Gemmell’s Legend Remains a Rousing Call to Arms

I love pre-battle speeches. Arnold’s “Then to hell with you!” prayer to Crom before the battle of the mounds, and Theoden’s exhortation to the Rohirrim just before their charge on the Pelennor Fields (“spears shall be shaken, shields shall be splintered!”), to name two, make me want to pick up spear and shield and wade into the fray (of course Kenneth Branagh’s Band of Brothers/St. Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V remains the best). Even though I’d never want to fight in a real shield wall, the power of these speeches admittedly gives me second thoughts.

I love pre-battle speeches. Arnold’s “Then to hell with you!” prayer to Crom before the battle of the mounds, and Theoden’s exhortation to the Rohirrim just before their charge on the Pelennor Fields (“spears shall be shaken, shields shall be splintered!”), to name two, make me want to pick up spear and shield and wade into the fray (of course Kenneth Branagh’s Band of Brothers/St. Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V remains the best). Even though I’d never want to fight in a real shield wall, the power of these speeches admittedly gives me second thoughts.

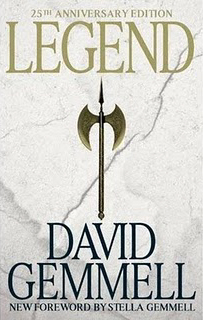

That’s probably why I loved reading David Gemmell’s Legend (1984) so much. Gemmell’s debut novel is more or less a buildup to (and execution of) a monumental battle scene, and its rousing inspiration speeches don’t disappoint. In terms of the printed page Legend ranks right up alongside Steven Pressfield’s spectacular Gates of Fire for galvanizing battle-speeches.

Here’s one sample as delivered by Druss, the eponymous “legend” from whom the novel derives its name. Druss is an aging warrior and a veteran of innumerable battles who dusts off his axe Snaga and treks to the defense of the fortress Dros Delnoch, like an aging athlete coming out of retirement to prove he can still play. On the eve of the final battle, he rouses the outnumbered Drenai to stand with him, one last time:

“Some of you are probably thinking that you may panic and run. You won’t! Others are worried about dying. Some of you will. But all men die. No ever gets out of this life alive.

I fought at Skeln Pass when everyone said we were finished. They said the odds were too great, but I said be damned to them! For I am Druss, and I have never been beaten, not by Nadir, Sathuli, Ventrian, Vagrian, or Drenai.

By all the gods and demons of this world, I will tell you now — I do not intend to be beaten here, either!” Druss was bellowing at the top of his voice as he dragged Snaga into the air. The ax blade caught the sun and the chant began.

“Druss the Legend! Druss the Legend!”

If you like the above monologue, you’ll probably love Legend. If not, well, there’s always Magic Kingdom for Sale: Sold.

More than great speeches, Legend is a paean to the martial spirit and the comradeships forged in war. It teaches us to live lustily, fight hard should the need arise, and die well when your time comes.

If this all sounds a bit melodramatic, Gemmell apparently was driven to write Legend after receiving a (mis) diagnosis of cancer. He literally thought the novel might be his last statement to the world. There’s a great summary of his life and work by John J. Miller of the Wall Street Journal, here.

Under Druss and Regnak, the Earl of Bronze, the massively outnumbered Drenai (10,000 vs. an invading force of 500,000 Nadir) hold out in Dros Delnoch, seeking to stave off an invasion that will result in the end of the once-proud Drenai empire. Dros Delnoch is a keep ringed by six walls, each with a name that seem to resemble the stages of a man staring down the inevitability of his own death. These include Eldibar (exultation), Musif (despair), Kania (renewed hope), Sumitos (desperation), Valteri (serenity), and Geddon (death). (The first, Elibar/exultation may seem like a stretch, but as Legend explains it’s the exultation of facing the enemy, finally, and feeling alive in the bright colors of the conflict, waking up to the wonder that is the life which we often take for granted). Again and again Ulrich offers the defenders of Dros Delnoch the chance to surrender, but under Druss and Rek they fight on.

Gemmell delivers on the final battle, which delivers its carnage over more than 100 pages (better than a third of the book). But more than the details of the battles or tactics of the siege, Legend is really about the men (and handful of women) living their lives on the brink of death and trying to stay strong in their last days. The life they live now seems much brighter and worthwhile because it’s being bled out, day by day, on the walls of Dros Delnoch.

In his 1936 famous lecture “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”, J.R.R. Tolkien delivered to the world his theory of northern courage. In short, it says that when all hope is lost, and death is not only imminent, but inevitable, you fight on and die because it’s ennobling and the clearest expression of the will. No sacrifice is in vain because we cannot know the outcome. Dying for a cause may inspire some future warrior to pick up his sword for the cause and eventually win; death itself may be only a door to something greater beyond the circles of this world. I would never speak for a cancer victim (Gemmell himself was not one; he died at the untimely age of 56 from a heart problem), but it seems there are some valuable lessons in Legend about living one’s life to the fullest and never giving in.

Yes, I was mightily impressed with Legend — and pleasantly surprised. I do have to admit that Legend was not my first encounter with Gemmell. Previously I had read White Wolf and Hero in the Shadows. The former I found thoroughly below average, and I hate to admit it but I failed to finish the latter. I can now say from experience that if you’ve come to Gemmell in the same way, through his later fiction, and perhaps haven’t been so impressed, I’d recommend starting at the beginning, with the Legend that started it all. Now I get what the hype was all about.

A few final words about David Gemmell: There’s now a writing award established in his memory, and for a nice summary of his entire corpus here’s a fine appreciation by Steve Tompkins and Wayne MacLaurin right here on Black Gate.

Inspiring salutation yourself, Brian. This is an awesome novel and you’ve provided an equally powerful post here on BG.

his works are translated to spanish, but the edition in Spain start the Drenai cycle with Waylander and legend is the fourth book in the series I think, but in the forums some people suggest reading first the books of Druss

and what about his blood and thunder version of the war of Troy?

Legend I must write it in capital letters

[…] (despair), Kania (renewed hope), Sumitos (desperation), Valteri (serenity), and Geddon (death). Follow this link to an excellent article on the book and how the whole work is a metaphor for Gemell’s feeling […]

[…] to his books, an obituary from The Guardian, a retrospective of his life and career from this site, and a look back at his first novel, Legend. I’ve only read a couple of his works myself, his early novels Legend and Waylander, but knowing […]