Ravenwood: The Forgotten Occult Detective

The phrase “pulp fiction” has been misused long before Quentin Tarantino appropriated it. For the past several decades nearly all genre fiction of the first half of the twentieth century has been considered pulp when in fact many of its bestselling authors (such as Edgar Rice Burroughs and Sax Rohmer) were published in the better-paying slicks and not the downscale pulps. The writing in the slicks tended to be more polished in sharp contrast to the breakneck pace of the pulps whose authors often hid behind house names and whose primary motivation was packing in as many thrills as possible in each story while still meeting their deadline.

The phrase “pulp fiction” has been misused long before Quentin Tarantino appropriated it. For the past several decades nearly all genre fiction of the first half of the twentieth century has been considered pulp when in fact many of its bestselling authors (such as Edgar Rice Burroughs and Sax Rohmer) were published in the better-paying slicks and not the downscale pulps. The writing in the slicks tended to be more polished in sharp contrast to the breakneck pace of the pulps whose authors often hid behind house names and whose primary motivation was packing in as many thrills as possible in each story while still meeting their deadline.

Ravenwood is a typical pulp creation. Nowhere near as successful as Doc Savage or The Shadow, Ravenwood appeared as a support feature in five issues of Secret Agent “X” in 1936. The creation of prolific pulp writer Frederick C. Davis, the character did much to pave the way for the occult crimefighter The Green Lama and was a strong influence on Marvel Comics’ Dr. Strange.

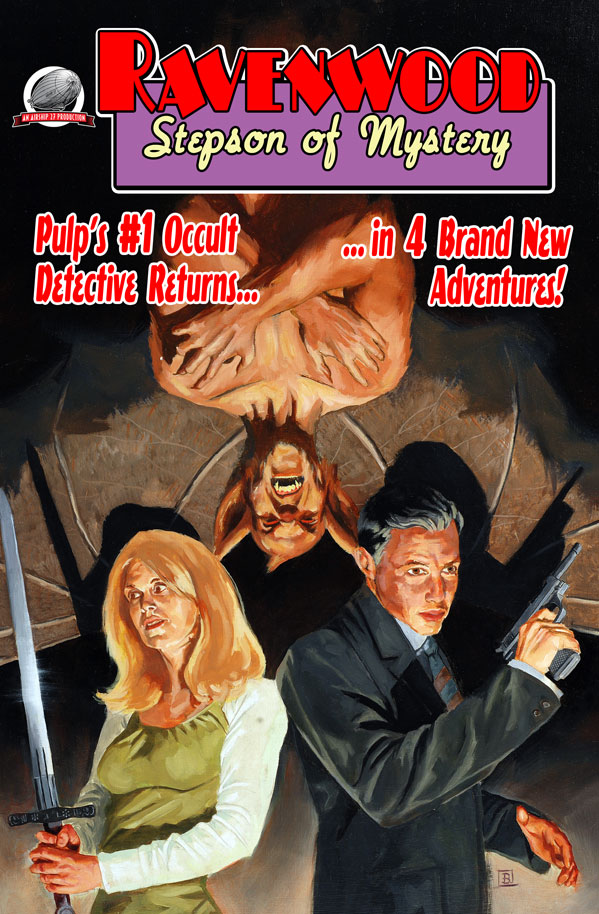

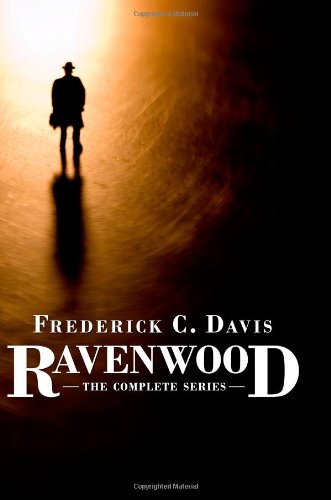

Altus Press collected Davis’ five original pulp stories in a single volume, Ravenwood: The Complete Series published in 2008. More recently, the acclaimed contemporary pulp-specialty publisher Airship 27 revived the character for an anthology of new stories from their talented stable of modern pulp writers. Their Ravenwood, Stepson of Mystery was published in 2010.

The original Ravenwood stories are fast-paced formulaic fun. Ravenwood is the son of Anglo-American parents who died of a fever in what used to be called the Orient at the turn of the last century. The orphaned boy returned to the United States to inherit his father’s estate accompanied by the nameless Tibetan shaman his father had saved from an attacking tiger. The Nameless One, as the aged sage is known, spends his days meditating and burning incense in Ravenwood’s penthouse sanctuary. He is a spectral presence dispensing eerily prescient proverbs to Ravenwood (now grown to adulthood and working as a private detective) who turns to the ghostly guru for advice at least once during each case.

The original Ravenwood stories are fast-paced formulaic fun. Ravenwood is the son of Anglo-American parents who died of a fever in what used to be called the Orient at the turn of the last century. The orphaned boy returned to the United States to inherit his father’s estate accompanied by the nameless Tibetan shaman his father had saved from an attacking tiger. The Nameless One, as the aged sage is known, spends his days meditating and burning incense in Ravenwood’s penthouse sanctuary. He is a spectral presence dispensing eerily prescient proverbs to Ravenwood (now grown to adulthood and working as a private detective) who turns to the ghostly guru for advice at least once during each case.

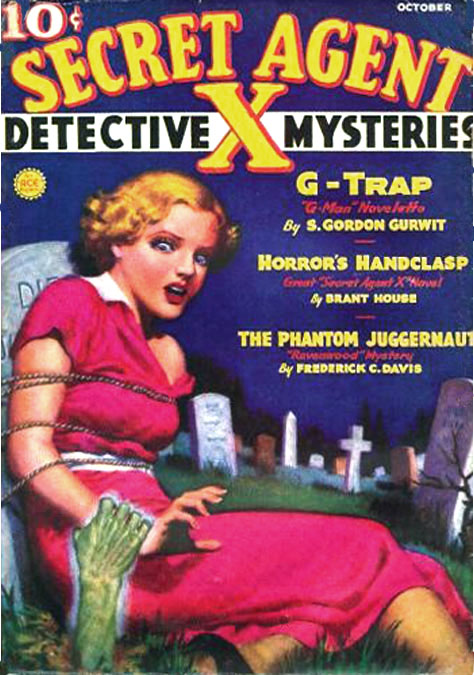

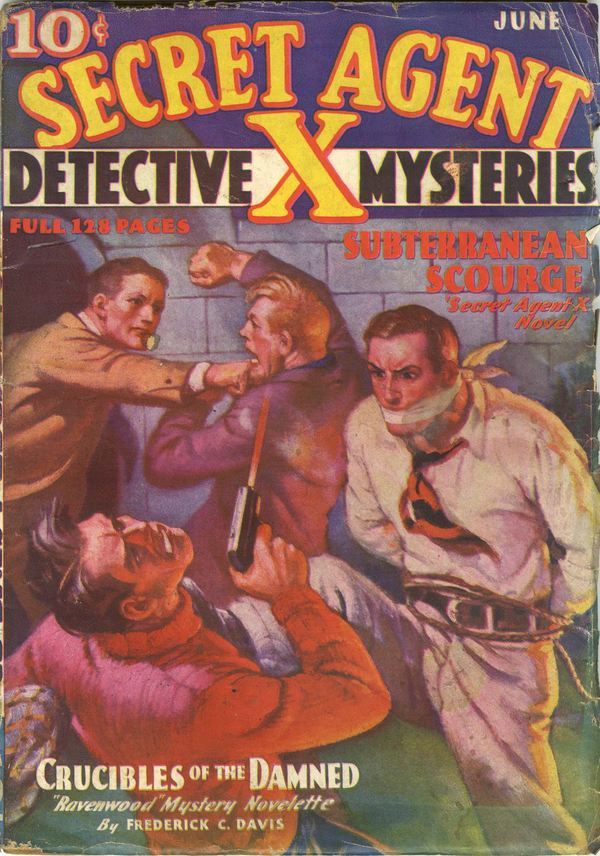

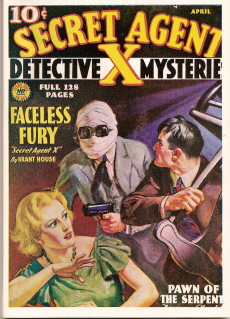

Ravenwood possesses moderate psychic abilities to the consternation of his otherwise implacable butler, Sterling and the endless frustration of the ever-skeptical Police Inspector Stagg who is convinced that Ravenwood’s abilities are a sham and is always looking for an opportunity to trip him up and expose him as a charlatan. The five original stories take Ravenwood through classic pulp paces and consistently provide rational solutions for seemingly supernatural occurrences from the stolen fortune hidden within the deadly Sealed Buddha in the character’s first appearance in “Murder Shrine” (March 1936) to a deadly ring loaded with mamba poison in “Pawn of the Serpent” (April 1936) to mobsters practicing alchemy in “Crucibles of the Damned” (June 1936) to Egyptian beetles dipped in poison to foster belief in a mummy’s curse amidst a disgraced scientist’s bizarre experiments in reviving fresh corpses in “Master of the Living Dead” (August 1936) until the character’s exploits concluded with the mystery of the killer automobile with no driver behind the wheel in “The Phantom Juggernaut” (October 1936).

The formula is a unique one in that Ravenwood’s psychic abilities and those of the Nameless One are presented as legitimate while the villains consistently use deception and fraud to disguise their crimes as supernatural events. Considering this fact, Ravenwood should cut poor Inspector Stagg some slack for doubting the detective. Ravenwood lives the life of an independently wealthy gentleman bachelor in Depression-Era New York. Davis does an admirable job of portraying the character as an eternal outcast at home neither in the West nor the East.

The formula is a unique one in that Ravenwood’s psychic abilities and those of the Nameless One are presented as legitimate while the villains consistently use deception and fraud to disguise their crimes as supernatural events. Considering this fact, Ravenwood should cut poor Inspector Stagg some slack for doubting the detective. Ravenwood lives the life of an independently wealthy gentleman bachelor in Depression-Era New York. Davis does an admirable job of portraying the character as an eternal outcast at home neither in the West nor the East.

The formula fails in as much as each story so closely follows the blueprint of the first. Ravenwood’s origin and Inspector Stagg’s skepticism are recycled as if being introduced for the first time in each of the four subsequent stories. Added to the similarity of fraudulent supernatural crimes are dark family secrets revealed in each story and one begins to appreciate why the character was more influential than successful in 1936. Happily, Airship 27’s writing team avoided these pitfalls for their 21st Century revival of the character. Wisely, they kept the stories in period and allowed their superior writing ability to fully realize the series’ potential for the first time since “Murder Shrine.”

Frank Schildiner’s “The Evil of Atlantis” is the standout story in this excellent collection. Schildiner pits Ravenwood against Paul Muller’s Sun Koh, a character often unfairly dismissed as a Nazi clone of Doc Savage. Muller’s German pulp stories were banned by the Nazi Party and, to the best of my knowledge, have never been translated into English (Art Sippo’s recent English language revival of the character in Sun Koh, Heir of Atlantis was published in 2010 by Age of Adventure. Sippo delivers well-written pulp adventures with a decidedly adult perspective coming off as a more literate Richard Jaccoma than a modern day Lester Dent in the process), but it is interesting to compare and contrast the character with Marvel Comics’ Atlantean anti-hero Namor, the Sub-Mariner (although it is unlikely that creator Bill Everett had even heard of Sun Koh when he created Namor in 1939).

Shildiner does a great job of breaking free of Davis’ formula while still remaining true to the characters and imbuing them with an internal continuity and natural development that their creator failed to achieve. Happily, Schildiner’s fellow writers do not disappoint, B. C. Bell’s “Onslaught of Abomination” comes closest to emulating Davis’ style, but not his limitations. While at first glance, both Bill Gladman’s “When Death Calls” and Bobby Nash’s “Jazz” come across as conventional mystery writers slumming among the pulps, upon reflection one realizes they are excellent matches for the material as both are writers of exceptional skill who succeed in breathing new life into a vintage pulp character and make the material more easily accessible to modern readers as well as delighting avid pulp enthusiasts. Airship 27 may have set their sights on reinvigorating the pulp genre, but their titles should actually be remembered for finally closing the gap between the pulps and the slicks and giving vintage pulp heroes and archetypes the polish they always deserved.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). A sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu is due for publication in December 2011. Also forthcoming is a collection of short stories featuring an original Edwardian detective, The Occult Case Book of Shankar Hardwicke and an original hardboiled detective novel, Lawhead. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com