Vexed Hierarchies

Another year’s drawing to a close, and with it the first full decade of the twenty-first century. It’s a time for looking back, for thinking over what’s happened and what’s going on, in fantasy fiction and elsewhere. I don’t pretend to be in a position to make any worthwhile assessment of fantasy as a whole; but I do want to write about a change that seems to be in process right now. I think it’s a positive change, and potentially a radical one. And I can remember the moment I realised it was happening.

Another year’s drawing to a close, and with it the first full decade of the twenty-first century. It’s a time for looking back, for thinking over what’s happened and what’s going on, in fantasy fiction and elsewhere. I don’t pretend to be in a position to make any worthwhile assessment of fantasy as a whole; but I do want to write about a change that seems to be in process right now. I think it’s a positive change, and potentially a radical one. And I can remember the moment I realised it was happening.

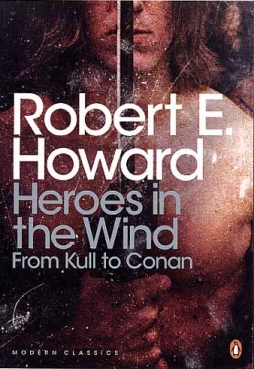

It was when I saw a collection of Robert E. Howard short stories published by Penguin Books.

Let me firstly explain why this was a shock. When I was a kid, Penguin seemed to be a publisher of self-consciously literary books; orange-spined paperbacks featuring mostly English people doing resolutely ordinary everyday things. This wasn’t accurate, as Penguin published sf writers, from Fred Hoyle to Keith Laumer to Fred Saberhagen, as well as mysteries, and writers like Ian Fleming and P.G. Wodehouse; but the perception was that the orange-spined books were realist fiction, and ambitious on a level above the rest. They didn’t interest me at the time, but I gathered from the adults around me that these books represented, in some way that was never clearly articulated, a literary quality beyond the sf and fantasy that I was reading.

As a child and young teenager I received a general idea of a hierarchy of literary value, never precisely enunciated, but picked up from the attitudes of my parents and my teachers and other adults. The scale went from my parents’ red-jacketed collection of Dickens, to the orange-spined Penguins, on down through school-approved sf writers like, say, Ursula Le Guin, to less respectable writers such as Robert E. Howard or Michael Moorcock, and then down to American comic books, perhaps the lowest of the low. (European comics were largely outside the scale I perceived; Japanese comics hadn’t yet really made the journey overseas.)

As a child and young teenager I received a general idea of a hierarchy of literary value, never precisely enunciated, but picked up from the attitudes of my parents and my teachers and other adults. The scale went from my parents’ red-jacketed collection of Dickens, to the orange-spined Penguins, on down through school-approved sf writers like, say, Ursula Le Guin, to less respectable writers such as Robert E. Howard or Michael Moorcock, and then down to American comic books, perhaps the lowest of the low. (European comics were largely outside the scale I perceived; Japanese comics hadn’t yet really made the journey overseas.)

Time’s passed, and I’ve grown to appreciate some of those Penguin books; but, if I can now articulate what made them worthwhile, I can also articulate what made some of the sf and fantasy worthwhile as well. As a reader, as a lit student, as a critic and as a writer, I reached an understanding of at least some of the assumptions behind the hierarchy I half-perceived as a child. Some of them I discarded, some I came to accept, and in the end I developed a way of approaching books and literature which, however provisional and subject to further revision, serves at least me personally as a way to articulate what I find of value in a text.

My point is that this is something I had to work out for myself; that there was a consensus view of what constituted quality literature, in terms of subject matter and style, and that I had to teach myself about writing and the history of literature in order to understand how limited and historically unsupportable many of these assumptions were. I still see or hear, from time to time, statements people make which seem to suggest that they hold to some version of my childhood hierarchy. Consider the flap which arose when Kim Stanley Robinson suggested that some science fiction was worth consideration for the Booker Prize, the echoes of which debate can still occasionally be heard.

Obviously the devaluing of sf was and is a far from unanimous position. Fantasy’s long been accepted in mainstream contemporary literature under the name of magic realism, but recent years seem to have seen more and more writers become aware of the potential of both sf and fantasy. One thinks of Margaret Atwood (who wrote sf as far back as 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale), and Philip Roth’s alternate history The Plot Against America, and Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic The Road; also perhaps of Joyce Carol Oates’ Gothic novels, and the anthology she edited of H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction. Notable fantasist Salman Rushdie once observed that the basic joy of writing lies in making stuff up; in fantasising. Unfortunately, mainstream thought has been slow to follow him.

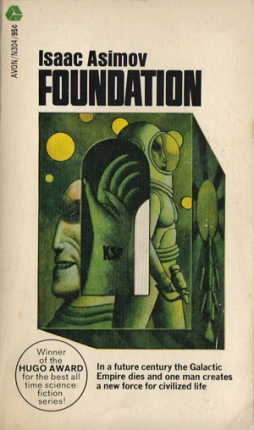

But now Penguin, they of the orange-spined paperbacks, have published a collection of Robert E. Howard’s fiction, introduced by John Clute (under the “Penguin Modern Classics” imprint, but still something I never thought I’d see). Everyman’s library has put out an edition of Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy. The Library of America has published three collections of Philip K. Dick’s work. Alice Sheldon, AKA James Tiptree, Jr., has been the subject of a well-received (and extensively reviewed) biography. Jack Vance was given a major profile in the New York Times Magazine.

But now Penguin, they of the orange-spined paperbacks, have published a collection of Robert E. Howard’s fiction, introduced by John Clute (under the “Penguin Modern Classics” imprint, but still something I never thought I’d see). Everyman’s library has put out an edition of Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy. The Library of America has published three collections of Philip K. Dick’s work. Alice Sheldon, AKA James Tiptree, Jr., has been the subject of a well-received (and extensively reviewed) biography. Jack Vance was given a major profile in the New York Times Magazine.

It seems to me that you don’t have to like all the writers mentioned in the previous two paragraphs (I don’t, but like some of each) to understand their importance. Too often I’ve seen discussions in which only one group — and sometimes it’s been one and sometimes the other — has been appreciated. And too often when the importance of both groups have been acknowledged, that importance has been viewed as being of two different kinds. But that’s exactly what seems to be changing now, if the things I’m seeing are representative. Granted that on the whole the aims, style, and approach of those two groups of writers are in fact fairly different, there now seems to be an increasing awareness that they’re at least excellent in the same medium, if in different idioms.

So at the same time science fiction and fantasy’s gained new critical acceptance by present writers, the past of the genre’s being re-examined as well. It seems as though canons are being formed, or re-formed. It may be true that Howard and Asimov and Dick are in no imminent danger of going out of print; but these editions make them more visible and more easily available to a mainstream audience. I suspect they may also make the books more attractive to professors looking to fill out a course syllabus, and more easily available to students.

It’s interesting to see how the packaging of the science fiction books is re-imagined for a different audience; how the books are presented from a new perspective. The cover of the Foundation trilogy doesn’t show any science-fictional scene, nor even the semi-abstract designs I remember from the editions of my youth, but instead a photo of Asimov. The emphasis is on the writer, and implicitly on his thought and his ideas, not on the story as such.

It’s interesting to see how the packaging of the science fiction books is re-imagined for a different audience; how the books are presented from a new perspective. The cover of the Foundation trilogy doesn’t show any science-fictional scene, nor even the semi-abstract designs I remember from the editions of my youth, but instead a photo of Asimov. The emphasis is on the writer, and implicitly on his thought and his ideas, not on the story as such.

On one level, this is nothing new — look at the different designs for different editions of John Crowley’s work, and you can clearly see which edition is aimed at which market. But one might worry that this re-imagining of the past of the science fiction genre means a rewriting of that past by people projecting their own concerns and priorities onto the fiction. If literary fiction and science fiction have tended to be evaluated by different criteria — language versus ideas, descriptive fidelity versus imaginative extrapolation — then the view of science fiction when seen through the lens of literary fiction might be distorted.

Realistically, though, this is something to be welcomed. The seeming distortion may actually be a needed correction. It may be that the importance of the genre will be demonstrated by the vitality of the debate between priorities. A canon isn’t a fixed list, or shouldn’t be; it’s an ongoing argument. It seems to me that different ideas of what good writing is, when set in counterpart to each other, produce a field of work richer and more varied than any fixed hierarchy can present. It allows those different ideas to be tested against each other, to enter into dialogue.

Realistically, though, this is something to be welcomed. The seeming distortion may actually be a needed correction. It may be that the importance of the genre will be demonstrated by the vitality of the debate between priorities. A canon isn’t a fixed list, or shouldn’t be; it’s an ongoing argument. It seems to me that different ideas of what good writing is, when set in counterpart to each other, produce a field of work richer and more varied than any fixed hierarchy can present. It allows those different ideas to be tested against each other, to enter into dialogue.

Above all, I think the whole process will make it easier for new writers to find predecessors whose imagination and aims have a resonance with their own. Canon formation is not the domain of academics, nor even of readers. A writer is kept alive by having an influence on other writers. If writing published as genre fiction is integrated into the broad field of literary texts, then the ideas and influence of that writing will find new ways to survive into the future.

Ideally, if the re-examination of genre writers continues, the understanding of science fiction and of fantasy will be enhanced and extended. But at the same time the understanding of literature will also be extended; its breadth, its variety, the many different ways in which it is possible to write a good book. The unarticulated hierarchy may still continue to exist, but hopefully it’ll be a little more complex, a little closer to reality. And maybe it’ll be that much easier for young readers in the future to work out their own sense of what makes good writing.

Ideally, if the re-examination of genre writers continues, the understanding of science fiction and of fantasy will be enhanced and extended. But at the same time the understanding of literature will also be extended; its breadth, its variety, the many different ways in which it is possible to write a good book. The unarticulated hierarchy may still continue to exist, but hopefully it’ll be a little more complex, a little closer to reality. And maybe it’ll be that much easier for young readers in the future to work out their own sense of what makes good writing.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

Penguin is great, but Howard deserves a Library of America edition. Lovecraft has one (deservedly — with a wonderful intro by Peter Straub). Howard was the stronger writer, being possessed of a more complete skill set and a better, or perhaps I should say more modern, sense of narrative.

Lovecraft was a bit of a one-trick pony, though his one trick was worthy of an entire career.

I didn’t know about the REH book by Pequin, but it does warm my heart to see it. Maybe finally he’ll get the respect due.

I’ve kinda wondered if I personally put REH on pedestol, just because I loved his stories so much and that those stories are what introduced me into fantasy, which is my favorite genre for books.

So when I see that a publisher which I’ve always associtated with the “classic” chosing his work for a collection, it makes me feel like maybe my personal taste isn’t just “pop-corn” reading after all. And that other people who are much more qualified and learned then myself consider his work to be worth reading.

I felt much the same way when the Library of America started publishing “genre” writers in their editions, but I have to admit to some mixed feelings too. I felt especially conflicted when they came out with their first Phillip K. Dick volume. Part of me though “It’s about time.” About time that such a fine writer was taken seriously by the literary establishment. But another part of me thought, “Screw the literary establishment and their much-too-late recognition.” Where were these people when Dick was eating dog food beacuse it was all he could afford? When Howard, Smith, and Lovecraft were working for a half a cent a word? Denying that such crap could have the least bit of merit, that’s where. So, while I am glad that that tide finally seems to be turning, I’ll keep my cheap, sleazy old paperback copies – they serve as a reminder that work of enduring value can be found in unlikely places, and that maybe I should look around in some of those unlikely places right now, because I can’t trust the Powers That Be to look there until we’re all long gone.

@emcgargle- Too true. I get what you are saying.

Plus, there’s the teen-aged rebel in me that has tendancy to embrace art, be it writing, music, movies,etc.., that isn’t qualified by the established authorities -whoever they are. But I have to say, I would love to see some professor of liturature doing a lecture on Conan. 🙂

I just wish Howard wouldn’t have killed himself. I wish he’d have hung around long enough to see the type of fiction he was writing become more popular in accepted. So that maybe he would have developed his stories just a little more for full-length novel format. He left us with a multidude of Conan adventures, but as much as I love Conan, Bran Mak Morn alway intrigued me the most. And we were left with little more then teasers of that character.

I’ve always thought if he’d have felt more accepted, and perhaps less alone, he’s work would have been all the better for it.

Kid, let me tell you about a literary fantasy that I’ve entertained for a long tome – I would give just about anything for an anthology of…well, I don’t know what to call them…fun house mirrors, maybe. I want a Henry James story written in the style of Robert E. Howard, and a Howard story done in the style of James. How about a Faulkner story as told by Lovecrsft, and a Lovecraft story done by Faulkner. A Hemingway/Clark Ashton Smith pairing would be wild…well, you get the idea!

[…] long known for its preservation of accepted, “literary” authors, has included him in its “Penguin Modern Classics” imprint. Critical works like The Dark Barbarian and The Barbaric Triumph are probably the best in what, […]