A Review of George MacDonald’s Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women

Warning: Some spoilers ahead

Warning: Some spoilers ahead

Advancing a claim that something is the “first” anything is daring a slippery slope, but saying a book is the “first fantasy” is rather like taking a leap onto a Slip and Slide greased with the gelatin exudate of Cthulhu. George MacDonald’s Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women (1858) could be the first fantasy story … but then, what about Shakespeare’s The Tempest, or Edmund Spencer’s The Faerie Queene, or the Epic of Gilgamesh, or … you get the picture. I happen to agree with our own Matthew David Surridge that Phantastes is likely not the first pure fantasy novel, for the fact that, although it involves another world, it “never quite [leaves] the real world behind.” It’s the stuff of dreams, with a clear path back to earth.

Regardless, Phantastes is without question one of the cornerstones of the genre, and stands poised at the cusp of early works containing fantastic elements, to those that feature fully developed, independent secondary worlds.

The full title of MacDonald’s novel tells us much about the era in which it was written. In the Victorian era fantasy was largely seen as a genre for children. But Phantastes is not nursery room reading. It tells the story of the strange journey of Anodos, who at the portentous age of 21 is a young man ready to cross the border into adulthood. Anodos inherits his father’s estate, including a set of keys to a dark oak cabinet that unlocks a portal to Fairy Land. At the outset of his travels Anodos discovers a carven stone image of a beautiful woman and, breaking into song, returns the lady to life. He’s smitten with her beauty but she does not return his affections.

There is no driving narrative to Phantastes; Anodos wanders about seemingly at random, pining for his lost love. The seemingly arbitrary nature of the tale can be viewed as a metaphor for human existence: How much control do we really have over own lives? We’re often thrust into circumstances beyond our control, and of course, no one determines the era or circumstances into which they are born. Fate and fortune can make it seem like we’re drifting on the current.

Despite its applicability to our own lives and its Bildungsroman elements, Phantastes is pure, unabashed fantasy. The book has a dreamlike quality to it and in fact it’s not clear whether Anodos is dreaming or really in a fantasy; the way in which he enters Fairy Land allows for either interpretation. You won’t find a Tolkienian map in its pages, a backstory, or an historical timeline. We experience Fairy Land as Anodos does, one set piece at a time. At any time we can expect to encounter giants, statues come to life, sentient trees, or Sir Galahad. The writing is very Victorian, which can understandably put some readers off. Here’s a sample of MacDonald’s prose, a description of a wondrous library Anodos encounters in his travels:

Despite its applicability to our own lives and its Bildungsroman elements, Phantastes is pure, unabashed fantasy. The book has a dreamlike quality to it and in fact it’s not clear whether Anodos is dreaming or really in a fantasy; the way in which he enters Fairy Land allows for either interpretation. You won’t find a Tolkienian map in its pages, a backstory, or an historical timeline. We experience Fairy Land as Anodos does, one set piece at a time. At any time we can expect to encounter giants, statues come to life, sentient trees, or Sir Galahad. The writing is very Victorian, which can understandably put some readers off. Here’s a sample of MacDonald’s prose, a description of a wondrous library Anodos encounters in his travels:

And now I will say no more about these wondrous volumes; though I could tell many a tale out of them, and could, perhaps, vaguely represent some entrancing thoughts of a deeper kind which I found within them. From many a sultry noon till twilight, did I sit in that grand hall, buried and risen again in these old books. And I trust I have carried away in my soul some of the exhalations of their undying leaves.

Overall I enjoyed Phantastes, though it does present some difficulties, especially for those who come to it grounded with the expectations of a modern novel. Some of Anodos’ excursions seem maddeningly arbitrary, and at other times MacDonald luxuriates too long in description. But other episodes remain burned into my memory. Anodos’ travels in the halls of a black and white marble palace amid living statues is exquisitely otherworldly. The tale takes a rousing heroic turn when he joins a pair of brothers to rid Fairy Land of a trio of marauding giants. And Anodos’ encounter with an old woman, and his fateful decision to leave the safe confines of her hut and pass through the door of “the Timeless,” resonates like the archetypal son leaving his doting mother. She knows she must let him go but frets at the awful travails that await.

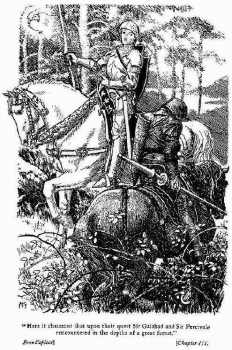

During his travels Anodos acquires a shadow, which dogs his heels as the visible representation of his own guilt. He suffers many stumbles along the way but is eventually able to shed his egocentricity and fierce early jealousies and achieve self-realization. When the beautiful stone woman finds love in the arms of a knight, Anodos recognizes the man as his moral superior and the proper companion for his beloved queen. It’s another sign of the evolution of his mature self. Says Anodos: “This,” I said to myself, “is a true man. I will serve him, and give him all worship, seeing him the embodiment of what I would fain become.”

Phantastes is not exactly anti-heroic but it’s also not heroic fantasy. Anodos briefly becomes a reluctant hero when he takes up the sword to save Fairy Land from the cruel depravations of a trio of giants. But his victory is tempered with the realization that better men than he have died in the cause. His newfound celebrity galls him; he leaves his fine armor and steed. The life of a knight is not for him, and he realizes that heroism is not all its cracked up to be.

Anodos is also able to experience something miraculous—his own death, which allows him to view his own life with clarity. It’s a wonderful sequence in the book and a powerful demonstration of the possibilities offered by the fantasy genre.

MacDonald was a theologian but there is no overt Christianity in Phantastes, save for its overall optimistic outlook that “something good will happen” at the end of our lives. Not surprisingly C.S. Lewis fell hard for its spell; his first reading of Phantastes at age 16 marked a turning point in his eventual career as a fantasy author. “That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized; the rest of me, not unnaturally, took longer. I had not the faintest notion what I had let myself in for by buying Phantastes,” Lewis said.

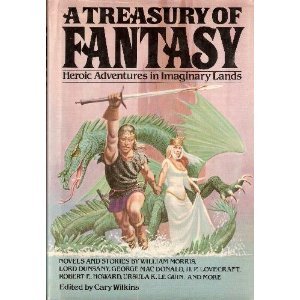

A final comment on my edition: The version I own is from A Treasury of Fantasy: Heroic Adventures in Imaginary Lands (Chatham River Press, 1984), which contains Arthur Hughes’ wonderful black and white illustrations. If you can find a copy, I recommend it for this reason.

A final comment on my edition: The version I own is from A Treasury of Fantasy: Heroic Adventures in Imaginary Lands (Chatham River Press, 1984), which contains Arthur Hughes’ wonderful black and white illustrations. If you can find a copy, I recommend it for this reason.

Thank you for this post! I grew up on George MacDonald, but somehow missed Phantastes. The Princess and the Goblin was a great read-aloud favorite in my house, as was “The Light Princess,” which I think had Maurice Sendak illustrations in one edition. “The Light Princess” is wryly funny, almost satirical, whereas most of the MacDonald I remember is dreamy and fae.

Thanks Sarah! I’ve got The Princess and the Goblin on my bucket list of material to be read one day.

This was the one of the first “adult” fantasy novel I ever read (as opposed to juvenile fiction), and I, too, fell hard under it’s spell. It began my love affair with both Victorian novels and fantasy novels and it has remained a favorite of mine since. I have read most of MacDonald’s fantasy and short stories; The Portent is another favorite of mine.