Classic Alternatives: Keith Roberts’ Pavane

I’ve always been fascinated by history, which is one reason why I write about it. So by extension one of the kinds of speculative fiction which has always fascinated me is the alternate history tale. Whether as a ‘pure’ alternate history tale, describing a world where things just happened to go a different way than we knew, or as a ‘warped’ history in which deliberate meddling has created some new reality, the rethinking of historical assumptions is challenging and invigorating — at least, up to a point. The changes have to make sense.

I’ve always been fascinated by history, which is one reason why I write about it. So by extension one of the kinds of speculative fiction which has always fascinated me is the alternate history tale. Whether as a ‘pure’ alternate history tale, describing a world where things just happened to go a different way than we knew, or as a ‘warped’ history in which deliberate meddling has created some new reality, the rethinking of historical assumptions is challenging and invigorating — at least, up to a point. The changes have to make sense.

I think a lot of science fiction and fantasy requires careful attention to setting; attention in constructing a setting, attention in how the setting is communicated to the reader, and attention in working the setting and its communication smoothly into the narrative. Along, of course, with attention to how the setting affects character, and, ultimately, the language a character uses and the language in which the story is told. The alternate-history story is an extreme example of all these things. It’s the setting that makes it the story it is. And in changing history, the writer makes decisions about character, style, and — implicitly — theme and structure; as in any kind of sf, what kind of fictional world the writer creates is intimately connected with what the story’s about and how it’s told.

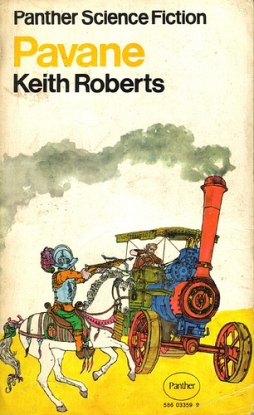

Which brings me around to Keith Roberts’ novel Pavane. It’s a set of linked short stories, describing a world in which Queen Elizabeth I of England was assassinated, the Spanish Armada conquered England, and Europe remained wholly Catholic. The book, first published in 1966, takes place in the late twentieth century of this other world, in which technological and social progress has been slowed by the authoritatian hand of the Church. It moves from character to character, showing developments over the course of generations as some things change and some things do not.

It’s a fascinating book, but not necessarily for its sf aspects. Roberts’ sense of imagery and character is very strong, and most of the short stories focus on the perceptions and history of a single person whose significance to the overall development of the alternate world is not immediately apparent. Roberts explores his characters, their lives and feelings and insights, and the sense of them as real people living in a real world with its own history and weight is convincing.

It’s a fascinating book, but not necessarily for its sf aspects. Roberts’ sense of imagery and character is very strong, and most of the short stories focus on the perceptions and history of a single person whose significance to the overall development of the alternate world is not immediately apparent. Roberts explores his characters, their lives and feelings and insights, and the sense of them as real people living in a real world with its own history and weight is convincing.

Which is impressive, because I have a lot of reservations about the nature of the world he’s created. I found myself unconvinced that the Early Modern Catholic Church would be able to hold back developments in science and politics (even if they wanted to); Roberts seems to see the Church as temporally powerful in a way that I’m not sure is really tenable. And even if I were to believe that the Church would develop the authority he suggests, I’d doubt it could maintain it. The Protestant Reformation was, among other things, a way for rulers of states to get out from under the authority of Rome; even if one Reformation was crushed, why wouldn’t another develop?

Roberts thought through patterns of trade and social development, and then mostly kept them offstage, allowing the action of events to show how classes were rising or falling in power. But perhaps too much is kept offstage; the prologue, which is a two-page overview of events between the late sixteenth and late twentieth centuries, tells us that Philip of Spain conquered England — but then later in the book England (not Britain) has an independent King Charles, who dabbles in political machinations against the power of Rome. On the other hand, the Inquisition is active in a way that recalls Spain after the Reconquista; it’s not clear if it’s a branch of the Roman Inquisition, or some entirely new English Inquisition. In any event, you wonder how heresy can be so widespread that the Inquisition should have the status it does, and also so scattered that no credible resistance to Rome has emerged.

Ultimately, though, the paradox of Pavane is that you believe in the world because you believe in the characters, and you believe in the characters because they seem to be the product of a tangibly real world. Roberts’ characters are utterly concrete, almost too thoroughly-realised; they don’t surprise you, they don’t have unexpected thoughts or sudden intuitive leaps or crack a joke you don’t see coming, but that’s because they’re so much a logical extension of their background, of class and gender and geography. And language: the way they speak, their word choices, help to build the sense of the word. Tolkien once observed of one of his characters that he used archaic diction because he did not think as a modern man did; that’s an example of how language shapes and demonstrates character, and Roberts understands that. On a subtler scale, his characters use expressions and turns of phrase that tell us simply who they are.

Ultimately, though, the paradox of Pavane is that you believe in the world because you believe in the characters, and you believe in the characters because they seem to be the product of a tangibly real world. Roberts’ characters are utterly concrete, almost too thoroughly-realised; they don’t surprise you, they don’t have unexpected thoughts or sudden intuitive leaps or crack a joke you don’t see coming, but that’s because they’re so much a logical extension of their background, of class and gender and geography. And language: the way they speak, their word choices, help to build the sense of the word. Tolkien once observed of one of his characters that he used archaic diction because he did not think as a modern man did; that’s an example of how language shapes and demonstrates character, and Roberts understands that. On a subtler scale, his characters use expressions and turns of phrase that tell us simply who they are.

So the language makes the characters, and by extension makes the world as well. Roberts’ gift for precise description is crucial here, creating landscapes, or at least a landscape — most of the novel takes place in Dorset, in south-west England. In Roberts’ telling, there’s a quality to the land that’s timeless, and therefore outside history; to an extent, the book might be said to be about the conflict of the identity of the land with the history that plays out upon it.

Here’s a paragraph from a bit past the middle of the book:

This was a wild, mournful place. An eternal brooding seemed to hang over the bulging cliffs; a brooding, and worse. An enigma, a shadow of old sin. For here once a mad priest had come, and called the waves and wind and water to witness his craziness. Becky had heard the tale often enough at her mother’s knee; how he had taken a boat, and ridden out to his death; and how the village had hummed with soldiers and priests come to exorcise and complain and quiz the locals for their part in armed rebellion. They’d got little satisfaction; and the place had quietened by degrees, as the gales went and came, as the boats were hauled out and tarred and launched again. The waves were indifferent, and the wind; and the rocks neither knew nor cared who owned them, Christ’s Vicar or an English King.

The passage obviously pits the world of nature, without history, against the smaller world of human activity. The recurring verbal focus on wind and water seems to embody the physical recurrence of these things in weather and the seasons. But more than that, I think the rhythm of the sentences, with their frequent semi-colons seeming to mediate them, helps emphasise the rhythm of nature. I think also that the image of a girl learning stories at her mother’s knee suggests cycles as well, and so does the casual reference to boats “hauled out and tarred and launched again” — which also helps ground the story in the world of work, vital both to this story and to the novel as a whole, which seems most comfortable in describing working-class life and the experience of those low down on the social hierarchy.

Certainly word choices help bring the scene alive. The soldiers and priests come to “complain,” which is nice, and “quiz the locals,” which is excellent, because it seems to nod at two senses of the word, both ‘interrogate’ and ‘mock’. It all seems to stand apart from the many and contradictory adjectives given to the land — “wild”, “mournful”, “brooding”, “enigma”, “indifferent”. The land moves from an active force to something grander and impassive; it’s a character, and one that’s more surprising than most of the humans.

Certainly word choices help bring the scene alive. The soldiers and priests come to “complain,” which is nice, and “quiz the locals,” which is excellent, because it seems to nod at two senses of the word, both ‘interrogate’ and ‘mock’. It all seems to stand apart from the many and contradictory adjectives given to the land — “wild”, “mournful”, “brooding”, “enigma”, “indifferent”. The land moves from an active force to something grander and impassive; it’s a character, and one that’s more surprising than most of the humans.

Or than the story as a whole. Unfortunately, if the characters are impressive but unsurprising, so are most of the stories. They’re well-told, with precise images, but the plots are mostly predictable, in broad strokes if not precise outlines. As a whole, the book seems to me to lose its way quite badly in the last two pieces, especially in the “Coda” which tries to wrap up the whole story and explain away various mysteries running through the book. The explanations seem forced, the ending provided incredible — perhaps because it’s not based in character.

Towards the end, one character is given a speech which seems to sum up the novel’s theme; and if the speech is too neat, it gets to the heart not only of this book but of many alternate-history tales: “It’s like a … dance somehow, a minuet or a pavane. Something stately and pointless, with all its steps set out. … [S]ometimes I think life’s all a mass of significance, all sorts of strands and threads woven like a tapestry or a brocade. So if you pulled one out or broke it, the pattern would alter right back through the cloth. Then I think … it’s all totally pointless, it would make just as much sense backwards as forwards, effects leading to causes and those to more effects …”

The character goes on, ruminating on past events we’ve seen unfold, and how those events led to the dramatic things she is now living through. History as a dance; as a pretermined pattern. Indeed, as a pattern that could be entirely changed with one small variation. The novel has shown us characters whose ability to change the world seems minimal, but who collectively seem to threaten to bring about a major shift in the order of things.

The character goes on, ruminating on past events we’ve seen unfold, and how those events led to the dramatic things she is now living through. History as a dance; as a pretermined pattern. Indeed, as a pattern that could be entirely changed with one small variation. The novel has shown us characters whose ability to change the world seems minimal, but who collectively seem to threaten to bring about a major shift in the order of things.

How much does one individual person change the world? How much does change — and history is simply the tracking of change over time — come about through the actions of many people, interacting over years? How much, on the other hand, is history a function of relatively impersonal processes — of systems, and social classes, and technologies? And what, in the end, is the point?

Or is it a mistake to look for a point in history? Or in alternate history? Or, put another way: if you look for a point, aren’t you in danger of finding it? One of the first alternate histories was written by a French veteran of the Napoleonic wars, who imagined what would have happened if Napoleon had been victorious in Russia — he would have established a benevolent world-empire, and the world would become a utopia. Alternate history as consolation. What he wanted to be true he imagined as possible, whether it was credible or not.

Similarly, my doubts about the internal credibility of Roberts’ world cause the theme he’s trying to suggest to seem — to me — unconvincing. I believe in the dance only through the dancers. That’s not really enough.

I think Pavane’s a good book, and Roberts was a profoundly skilled writer. He died in 2000, having written nine novels and a number of short stories. Pavane seems to be best known, with Anthony Burgess having named it one of the ninety-nine best novels of the 20th century (or at least between 1939 and 1983). I’ll certainly be keeping my eye out for any more of Roberts’ work. As alternate history I think it’s unsucessful. But by focussing on character it demonstrates how to make even what might be a weak premise feel true — only for a time, perhaps, but for human beings time is all we can know.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

[…] See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here, and Matthew David Surridge’s detailed review of Pavane here. […]

[…] Treasures: Pavane by Keith Roberts Classic Alternatives: Keith Roberts’ Pavane, by Matthew David […]