James Schmitz’s The Demon Breed: SF as a Test-bed for Living (With Women who Kick Alien Butt)

I’d like to take some time to talk about the impact of simple truths and how perceptions long thought changed need regular revisits so we don’t forget. We become comfortable after tectonic changes occur that alter the landscape, so comfortable we sometimes get caught by surprise when an example of what we believed was long gone springs up before us, not nearly as banished as we’d thought. We forget, most of us.

I’d like to take some time to talk about the impact of simple truths and how perceptions long thought changed need regular revisits so we don’t forget. We become comfortable after tectonic changes occur that alter the landscape, so comfortable we sometimes get caught by surprise when an example of what we believed was long gone springs up before us, not nearly as banished as we’d thought. We forget, most of us.

And yes, this is about science fiction and fantasy. Really.

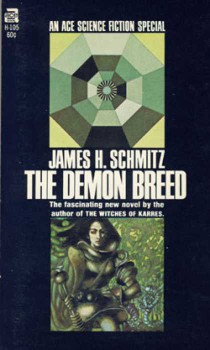

I collected the original run of Terry Carr’s groundbreaking Ace Specials back when they first appeared in the late Sixties. Some truly phenomenal work came out under that imprint, work still published and read today.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, Alexi Panshin’s Rite of Passage, Keith Roberts’ Pavane, The Black Corridor and Warlord of the Air by Michael Moorcock. A number of others that were influential but you have to search for them today, work by Wilson Tucker, Bob Shaw, and Joanna Russ.

Among them was a little novel by a writer not much talked about today except in certain “knowing” circles — James Schmitz. The novel was The Demon Breed and it featured a character that just riveted me.

Tough, smart, capable, a role model for anyone who wanted to grow up competent and self-assured and substantial. Nile Etland.

How I wish Schmitz has written more about this character. I would have followed her adventures as avidly as any other.

[Click on any of the images for larger versions.]

Nile Etland was a special field agent who in the course of this short novel pretty much single-handedly kicked major alien butt. And the remarkable thing about the book, especially for its time, is that she does all this without ever once calling attention to the fact that she’s, you know, a woman.

Schmitz’s major gift was to portray her as a person, whole and fully-realized and utterly unapologetic. It left an indelible impression on my awakening adolescent consciousness that took a while to fully manifest but for which I’ve ever since been thankful.

The trick Schmitz pulled off in this book is one many authors have managed to not get, which is part of what has driven gender discussions in SF and Fantasy, namely that he portrays Nile as a person, wholly and uniquely, completely herself, with no special referents to her gender other than the pronoun. She does what she does because it’s what she does and there’s no special argument in support of her right to do so “because she’s a, you know, woman.”

It may not seem like such a big deal, but when you consider all the other stories that have a strong female protagonist in which the author has found it necessary to explain how a woman got to do this job (and also how she differs from other women and how men resent/admire/respect/reject her because of it), thereby calling attention to the fact that this is unusual in our society and apparently will continue to be unusual in any future or alternate society, then it takes on a bit more significance.

It’s not what Schmitz says but what he didn’t say that makes the trick both impressive and invisible.

It’s not what Schmitz says but what he didn’t say that makes the trick both impressive and invisible.

Heinlein pulled something like this off in Starship Troopers in relation to race issues. But he managed to take time out whenever he put forward a female as a protagonist to stumble because he always felt compelled to explain why she should — and could — do what he had her doing.

One of the signs that progress has occurred is that no one notices a challenge anymore. Issues have been settled, social terms have changed for everyone, and what had once been radical is now normal, even dull, and people no longer question why something is as it is or why it should be. Science fiction about the future has always been one of ways we construct test-beds for living, albeit vicariously, and it is always a bit of a false note to find the same or old arguments still be engaged in the same way in work that deals with otherwise changed milieus.

That said, we still have to address our work to a contemporary audience which may be grappling with these ideas in search of resolution. Showing a world in which things have substantively changed and still making them familiar enough for readers to access easily is a challenge for any writer.

But the pay-off, which every writer would do well to keep in mind, is when someone picks up their work and comes away fundamentally affected, changed, with a new perspective. Preaching doesn’t accomplish that. Something simple — like treating all characters, male or female, whatever orientation or ethnicity, as People first and foremost — can have amazing consequences.

Mark W. Tiedemann is the author of Remains, Realtime, and several other novels. His last article for us was The ABC’s of DNA and Other Thorny Themes: Daryl Gregory’s “The Devil’s Alphabet”