A Novel Superman

Media tie-in novels are common nowadays, and people have debated how good tie-in novels are and how good they can be. I don’t have any strong opinions, other than to note that a) the usual conditions under which tie-ins are written don’t seem encouraging; b) on the other hand, great books can be and have been written under much less encouraging conditions and much greater restrictions; and c) I’m really looking forward to reading Michael Moorcock’s Doctor Who novel.

Media tie-in novels are common nowadays, and people have debated how good tie-in novels are and how good they can be. I don’t have any strong opinions, other than to note that a) the usual conditions under which tie-ins are written don’t seem encouraging; b) on the other hand, great books can be and have been written under much less encouraging conditions and much greater restrictions; and c) I’m really looking forward to reading Michael Moorcock’s Doctor Who novel.

But I will say this: when the question of the quality of media tie-in novels arises, there are two books I think of as both tie-in novels and excellent fiction in their own right. There may be more, but these two have stuck with me from a young age, and every time I re-read them (as I do every few years), I find they’re still powerful and resonant work. The language is tight, terse and moving. The characters are strong. The world is well-conceived, feeling fresh and new.

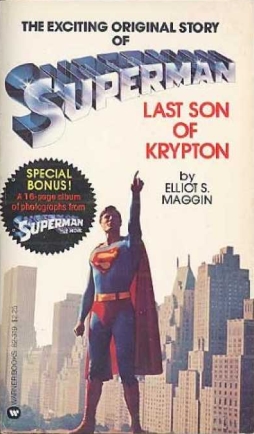

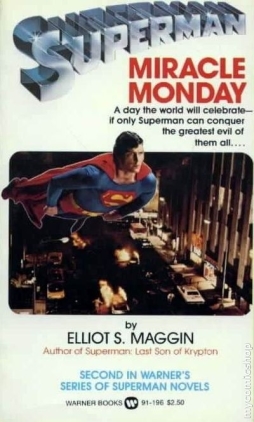

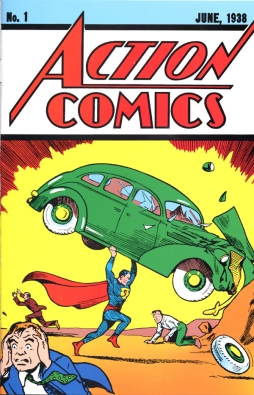

The books are Superman: Last Son of Krypton and Superman: Miracle Monday, by Elliot S! Maggin (follow the link to uncover the mystery of the exclamation point). Published to accompany the release of the first two Superman movies, the books have little to no connection with the movies as such, being instead original and utterly fascinating stories.

In the first book, Superman faces not only Lex Luthor but also a mysterious alien threat and a prophecy that spells his doom. In the second book, Superman has to deal with a demon named C.W. Saturn (whose name is an anagram of longtime Superman artist Curt Swan), “the agent of Hell on Earth”.

In the first book, Superman faces not only Lex Luthor but also a mysterious alien threat and a prophecy that spells his doom. In the second book, Superman has to deal with a demon named C.W. Saturn (whose name is an anagram of longtime Superman artist Curt Swan), “the agent of Hell on Earth”.

Maggin was one of the main writers of Superman comics in the 70s and into the 80s. He’d clearly thought about the character a lot. And it shows.

Maggin does something in these books that’s almost impossible: he allows you to easily suspend disbelief in Superman. Partly, that’s because he’s clearly thought out what it is to have the abilities that Superman does, and what it means to have that range of powers; his description of Superman’s sensory powers alone is often worth reading. But more importantly, he’s thought about why Superman is Superman, what it is that drives him to action, and what his sense of morality is like. He’s thought about the principles Superman has, and what sort of a mind he has, and why he believes what he does: “There were certain fundamentals … that he did not question—axioms at the bottom of his thoughts on any subject that approached his mind: that there was a right and a wrong in the Universe, and that value judgement was not very difficult to make.”

You can disagree with that statement; the point is that Maggin, in describing Superman and his actions, makes it believable as a basis for a hero’s deeds. He’s thought about right and wrong. He’s thought about how Superman works, as a character and as a concept.

You can disagree with that statement; the point is that Maggin, in describing Superman and his actions, makes it believable as a basis for a hero’s deeds. He’s thought about right and wrong. He’s thought about how Superman works, as a character and as a concept.

Generally, in his stories Maggin takes a good run at making Superman an actual science-fiction concept. He doesn’t bring in the wider DC universe, though bits and pieces of background do get mentioned — the Guardians of the Universe, the planet Rann, and so forth. He simply accepts that extraterrestrial life is common, and known to exist to the people of Earth, and the people of Earth have gone on their way in a sort of jaded half-awareness. How could they not know that aliens exist? There’s one in a blue costume flying around Metropolis. Superman’s changed the world; Maggin’s thought about that, too, rather than handwave it away. And that helps make the book feel like science fiction.

The writing style also feels like science fiction, for better or worse. It thrives on infodumps. They’re well-written, and often amusing; there’s a long digression in the first book on aliens and photocopiers that’s wryly funny, largely irrelevant to the plot, and utterly fascinating. In general, the books live in the memory as a series of bits and pieces, more than as a memorable narrative or a connected plot. That works, because the bits and pieces work; they bring out character, and establish a sense of wonder both wholly science fictional and utterly appropriate to the subject.

Consider the following sequence, from Miracle Monday. Superman’s followed a clue to a stage magician’s club, where a doorman doesn’t believe he’s Superman and refuses to let him in:

For a moment Superman considered telling the man the contents of his wallet, but he saw a friend inside who turned out to be a member of the club.

“Ray!” Superman called. “Ray, do you care to rescue this gentleman from an unforgiveable invasion of his privacy?”

Years ago, when he was fifteen years old, Clark Kent had read The Martian Chronicles. Clark was so impressed that Superboy flew off that afternoon to meet Ray Bradbury, the man who had written the book. What Superboy found was a man who had never flown in an airplane, who wrote stories about rocket ships, a Californian who did not know how to drive a car, a man relatively unconcerned with politics, who was, at least that day, obsessed with the idea of convincing Walt Disney to run for mayor of Los Angeles. Bradbury had a lifetime pass to Disneyland, which was where he and Superboy spent the rest of the day. Superboy had never been there before, and no one there believed he was really Superboy anyway. Children were more interested in getting the autograph of Mickey Mouse, and adults were confused by his presence since they thought that only Walt Disney characters paraded through these streets in costume.

Bradbury’s wife drove them to the amusement park in Anaheim. Bradbury utterly refused to allow the boy to fly him there, and neither of them had a driver’s license. Walt Disney, whom Superboy and Ray Bradbury found in his secret apartment overlooking the main entrance to Disneyland, again refused to run for mayor, but had his chauffeur drive the novelist home. Superboy flew back to the Smallville Public Library and read everything that Bradbury had ever had published.

So Bradbury gets Superman into the club, and promptly disappears from the story. The anecdote has no real point, plot-wise, other than to get Superman into a place he could have gotten into in half a hundred different ways. The point isn’t the plot; it’s the sense of wonder. It’s showing Superman as a teen being affected by a book, feeling that special sense of connection you get with an author — and then, because he’s Superboy, flying across the country to meet that author, and killing an afternoon with him at Disneyland, and meeting Walt Disney. It’s daydreaming, it’s wish-fulfillment, it’s utterly charming and so different from so many super-hero fantasies.

In fact, you could probably argue that the books are an inversion of what super-hero comics usually are, and certainly of what they have become. Most super-hero books are fantasies of power and violence; not these ones. Most super-hero books, especially these days, are concerned with plot and structure; not these books, not really. Most super-hero books focus on realism, on the limits of a hero’s capability, on the necessity of moral compromises; not these ones. The result is an unpredictable Silver Age feel to the books, but also, because Maggin is writing about a recognisably real world, an adult awareness, a wistful maturity.

At the same time, the books have many of the flaws of Silver and Bronze Age Superman stories, and arguably of Superman stories in general; Superman’s a passive character, led around, fed information, and generally driven by the plot to do what he has to do in order for the next bit of the story to unfold. And the plotting in general is very loose, even shambolic. Things happen, and then there’s a half-hearted climax that doesn’t really develop so much as appear and be easily resolved. Above all, there’s no real antagonist that provides a credible threat. Superman’s too super to really seem in danger at any point.

At the same time, the books have many of the flaws of Silver and Bronze Age Superman stories, and arguably of Superman stories in general; Superman’s a passive character, led around, fed information, and generally driven by the plot to do what he has to do in order for the next bit of the story to unfold. And the plotting in general is very loose, even shambolic. Things happen, and then there’s a half-hearted climax that doesn’t really develop so much as appear and be easily resolved. Above all, there’s no real antagonist that provides a credible threat. Superman’s too super to really seem in danger at any point.

Oddly, though, that helps the books. The use of violence is restrained, and there’s more thinking about how much force Superman really ought to use. It increases the stories’ crediblility, if only because there aren’t any improbable fistfights between beings who can shatter planets just by looking at them hard. And you don’t have the uncomfortable dichotomy of having Superman represent the higher angels of our nature, and also be somebody who easily uses violence on other people to attain his ends. That is, the character of Superman is not the character of a violent man (just look to Gotham City to see a contrasting hero figure); Maggin brings that out, while still making him effective, a competent and believable hero.

Conversely, Superman’s arch-enemy may be the most fascinating character in either book. In today’s comics, Lex Luthor’s usually portrayed as a clever but crooked industrialist; Maggin’s writing the old Luthor, though, the mad scientist. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a more convincing portrayal of a man vastly more intelligent than every other creature on the planet.

Experience had taught prison officials how unwise it was to allow their star inmate unsupervised access to tools or chemical materials of any kind. The only objects in Luthor’s cell after ten o’clock lights out were a legal pad and a ball-point pen. This was a foolish precaution, of course. The prison would hold Luthor for as long as Luthor chose to be held, and not a moment longer …

One night, in a loose moment, Luthor figured out how to melt the plastic cap of the pen, let a certain amount drip into the ink refill, extract a substance from the glue that bound the legal pad, wrap it all in half a sheet of yellow paper and make an explosive powerful enough to blast out a wall of his cell. Luthor would never do that, of course. If he did, the next time he was in jail the warden wouldn’t give him his pen and pad.

Neurotic, narcissistic, utterly brilliant, Lex lives in a state of constant frustration with the piddling monkey-brains all around him. We bore him. He’s isolated by his intellect; he’s a criminal just because it’s quicker, because he’s so far beyond the comprehension of everyone around him he can’t be bothered to justify himself.

He steals, sure, but mostly from institutions. He holds people for ransom — but we’re told that he’s never killed anyone. He employs people to evil ends, but he pays them well and gives them creative freedom. He has a certain code of ethics:

Luthor reminded himself of a song he’d once written which had a line that went: “to live outside the law you must be honest.” He’d slipped the lyrics to a young singer he met in a bar in Minnesota. The guy had a lousy voice and Luthor felt sorry for him at the time. When he heard the line again he didn’t recognise the song that surrounded it. He resolved, from then on, to be his own editor.

This depiction of Luthor actually makes for good drama. Rather than having one good man and one bad, these stories show two good and smart people who interest you and do unexpected things; and by circumstance and conviction and past history, they’re driven into conflict, with one holding a powerful grudge against the other. It’s considerably more morally complex than a standard story about a hero and a villain, and therefore more interesting than any other Superman-Luthor story I can ever remember reading; Maggin dares to make his villain a hero.

There is, nevertheless, a great contrast between Luthor and Superman in these books. It shows in any number of different ways. For example, Luthor’s so mind-bogglingly smart he keeps a score of alternate identities going almost as hobbies. He’s a genius-level conceptual artist named Jeremy McAfee, for example, whose artwork happens to be Luthor’s inventions, hidden in plain sight. He’s also an eccentric billionaire named Lucius D. Tommytown. And a brilliant doctor named David Skvrsky. He kills them off as needed, starts up new ones when required, and thinks nothing of being so many different people. Superman, on the other hand, has one alternate identity; but he loves it, and could not conceive of killing him off.

(Understand, this isn’t to say that in these books Clark Kent is Superman’s secret identity the way that, as is so often pointed out, Bruce Wayne is only Batman’s secret identity. It’s more complicated. Clark Kent of Smallville created the secret identity of Superboy, who grew into Superman, who created the secret identity of Clark Kent of Metropolis. Both are real; both created the other.)

(Understand, this isn’t to say that in these books Clark Kent is Superman’s secret identity the way that, as is so often pointed out, Bruce Wayne is only Batman’s secret identity. It’s more complicated. Clark Kent of Smallville created the secret identity of Superboy, who grew into Superman, who created the secret identity of Clark Kent of Metropolis. Both are real; both created the other.)

The first book unfolds with frequent flashbacks to the youth of Superman and Luthor, and we follow the two men, with the emphasis really on Luthor, as his genius manifests itself, as tragedy affects him. The structure’s clever, contrasting past and present, and suggesting that Luthor’s the real ‘hero’ of the book. Similarly, the second book flashes back to the past, showing Superboy’s growth to Superman, showing the worst nightmare of Pa Kent, showing the development of character over time.

In some ways, although Miracle Monday has a more compelling plot and a clever jigsaw-puzzle-like structure in which seemingly-unrelated elements slowly come together to suddenly produce a desperate situation, it’s actually a weaker book than Last Son of Krypton. The presence of another villain weakens the presence of Luthor, and the parallel between past and present doesn’t feel as well-managed. The sense of a threat is stronger, but when a significant blow is given to Superman late in the book, he recovers from it too easily — though admittedly in a beautifully-written and cleverly-conceived passage.

The first book, on the other hand, seems to be what the first movie should have been. It introduces Superman and his world, it establishes Luthor, and it brings Superman out into space with a sense of awe and wonder. There’s a villain, and a plot — and the plot, from a certain point of view, is actually the same plot as Luthor was given in the movie, but conceived on an interstellar scale, which feels more appropriate to the super-hero world. There’s a sense of grandeur to it that the movie couldn’t catch when it mattered most.

Maggin’s Superman novels were published in 1978 and 1981; they came before the great wave of revisionist superhero books, before Watchmen and Dark Knight and even Squadron Supreme. Those books, in their different ways, tried to ask ‘what if super-heroes were real?’ Answering the question seemed to suggest that most of the characteristic elements of the super-hero had to be jettisoned or altered, from costume to morality. Maggin’s novels, though, take what seems to me to be a more interesting approach. They seem to ask: “Given that the super-hero exists as we know it, why does it exist the way it does, and what follows from it?”

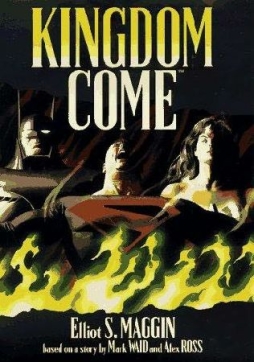

But what, then, does Maggin’s work have to say to the current wave of revisionist hero stories? That question, oddly, was answered about a dozen years ago, when Maggin wrote the novelization of Kingdom Come, a prominent miniseries by writer Mark Waid and artist Alex Ross.

But what, then, does Maggin’s work have to say to the current wave of revisionist hero stories? That question, oddly, was answered about a dozen years ago, when Maggin wrote the novelization of Kingdom Come, a prominent miniseries by writer Mark Waid and artist Alex Ross.

The novelization of Kingdom Come is a fascinating and very nearly successful attempt at making chicken salad out of something that really is not chicken salad even slightly. The comic is a pretentious, thematically incoherent, poorly-structured story set in a near future when Superman retreated from the world to take up farming in the Antarctic; in his absence, superhumans lost all moral compass. The story follows his return to the world, and how this leads to conflict between various poorly-defined factions, eventually reaching a nonsensical climax that seems to settle nothing.

Maggin’s novelization is a remarkable use of substandard source material. He adds and reorders scenes to create great character moments — notably, a brief chapter showing Batman gradually fixing the ruins of Wayne manor and slowly realising that he’s happy. Indeed, Maggin builds coherent character development over the course of the story which was difficult to discern in the original work.

Maggin goes so far as to almost make one of the comic’s terrible structural choices effective; in the original, the story is told through the eyes of a pastor named Norman McCay, who is shown events by a supernatural entity called the Spectre, allegedly so that McCay can help the Spectre deliver vengeance upon those guilty of a great crime to come. In fact, no vengeance is ever delivered, and McCay’s effect on the narrative is minimal. Maggin takes the extraneous pastor, and makes him work. McCay becomes a real person, whereas in the comic he stands around asking questions and spouting Bible verses. He becomes a thematic centre; we watch hope and faith be reborn in him, we watch him come to find meaning in events, and therefore through McCay Maggin almost makes those events meaningful. It’s as much as any writer could do, I think.

And Superman? Maggin almost makes Superman’s significance as a moral guiding light credible. It’s an article of faith among many fans, and many comics writers, that Superman has that weight of credibility, that he is the hero of heroes; usually stories that insist on this point don’t work, though. Very often I think most comics writers don’t have a clear enough idea of what a hero is, or in what heroism consists. And even when they do, I think Superman’s heroism is rarely dramatically developed or demonstrated in the course of a work.

And Superman? Maggin almost makes Superman’s significance as a moral guiding light credible. It’s an article of faith among many fans, and many comics writers, that Superman has that weight of credibility, that he is the hero of heroes; usually stories that insist on this point don’t work, though. Very often I think most comics writers don’t have a clear enough idea of what a hero is, or in what heroism consists. And even when they do, I think Superman’s heroism is rarely dramatically developed or demonstrated in the course of a work.

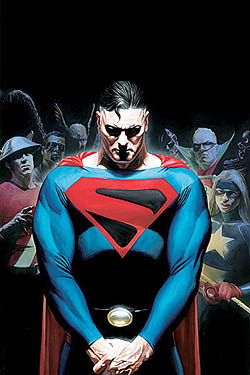

The Kingdom Come comic’s a good example. What is it about Superman that makes him special? What things has he done that mark him out as gifted above all other heroes? Reading the comic, I have no idea. In the novelization, on the other hand, Maggin makes the case for Superman’s significance. Rather than list off triumphs or great deeds, though, he shows it by describing who Superman is as a person, and by examining the way other people react to him. The grasp and detail of the character work’s strong enough that Superman comes into focus as a hero in a way that rarely happens in comics.

On the one hand, the difference between what Maggin does here and what he did in the earlier novels is that here he’s working with a story that forces Superman to make some questionable choices and indeed to appear to be a fool in several places — notably, after making several speeches about how he and his re-formed Justice League would put an end to the widespread violence of the new generation of superhumans, he’s shocked by Wonder Woman’s idea that they build a prison to hold the bad guys. On the other, Maggin gets the chance here to contrast his wholly remarkable hero with other heroes, and indicate the difference between them. What makes him so different from all other heroes? Maggin answers that question, not with any easy proclamation, but by the much harder task of actually showing him being a hero, and being in the company of heroes, and standing out not because of some quality of his deeds but simply by being who he is.

Kingdom Come stands with Superman: Last Son of Krypton and Superman: Miracle Monday as being implicitly a book about what it means to be a hero. I don’t think it’s as good as the first two, due largely to the source material it had to work with. The character of Superman, and the universe around him, are both very different; and there’s almost no comparison between Lex Luthor here and the fascinating Lex of the earlier books. Still, the three novels are all of them worth reading, if for different reasons.

Maggin’s Superman prose fiction can be found online. Here is Superman: Last Son of Krypton. Here is Miracle Monday. And then here are two other short pieces as well: “Luthor’s Gift” is a story that ties up the relation between Superman and Luthor from the novels (though you don’t really need to have read the books to enjoy it, the conception of the characters does follow on directly from the novels, and serves as a satisfying coda). Starwinds Howl is a novella about one of the minor characters in the world of Superman; again, it’s a satisfying piece of science fiction and speculation about superdense planets, probability-manipulating pilots — and the tie between men and dogs.

Maggin’s Superman prose fiction can be found online. Here is Superman: Last Son of Krypton. Here is Miracle Monday. And then here are two other short pieces as well: “Luthor’s Gift” is a story that ties up the relation between Superman and Luthor from the novels (though you don’t really need to have read the books to enjoy it, the conception of the characters does follow on directly from the novels, and serves as a satisfying coda). Starwinds Howl is a novella about one of the minor characters in the world of Superman; again, it’s a satisfying piece of science fiction and speculation about superdense planets, probability-manipulating pilots — and the tie between men and dogs.

Everybody has their own favorite Superman story. In the seventy-plus years the character’s been around, he’s been through a host of different guises, and appeared in some excellent tales. For me, though, Maggin’s novels are the best Superman stories I’ve ever read; better than Alan Moore’s Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, better than Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman. I haven’t found a story that makes Superman so fantastic, and at the same time so real. I haven’t found a Superman story that explains why he’s the world’s greatest hero as convincingly as these ones. I don’t particularly expect to. I’m just thankful I had the chance to read them.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.</em

[…] I can watch episodes of the Superman animated series episodes Justice League and […]