Don’t Look Now, It’s the Birds: The Weird Tales of Daphne du Maurier

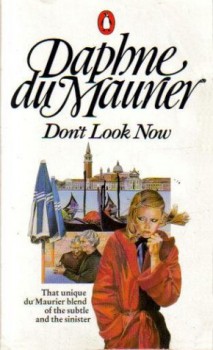

Don’t Look Now: Stories

Don’t Look Now: Stories

By Daphne du Maurier, selected by Patrick McGrath

NYRB Classics (368 pages, $15.95, October 2008)

I have recently started an immersive journey through Cornwall, although not of the physical variety, since economically I don’t have the luxury of taking myself there. After a few years of vague fascination with the tip of the southwestern peninsula of Great Britain, which reaches out into the Atlantic to terminate in the pincer claw of Lizard Point and the Penwith Peninsula, I started to do harder research into its history and customs that separate it in weird and wonderful ways from the rest of the island that lays east of the river Tamar. My reason for this intensification of interest is, of course, for writing purposes. And if anyone wants to make a journey into Cornwall that involves fiction, he or she will have to spend some quality time with the Grand Dame of the land of tinners and smugglers, Daphne du Maurier.

Du Maurier (1907–1989) achieved enormous success as an author of twentieth century popular literature. On first publication, most of her novels received dismissive critical notices as “romantic thrillers for women,” while they ran through printing after printing to satisfy public demand. However, du Maurier’s novels have managed to escape the dustbin of most bestsellers of yesteryear and they remain in print and popular as ever today. Critical opinion has also turned around, and the author is now respected as an excellent wordsmith and crafter of plots, a literary descendant of Wilkie Collins, and as the twentieth century “voice” of Cornwall.

Most of du Maurier’s novels are historicals with emphasis on romantic suspense and Cornish settings: Jamaica Inn (1936), Frenchman’s Creek (1942), and The King’s General (1946). Her most famous work is Rebecca (1938), a contemporary-set Gothic masterpiece about an unnamed woman who marries into a sinister legacy in a mansion perched on the cliffs of what must be—although never stated as such—the jagged coast of north Cornwall. Rebecca’s reputation was furthered immortalized in the 1940 film version that brought Alfred Hitchcock from the U.K. to Hollywood for the first time and set the standard for the “creepy maid” figure in Judith Anderson’s Oscar-winning performance as Mrs. Danvers.

But du Maurier had an impact on the “weird tale” as well in her short stories, where she explored supernatural and perverse aspects that are only shadows on the Gothic fringes of her novels. Two of them, “The Birds” and “Don’t Look Now,” are classics of supernatural horror that have also received the compliment of popular film adaptations, although du Maurier expressed dislike for Hitchcock’s movie The Birds.

The New York Review Books Classics line has rescued nine of du Maurier’s short works for the collection Don’t Look Now: Stories (2008), and I think this volume is a must for anyone interested in the twentieth-century weird tale. At the very least there is the title story and “The Birds,” two pieces that on their own prove that du Maurier was more than the “romantic bestseller” her critics like to damn her as, but a superb writer capable of intricate, multilayered storytelling and suspense.

“Don’t Look Now,” which was first collected in 1971 in Not after Midnight, uses the most common theme in du Maurier’s supernatural tales: clairvoyance. John and Laura, a married couple vacationing in Venice to ease the pain of the death of their young daughter, encounter a pair of strange old English women at a restaurant. One of these twins is blind and claims she is a psychic; she informs Laura she can “see” her daughter Christine sitting between the couple. Laura goes into a bizarre elation over the revelation, but John is wary of the pair and suspects something else is going on. Du Maurier uses the narrative focus on John to create the sense of suspicion and skepticism in the reader, while at the same time suggesting that John is an untrained psychic himself.

“Don’t Look Now,” which was first collected in 1971 in Not after Midnight, uses the most common theme in du Maurier’s supernatural tales: clairvoyance. John and Laura, a married couple vacationing in Venice to ease the pain of the death of their young daughter, encounter a pair of strange old English women at a restaurant. One of these twins is blind and claims she is a psychic; she informs Laura she can “see” her daughter Christine sitting between the couple. Laura goes into a bizarre elation over the revelation, but John is wary of the pair and suspects something else is going on. Du Maurier uses the narrative focus on John to create the sense of suspicion and skepticism in the reader, while at the same time suggesting that John is an untrained psychic himself.

The situation turns more unreal when Laura suddenly has to return to England when their son gets in an accident. Before John can follow her, he believes he sees Larua riding on a boat with the English women, setting him on a frantic search for her in Venice. In the middle of these strange events, almost coming in under the crack of the door like a draught, is news that a serial killer is stalking the soggy streets of the city.

“Don’t Look Now” is a masterful novelette; du Maurier’s control of information, her layering of events, and then the astonishing conclusion that shows every piece of the story has been orchestrated specifically, is amazing to read. Nicholas Roeg’s 1973 film perfectly captures this, keeping close to the story with a few additions for the longer form (the daughter’s death—from drowning instead of meningitis—opens the movie, while the novelette starts in Venice). I saw the movie long before reading the story, and the visual puzzles it presents made me wonder exactly how it could have been rendered in prose. Reading du Maurier’s story shows that Roeg realized the best way to transfer the novelette’s subtlety was to use images, seemingly in unrelated montages and juxtapositions, as the main storytelling tool. The result is a fascinating syncretic effect; the movie and the story enhance each other so that it is hard to believe that one could exist without the other. Du Maurier herself was very pleased with the film, and stated that of the adaptations made from her work, only the 1940 Rebecca and Don’t Look Now satisfied her.

While “Don’t Look Now” is a paragon of subtlety, surprise, and structure, “The Birds” is a monument of unrelenting fear. There are few stories in the English language as horrifying as this novelette about an inexplicable avian assault on a farmhand and his family’s cottage on the wind-beaten coast of Cornwall. A sudden change in temperature in December may be the initial cause of the waves of birds of all species turning on the family, but it becomes terrifyingly apparent through reports on the wireless that the birds are attacking across all of Great Britain. At first the outside world seems to feel the incidents are semi-comic, but farm worker Nat Hocken senses that a feathery apocalypse is coming and prepares to defend his wife and two children from it.

While “Don’t Look Now” is a paragon of subtlety, surprise, and structure, “The Birds” is a monument of unrelenting fear. There are few stories in the English language as horrifying as this novelette about an inexplicable avian assault on a farmhand and his family’s cottage on the wind-beaten coast of Cornwall. A sudden change in temperature in December may be the initial cause of the waves of birds of all species turning on the family, but it becomes terrifyingly apparent through reports on the wireless that the birds are attacking across all of Great Britain. At first the outside world seems to feel the incidents are semi-comic, but farm worker Nat Hocken senses that a feathery apocalypse is coming and prepares to defend his wife and two children from it.

The inescapable menace of the birds is horrifying, and du Maurier elevates the tension using the telescoping effect of only showing the view of the Nat Hocken. Through snatches from the radio, sounds of crashing planes, and discoveries of bodies, du Maurier creates the sense of the world ripping apart, with a small group of characters adrift in the end of all things. The recent shadow of World War II breathes through it all, the feeling of people huddled in shelters as bombs fell above them.

Alfred Hitchcock made a great movie from “The Birds” in 1963, but I understand why du Maurier had no love for it. Hitchcock created a different sort of tale, wryly mixing what seems at first to be a light soap opera with sudden murderous bird strikes. Most striking, he moved the setting to a pleasant sunny northern California town, far from the unstable and lonely world of north Cornwall. Hitchcock’s movie uses the human conflict as a mirror to the bird attacks, while du Maurier focuses on isolation and horror. Put them side by side, I think Hitch comes up short. Du Maurier’s story is far scarier and even more pessimistic.

Ghost stories would seem a natural for du Maurier’s Gothic tastes, but they crop up only occasionally in her works. “The Escort,” first published in 1980 in the collection The Rendezvous but likely written during World War II, is an unsurprising variation of the “ghost ship” subgenre. A tramp steamer making for home across German U-Boat prowled waters picks up a strange escort from out of the mist when a Nazi sub threatens to sink them. It is an ordinary tale, but du Maurier makes it worth reading through the powerful way she creates the terror of the men aboard the Ravenswing as they face certain death in the North Sea from the enemy below.

Another earlier work that was published in Rendezvous, “Split Second,” ventures into territory familiar to viewers of The Twilight Zone: alienation from the abrupt and inexplicable transformation of a person’s identity and environment. Mrs. Ellis, a fastidious widow whose life centers on her nine-year-old daughter, goes out from one day on an errand and then returns to find that other people are living in her home . . . and have been living there for many years. The story puts Mrs. Ellis on the defensive, demanding from everyone that there must be an explanation—possibly a vast conspiracy—for why everything connected to her life appears to have been erased. Readers will start to understand before Mrs. Ellis what has happened because of small clues; regardless, this isn’t a story that lives or dies depending on a twist close. It’s life comes from how it well it shows a life thrown into incomprehensible chaos, and it succeeds in that affect, although perhaps running about ten pages longer with Mrs. Ellis’s denials than necessary.

Another earlier work that was published in Rendezvous, “Split Second,” ventures into territory familiar to viewers of The Twilight Zone: alienation from the abrupt and inexplicable transformation of a person’s identity and environment. Mrs. Ellis, a fastidious widow whose life centers on her nine-year-old daughter, goes out from one day on an errand and then returns to find that other people are living in her home . . . and have been living there for many years. The story puts Mrs. Ellis on the defensive, demanding from everyone that there must be an explanation—possibly a vast conspiracy—for why everything connected to her life appears to have been erased. Readers will start to understand before Mrs. Ellis what has happened because of small clues; regardless, this isn’t a story that lives or dies depending on a twist close. It’s life comes from how it well it shows a life thrown into incomprehensible chaos, and it succeeds in that affect, although perhaps running about ten pages longer with Mrs. Ellis’s denials than necessary.

“Kiss Me Again, Stranger” sounds like a film noir title. This story, published in 1952 in the same volume with “The Birds,” does have some classic elements of the noir genre, with a movie-theater setting and a mysterious female tempting a lonely male. But the most noir aspect is how it looks at the way sudden, uncontrolled love can twist a person’s world. An unnamed man encounters an usherette at a theater who entrances him a way no other woman has before. He uncharacteristically follows her on an impulse onto the bus when she leaves for the night. Despite her strange insouciance toward him, he finds himself passionate about her, planning out a romantic life with “his girl.”

Of course this cannot reach a happy conclusion, not this sort of dizzy love. The girl wants to get off the bus at a cemetery. Any cemetery will do. Now you think you know where du Maurier is heading with this . . . but you’re wrong. The story wraps brutality in a crust of the sugary tenderness of a man who believes he’s found love for the first time, making for a perfect noir confection.

The strangest story is the collection is “The Blue Lenses” (1959), which uses a different kind of clairvoyance to create an inescapable nightmare. Mrs. Marda West, after undergoing surgery to save her eyesight, wakes up to find the monochrome blue lenses fit into her eyes make her see everyone with the heads of animals. The effect is comic when it first happens (the two nurses attending her are a cow and kitten respectively), but grows frightening as it becomes obvious that Mrs. West has gained the ability to see people as they really are—and how ghastly a power this is. As with “Split Second,” the story has a drawn out middle that dwells too much on the point after it has been established, but the ending is a surprise that draws a line between outer and inner perception.

The strangest story is the collection is “The Blue Lenses” (1959), which uses a different kind of clairvoyance to create an inescapable nightmare. Mrs. Marda West, after undergoing surgery to save her eyesight, wakes up to find the monochrome blue lenses fit into her eyes make her see everyone with the heads of animals. The effect is comic when it first happens (the two nurses attending her are a cow and kitten respectively), but grows frightening as it becomes obvious that Mrs. West has gained the ability to see people as they really are—and how ghastly a power this is. As with “Split Second,” the story has a drawn out middle that dwells too much on the point after it has been established, but the ending is a surprise that draws a line between outer and inner perception.

The shortest pieces in Don’t Look Now are “La Sainte-Vierge” and “Indiscretion,” both collected for the first time in Early Stories (1959). Both are about the daily illusions about the faith of lovers and spouses under which most people live. “The Sainte-Vierge” is a cynical fable where the viewer sees past the veil that blinds but also blesses a pious Breton girl. “Indiscretion” has the veil ripped away when a single sentence, said at the wrong time, destroys three people. “The Sainte-Vierge” is little more than a vignette, but “Indiscretion” has a complex subtext that belies the narrator’s claim that it was only the single spoken comment that ruined those lives.

The collection ends with the novella “Monte Verità,” which was first collected in the same 1952 volume with “The Birds” but is the opposite of it in tone, achieving a gentle mysticism. This work might be du Maurier’s tribute to Algernon Blackwood, sharing a love of mountain climbing and the numinous and transformative power of the great peaks of Europe. The unnamed narrator tells how his best friend Victor married a woman named Anna, who then vanished into a mysterious pre-Christian convent located on Monte Verità (the location is undisclosed, but the narrator’s hints make it seem likely it is in the Italian Alps). Unlike a few of the longer pieces in the collection, “Monte Verità” feels ideally suited to its length, pacing out the mystery through the use of the narrator and maintaining a slow, transcendent rise parallel with its ambiguity.

Don’t Look Now: Stories should not be confused with another du Maurier collection titled Don’t Look Now, which is a re-titling of Not after Midnight and contains five stories written around 1971.

This collection looks supercool. I will put it on my wish list! Thanks for this blog!

Your description of the story “Blue Lenses” gives me new insight into the video of the song “I Say Fever,” by Ramona Falls (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ga0ohgZFVqc)