. Why imaginative fiction is necessary to our collective good. Every single SF class, hell, every writing class — period — should teach that story. The title of the Di Filippo collection it’s found in: Lost Pages. And then in 1999 I found myself writing a story — “Bestial Acts,” a tale driven by utopian longing — about a reality-hopping bookshop. I wanted to honour Paul by naming the bookshop after his book, which, really, is a great name for a bookstore. Little did I know that Lost Pages would become so central to my writing project and that one day I would write a whole book — a mosaic novella — centered on the conceit of that bookshop: The Door to Lost Pages. Paul is such a class act that he even wrote the introduction for it.

What other writers do you find to be of equal significance to you, your fiction, and The Door to Lost Pages?

There are two books that I feel need bringing up immediately, and these are not books that influenced me (at least, not at first) but rather books that display an astonishing synchronicity with The Door to Lost Pages.

Even though The Door to Lost Pages is my second published book, it’s actually assembled for the most part from some of my earliest writings. The stories that now constitute chapters 1-3 were first written in 1999, although they would only see print in 2002 and 2003. But, between their initial composition and their publication, two books came out that, each in their own way, were doing something quite similar to what I was attempting. In fact, it would not seem inaccurate to say that my Lost Pages stories are an attempt at a collage of those two books, which are quite different from each other: The Perseids and Other Stories (2000), by Robert Charles Wilson, and City of Saints & Madmen (2002), by Jeff VanderMeer — except that I had not yet read a word of either work before writing about half of my Lost Pages cycle. My heart sank when I encountered these books — “Oh no, I’ve been trumped!” — and I ended up having trouble re-entering that world as a result, but I eventually decided to soldier on anyway and finish the cycle. I wrote one more episode in 2003, and then two more in 2005. After the book was accepted last year, I wrote the prologue and some incidental linking material — in addition to doing quite a bit of rewriting and cutting.

Even though The Door to Lost Pages is my second published book, it’s actually assembled for the most part from some of my earliest writings. The stories that now constitute chapters 1-3 were first written in 1999, although they would only see print in 2002 and 2003. But, between their initial composition and their publication, two books came out that, each in their own way, were doing something quite similar to what I was attempting. In fact, it would not seem inaccurate to say that my Lost Pages stories are an attempt at a collage of those two books, which are quite different from each other: The Perseids and Other Stories (2000), by Robert Charles Wilson, and City of Saints & Madmen (2002), by Jeff VanderMeer — except that I had not yet read a word of either work before writing about half of my Lost Pages cycle. My heart sank when I encountered these books — “Oh no, I’ve been trumped!” — and I ended up having trouble re-entering that world as a result, but I eventually decided to soldier on anyway and finish the cycle. I wrote one more episode in 2003, and then two more in 2005. After the book was accepted last year, I wrote the prologue and some incidental linking material — in addition to doing quite a bit of rewriting and cutting.

But back to Wilson’s The Perseids and Other Stories and VanderMeer’s City of Saints & Madmen: I also had another reaction to those two books. I thought they were fucking brilliant. Did they influence the later chapters of my story cycle? I’m not sure, but I am certain that I love both of those books.

But back to Wilson’s The Perseids and Other Stories and VanderMeer’s City of Saints & Madmen: I also had another reaction to those two books. I thought they were fucking brilliant. Did they influence the later chapters of my story cycle? I’m not sure, but I am certain that I love both of those books.

And, yes, there are other writers that are important to me as a writer. To name only a few:

I mostly learned the art of narrative structure from carefully studying Robert Silverberg’s astonishing body of short fiction. His work has generally had a huge impact on me, I also learned from him the importance of emotional intensity, and how to try to achieve it. I’ve read more of Silverberg’s fiction than of any other writer’s.

From Jonathan Carroll, I learned the importance of portraying deeply felt relationships and, especially in his early work, the art of allusion and the power of ambiguity.

Philip José Farmer taught me the pleasure of literary collage, marrying pulp excitement with literary ambition. He also taught me that it’s more worthwhile and rewarding to strive constantly to write things a little beyond one’s capacities, to stretch one’s artistic muscles, to never be complacent. Better to try and fail, as he sometimes did, than to be complacent and boring. I don’t think I’m anywhere as brave as he was, but I try to keep his courage in mind when I write. Also, Farmer knew how to show his readers a good time, to entertain them while also trying to do whatever else the story at hand calls for. And that’s a very important lesson.

Jim Thompson, the greatest noir writer and the greatest of American novelists, taught me to never flinch in the face of the darkness of my characters and my ideas.

Jim Thompson, the greatest noir writer and the greatest of American novelists, taught me to never flinch in the face of the darkness of my characters and my ideas.

Roger Zelazny played with myth in a way that resonated powerfully with me in my late teens and early twenties. But I must admit that I spent much of my formative years as a writer getting rid of the traces of his stylistic quirks in my writing, which I found myself aping without narrative justification.

From Theodore Sturgeon, I learned how to have empathy for my characters, all the while staying merciless toward them (writers should never show mercy to their characters, especially to those characters who may resemble the writers themselves).

R.A. Lafferty never ceases to amaze me. His work is always bubbling under the surface when I write, subtly influencing everything I do. What I learned from Lafferty is somewhat ineffable, as his own work usually is.

The writers published in Interzone during David Pringle’s tenure had a huge impact on my imagination. There was the writing community I aspired to belong to: Garry Kilworth, Geoff Ryman, Richard Calder, Ian Watson, Scott Bradfield, Kim Newman, Eugene Byrne, Michael Blumlein, Brian Stableford.

Do you find your editing work reflects or affects your own fiction? What, if anything, have you learned from editing?

Editing anthologies is combining two pleasures. One, I love anthologies and don’t really understand why they’re not more popular, why they don’t outsell everything else. So it’s my stab at trying to put together a killer assemblage of stories. Two, working with the writers, because I’m a very hands-on editor, is one more way for me to hone my thinking about the craft of short fiction. In a perfect world, I’d be editing two anthologies every year.

Editing anthologies is combining two pleasures. One, I love anthologies and don’t really understand why they’re not more popular, why they don’t outsell everything else. So it’s my stab at trying to put together a killer assemblage of stories. Two, working with the writers, because I’m a very hands-on editor, is one more way for me to hone my thinking about the craft of short fiction. In a perfect world, I’d be editing two anthologies every year.

But to answer your question more directly: although editing anthologies is a tool that can help me hone both my craft and my thinking, I can’t say that I’ve learned any specific thing as a writer from editing. It’s just part of the process of thinking about short fiction.

As an editor, what do you strive for? By that I mean: What do you look for in an individual story, beyond simply good writing, and how do you go about building a collection of stories?

Of course, the ideal is to get perfect, visionary stories that need no editing. That rarely happens. I’m not averse to getting my hands dirty and plunging deep into a story with a writer to get to the best possible version of the text.

What I look for the most is voice. I want to be seduced. Seduce me, and I’m putty in the face of your words. The voice has to grab me, make me want to unpeel the layers of the story to come.

If I have to choose between a “good” story that needs no editing but will never be great and a potentially great story that might need to go through a few drafts before I send in the manuscript to the publisher, I’ll choose the diamond in the rough over the slick but only adequate tale. I don’t mind the extra work if the prize is helping a spectacular story to live up to its potential, to work with a colleague on a text that might really wow readers. To work with a colleague on the ongoing collective effort of bettering the craft of short fiction.

If I have to choose between a “good” story that needs no editing but will never be great and a potentially great story that might need to go through a few drafts before I send in the manuscript to the publisher, I’ll choose the diamond in the rough over the slick but only adequate tale. I don’t mind the extra work if the prize is helping a spectacular story to live up to its potential, to work with a colleague on a text that might really wow readers. To work with a colleague on the ongoing collective effort of bettering the craft of short fiction.

Of course, as you build a book, sometimes it’s not only about picking the best stories. It’s also about balance. Once, I received two equally good stories that were almost identical. There was no plagiarism. The setting and characters were not the same, but the tropes, the story arc, the metaphors, even the matter of the tale were just about identical. And the story they were each telling in their own idiosyncratic way was rather unusual, but there was a synergy thing happening. Clearly, that story needed to be told at that time, and they’d both stumbled onto it. I was thus compelled to have some form of that story in that book, but I couldn’t use both: they were too similar. It’s hard to reject a story when it’s for a reason of that nature. Irony: I’ve since become very good friends with the writer whose story I rejected, but I’ve no contact whatsoever with the one whose story I published.

You review fantastika and comics for The Montreal Gazette, Montreal’s daily English-language newspaper, and have written reviews for a number of other places — including comics reviews for Black Gate. What do you think writing criticism does for you as a writer, and how do you approach the task of criticism? I know you try to provide context in your reviews, for example; what else is it important for you to do in a piece of criticism?

Because I usually write reviews for a general audience, it’s important to me to try to contextualize both the work at hand and the author. There’s a pedagogical element that comes into play. The other thing that is important to me is to try to make it clear that the review is subjective. I don’t believe in objectivity. Objectivity is a lie used by the status quo, or by the dominant, to silence opposing, non-dominant views. I try to make my subjectivity explicit.

Because I usually write reviews for a general audience, it’s important to me to try to contextualize both the work at hand and the author. There’s a pedagogical element that comes into play. The other thing that is important to me is to try to make it clear that the review is subjective. I don’t believe in objectivity. Objectivity is a lie used by the status quo, or by the dominant, to silence opposing, non-dominant views. I try to make my subjectivity explicit.

As a critic, what principles are important to you? Generally, how do you approach a text?

To reiterate the above: explicit subjectivity is a paramount virtue in criticism. Also, of course, I try to approach the text being reviewed within the body of the author’s work and within the context of the genre(s) and subgenre(s) being explored. But ultimately it’s a gut reaction to the esthetics of the work: does it work or not? Sometimes, I backtrack from my gut reaction, to try to figure out why I had a strong pro or con reaction. Sometimes, that process makes me re-evaluate the work in the process of writing the review. Sometimes, my analysis will lead me to a different conclusion than my gut, and in those cases, if I don’t have enough wordage to allow for a nuanced review, I will generally err on the side of the most generous of the two interpretations.

I rarely write reviews that are entirely negative or positive. I see criticism as contributing to the dialogue about craft and the state of the art. So my praise is often sprinkled with a bit of nitpicking, and my pans often also point out something worthy in the text being examined.

More specifically: I know that you’re very critical of a tendency to conservatism, both artistic and political, in fantasy fiction. How do you think this conservatism affects the quality of writing in fantasy?

Art is a quest. Art questions. Art is restless. Art pokes and prods. Art shit-disturbs. Art is disquieting. Art is ambiguous. Art is startling. Art is new. Art is dreaming the impossible dream. Art is beautiful, but beauty is a rare thing. Art yearns. “Art” that tries to comfort, to support the status quo is, as far as I’m concerned, anti-art. Art is not propaganda. If you already know the answers, or think you do, write an essay, not fiction. Fiction is for exploration, for getting us to think and feel beyond what we already know, for both writer and reader. So, by definition, art cannot be conservative. Anti-art is not good art, not good writing.

Art is a quest. Art questions. Art is restless. Art pokes and prods. Art shit-disturbs. Art is disquieting. Art is ambiguous. Art is startling. Art is new. Art is dreaming the impossible dream. Art is beautiful, but beauty is a rare thing. Art yearns. “Art” that tries to comfort, to support the status quo is, as far as I’m concerned, anti-art. Art is not propaganda. If you already know the answers, or think you do, write an essay, not fiction. Fiction is for exploration, for getting us to think and feel beyond what we already know, for both writer and reader. So, by definition, art cannot be conservative. Anti-art is not good art, not good writing.

Could you talk a bit about your drafting and editing process?

Well, my early stories tended to go through many, many drafts, often with quite radical rewrites. Now, because with experience I tend to make better first guesses as to what a story needs, I mostly do cosmetic edits only anymore.

Speaking of solely fiction per se (the Lost Myths texts undergo a different process): what’s the hardest for me, though, remains the first draft. It’s often an emotionally and even physically difficult process. But, once I have the raw material of the first draft, I can be merciless with my text, and I enjoy editing and rewriting much more than composition. But, as I said, I now do much less rewriting than I used to.

For Lost Myths, it’s the other way around: composition is a delight, a fun ride through everything that I love about imagination and myth. Compared to that, the process of editing feels so mundane and tedious, and I get impatient with it, in a way I never do editing my regular fiction.

I know the form of short fiction is of great interest to you. The Door to Lost Pages, as linked short stories, could certainly be viewed as your longest work, but you’re mostly fascinated by short fiction. Could you talk a bit about why that is? What in the short form draws you?

I know the form of short fiction is of great interest to you. The Door to Lost Pages, as linked short stories, could certainly be viewed as your longest work, but you’re mostly fascinated by short fiction. Could you talk a bit about why that is? What in the short form draws you?

Honestly, I don’t really know. When I first set out to write, I thought I would write novels. I didn’t know yet that I was a short-fiction writer. Certainly, I’d always loved short fiction as a reader. I know that, generally speaking, I prefer to discover new writers by their short fiction, but not all writers are equally adept at both forms, so that can backfire as a reading strategy. The novel and the short story are not quite the same art form. They’re certainly related, but they’re not the same.

Many of my favourite writers have significant bodies of work in short fiction: Silverberg, Ballard, Di Filippo, Shepard, Sturgeon, Lafferty. And, as a reader, I’ve always loved anthologies.

Without really meaning to, I wound up writing short fiction and getting completely obsessed with the craft of short fiction. I’m a compulsive problem-solver. Short fiction became a problem for me to solve. How did that stuff work? How could I make it work in a way that I could still make it my own? So I gnawed and gnawed at it. These days, I don’t gnaw quite so much, because I have a better idea of what I’m trying to accomplish and how to do it. That said, there are some aspects of all this that remain ineffable, that are still shrouded in mystery, and my imagination is constantly probing those areas. When I’m lucky, when I manage to attain a receptive state of mind, a story emerges from that process.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

[…] and Ann VanderMeer Chat With Terry Bisson at SF in SF (podcast).Matthew David Surridge interviews Claude Lalumière.News Now posted: on Hub Magazine 138. The award-winning Heroes in Hell series, originally published […]

[…] Matthew David Surridge interviews Claude Lalumière, Part Two. […]

[…] a post to satisfy the Kirby partisans out there (I’m talking to you, Claude Lalumière), but I’m hoping it’ll help you all understand a little better why I feel the way I do […]

[…] a post to satisfy the Kirby partisans out there (I’m talking to you, Claude Lalumière), but I’m hoping it’ll help you all understand a little better why I feel the way I do about […]

[…] the public domain and freely available online) can be seen in Superman. It’s also true (as Claude Lalumiére observed to me when he sold me his copy of the book) that the novel seems to have had as much or […]