London Calling: The Iron Heel and the Literature of Ideas

Last week I discussed Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker as an example of a true literature of ideas: a work structured not as a traditional narrative, with plot and character development as we know them, but instead built around the ideas that the work’s presenting, so that the book’s material is defined not by narrative but by the ideas at the core of its theme. As it happens, I recently stumbled across another example of this sort of thing.

Last week I discussed Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker as an example of a true literature of ideas: a work structured not as a traditional narrative, with plot and character development as we know them, but instead built around the ideas that the work’s presenting, so that the book’s material is defined not by narrative but by the ideas at the core of its theme. As it happens, I recently stumbled across another example of this sort of thing.

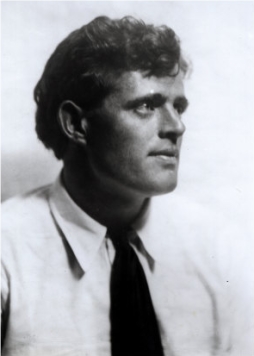

Published in 1907, Jack London’s The Iron Heel is an imaginative account of North America sliding into a totalitarian society. London, a socialist, wrote the book as a cautionary tale about the oligarchs of his era. It’s an odd thing, mixing journalism and (what we now call) dystopic science fiction with economic hectoring. It’s slow going, particularly in the first half, but the climax is exciting adventure writing. You can see why it didn’t catch on, but it’s still worth looking at.

(You can read the book here, here, or over here, or listen to an audio version over here. I note there was recently a piece about the book on Daily Kos; you can find that here.)

The book begins with a dinner hosted by a scientist and university professor, John Cunningham, at which he’s brought together a number of people, mostly clergymen, for a discussion of the state of the working class. One of the men at the dinner, though, is working-class socialist intellectual Ernest Everhard, who demolishes the clergy in an argument where he champions science over metaphysics. Cunningham’s daughter, Avis, is attracted to Everhard, and over subsequent chapters she investigates his assertions about class and society, coming to find out that he’s absolutely right about absolutely everything.

The book begins with a dinner hosted by a scientist and university professor, John Cunningham, at which he’s brought together a number of people, mostly clergymen, for a discussion of the state of the working class. One of the men at the dinner, though, is working-class socialist intellectual Ernest Everhard, who demolishes the clergy in an argument where he champions science over metaphysics. Cunningham’s daughter, Avis, is attracted to Everhard, and over subsequent chapters she investigates his assertions about class and society, coming to find out that he’s absolutely right about absolutely everything.

Avis and Ernest fall in love, as popular support for socialism grows and the oligarchs who run the country begin plotting to destroy the movement. Elections are held, a tipping-point is reached; violent and repressive means are used to try to keep the class structure in place. Finally, the oligarchs — who as a group are the Iron Heel of the title — foment a rebellion in Chicago, which they crush by outright military force as a show of power.

The book’s told from Avis Cunningham’s point-of-view, but with an odd double perspective. The story starts in 1912, and covers a few years in detail; Avis writes in 1932, as another revolt is in preparation. But there are also footnotes written seven hundred years in the future, which establish Avis’ narrative as a historical document. The footnotes tell us that the Second Revolt will fail as badly as the Chicago Commune, but that in the end, after centuries of rule by the Iron Heel, socialism will triumph and build a utopia.

The footnotes consciously eliminate any kind of traditional suspense. You know what’s going to happen, in broad outline at least, throughout the book. And the shape of the first half of the book suggests that suspense wasn’t on London’s mind. It’s a mix of Everhard spouting economic doctrine, footnotes quoting journalism and other writings from London’s own era (this is social satire with documented sources), and a few of what might be called ‘case histories’ describing the fates of particularly moral or particularly unlucky individuals under capitalism. It’s not gripping, but it is interesting to see London engaged in a variant of traditional sf writing. Instead of imagining a world, he’s re-imagining the world around him, describing it not only as a dystopia but also an inevitability caused by the laws of historical and economic development — and so presenting it to his readers.

The footnotes consciously eliminate any kind of traditional suspense. You know what’s going to happen, in broad outline at least, throughout the book. And the shape of the first half of the book suggests that suspense wasn’t on London’s mind. It’s a mix of Everhard spouting economic doctrine, footnotes quoting journalism and other writings from London’s own era (this is social satire with documented sources), and a few of what might be called ‘case histories’ describing the fates of particularly moral or particularly unlucky individuals under capitalism. It’s not gripping, but it is interesting to see London engaged in a variant of traditional sf writing. Instead of imagining a world, he’s re-imagining the world around him, describing it not only as a dystopia but also an inevitability caused by the laws of historical and economic development — and so presenting it to his readers.

The second half of the novel is somewhat more engaging, as Avis describes the world going to hell and the Iron Heel closing their fist around North America. We see the world become a complete dystopia, shaped by violence and massacres. Horrible, yes, but fun to read about. Still, the book only really catches fire in its final pages, as the battle of the Chicago Commune develops. We follow Avis caught up in a strange, surreal new kind of warfare, in which London imagines skyscrapers withstanding sieges like medieval castles, and describes hot-air balloons being used as warships (though it should be said the book as a whole is remarkably unlike the fantastic, adventure-fiction feel of steampunk).

The book ends abruptly after the Commune, literally in the middle of a sentence; Avis’ manuscript is interrupted. We’re left wondering what happens next, which seems to lead us back to the beginning of the book, and the footnotes describing the failed Second Revolt and the long rule of the Iron Heel and the final coming of socialist paradise. It’s tempting to try to read the footnotes as ironic, but realistically the tenor of the book urges against this approach, and there doesn’t seem to be enough to work with in terms of imagining an alternative future.

The book does have something of the feel of pulp science fiction. Ernest’s a solid proto-pulp hero, vigorous and aggressive and always smarter than everyone around him. He, like most of the other characters, is also undeveloped. You could call the characters archetypes, but for the most part they don’t even receive that level of individuation. In the end, unlike most pulp sf, Ernest’s heroism is ironic: his actions fail, and the triumph of socialism comes only through collective action and the unstoppable march of progress, not the individual man of action.

The book does have something of the feel of pulp science fiction. Ernest’s a solid proto-pulp hero, vigorous and aggressive and always smarter than everyone around him. He, like most of the other characters, is also undeveloped. You could call the characters archetypes, but for the most part they don’t even receive that level of individuation. In the end, unlike most pulp sf, Ernest’s heroism is ironic: his actions fail, and the triumph of socialism comes only through collective action and the unstoppable march of progress, not the individual man of action.

Although we’re still left with Avis, who emerges as the real hero of the book. For all that she goes into ecstasies about her love for Ernest, in the second half of the book we see her emerge as a competent and effective spy and socialist agent in her own right — or, at least, we have that development described to us. We see the Chicago Commune through her eyes, as she finds her way through the war zone that the city becomes. She’s the closest thing to a real person in the book, and while that’s not enough to make the book live as a traditional narrative, her perspective still holds some interest.

So the book has a minimal interest in character, and the plot is less a development of incidents caused or shaped by character than it is the recitation of various historical events, interspersed with lectures and illustrations of failures of the social system. There’s also not really any sense of place to the book, at least in its first half; oddly, the second half gives us not only the scenes in Chicago but also an extended description of a wilderness refuge for the socialist rebels. In the end, the drama’s minimal. The book has some ideas it wants to express, but does so not according to narrative logic but to the logic of the ideas — history is going to develop in a certain way, and so here is an illustration of things unfolding.

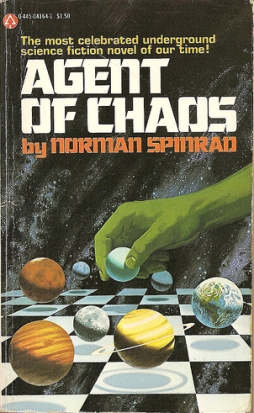

It’s vaguely similar to Asimov’s Foundation series, though less imaginative. You can also see points of similarity to a few other sf works; I was reminded now and again of Norman Spinrad’s Agent of Chaos, which imagined a hegemonic interplanetary government, an ineffective rebel organisation, thorough infiltration of one group by another, and a sense of history playing out according to certain rules. I also found myself thinking of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which (among other things) plays about with a communist organisation rebelling against societal powers, and concludes with a riot in a major American city.

It’s vaguely similar to Asimov’s Foundation series, though less imaginative. You can also see points of similarity to a few other sf works; I was reminded now and again of Norman Spinrad’s Agent of Chaos, which imagined a hegemonic interplanetary government, an ineffective rebel organisation, thorough infiltration of one group by another, and a sense of history playing out according to certain rules. I also found myself thinking of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which (among other things) plays about with a communist organisation rebelling against societal powers, and concludes with a riot in a major American city.

But The Iron Heel is ultimately none of these books. It’s the story of an idea, as London imagined the idea developing into the future — specifically, into a future predicted by the idea itself. Personal heroism and drama aren’t needed, the book implicitly argues. What will come is what will come. It’s inevitable. This is, therefore, specifically not a literature of character or of narrative. This is a literature of ideas.

It’s not the easiest thing to read. But it does suggest a different way that sf in general might have gone.