A Writing Lesson about Pettiness from Poe

In his famous essay “The Simple Art of Murder” (1944) noir author Raymond Chandler discusses the separation between loftiness of subject in writing and its literary success:

In his famous essay “The Simple Art of Murder” (1944) noir author Raymond Chandler discusses the separation between loftiness of subject in writing and its literary success:

Other things being equal, which they never are, a more powerful theme will provoke a more powerful performance. Yet some very dull books have been written about God, and some very fine ones about how to make a living and stay fairly honest. It is always a matter of who writers the stuff, and what he has in him to write with. As for literature of expression and literature of escape, this is critics’ jargon, a use of abstract words as if they had absolute meanings. Everything written with vitality expresses that vitality; there are no dull subjects, only dull minds.

Chandler’s thesis here also applies to an author’s intention as well as his or her subject matter. Most of us can safely say that anyone who sets out to write “The Great American Novel” or “The National Epic of [Insert Nation Here]” will inevitably fail at that task. On the other hand, an author might produce an enduring work of literature if he or she simply sets out to jab some pins into another author over a petty feud. That may sound dull-minded, like a schoolyard tussle over who was next in line for handball, but if the mind behind it isn’t actually dull, then the result could be a masterpiece.

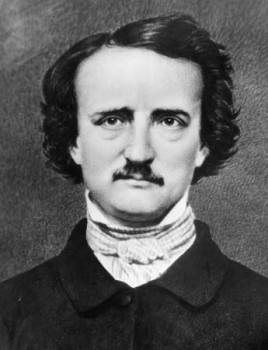

Case in point: “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe. If you haven’t read this 1846 tale of revenge in Italy, than you must have been home sick from school that day in sixth grade.

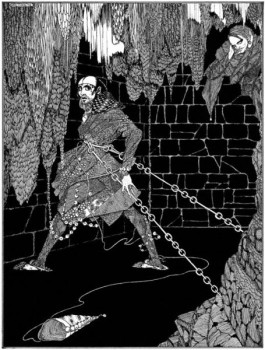

“The Cask of Amontillado” is a 2400-word tale told in first-person about how nobleman Montresor punishes another nobleman, Fortunato, for an unspecified “insult” that came about after an even less specified “thousand injuries.” Montresor lures a drunken Fortunato away from a carnival and down into the catacombs of his family estate on the promise that he has discovered what may be a barrel (or “pipe”) of Amontillado, a kind of Spanish sherry that gets its name from the Montilla region, and wishes Forunato’s self-claimed expertise on the matter. Once Montresor has Fortunato down in the catacombs, he chains down the sodden man in a niche a proceeds to wall him up alive with mortar and trowel. Montresor rises a bit from his stupor as death seals him in, lucid enough to shout the story’s most famous line: “For the love of God, Montresor!” After a moment’s hesitation (“on account of the dampness of the catacombs,” he informs us) Montresor slides in the last brick and leaves Fortunato entombed behind masonry and a pile of bones. “For the half of a century no mortal has touched them. In pace requiescat!”

The story is a classic of the Gothic tale, using revenge, an Italian setting, a subterranean tomb, medieval trappings (such as the motley that Fortunato is wearing), and madness. It also characterizes Poe’s development of the short story and use of every word to propel the narrative forward.

But according to modern Edgar Allan Poe scholars, the origin of “The Cask of Amontillado” is a feud between Poe and author, poet, and politician Thomas Dunn English (1819–1902). Originally friends, the two fell out and even once came to blows. They started to swap caricatures of each other in the press, leading Poe to successfully sue English for libel, winning the award of $326.48—probably more than Poe got paid for anything else in his ragged life. English fired back with a revenge-themed novel, 1844, or, the Power of the S.F. which includes a drunk, mendacious, and abusive character named Maramduke Hammerhead, who authored the famous piece The Black Crow.

But according to modern Edgar Allan Poe scholars, the origin of “The Cask of Amontillado” is a feud between Poe and author, poet, and politician Thomas Dunn English (1819–1902). Originally friends, the two fell out and even once came to blows. They started to swap caricatures of each other in the press, leading Poe to successfully sue English for libel, winning the award of $326.48—probably more than Poe got paid for anything else in his ragged life. English fired back with a revenge-themed novel, 1844, or, the Power of the S.F. which includes a drunk, mendacious, and abusive character named Maramduke Hammerhead, who authored the famous piece The Black Crow.

Poe’s response was appropriate to his own theory of composition: he slashed back with a mere 2400 bricks of finely chosen words, turning Thomas Dunn English into Fortunato and copying masonic images from 1844 as well as the symbol of the hawk and the snake that he placed onto Montresor’s coat of arms. More than anything else, it was the form of the work, a short story, that was a rebuttal to English’s larger tome.

Both men are long dead, but it is easy to tell who won the fight in the long run: Walk into your local chain bookstore and see how many books you can find by Thomas Dunn English and Edgar Allan Poe. Compare.

There are definitely some sharp barbs in the story against English. For example, Fortunato claims to be a connoisseur of wines, yet he repeatedly berates another connoisseur, Luchesi, for being unable to tell Amontillado from sherry. Well, Amontillado is sherry, you nitwit. I can feel the literary critic Edgar Allan Poe violently kicking English in the head each time Fortunato, dressed up like a Fool with silly jangling bells, makes this stupid assertion. Today, he’d be saying: “Hah, Luchesi cannot tell Guinness from beer!”

However, none of this literary bickering really matters in the long view with regard to the effect of “The Cask of Amontillado.” Knowing the background of the feud that created the story only adds a certain academic interest, and in fact when I learned about the origin of the work, it only made me appreciate more how incidental it all is to why the story is so superb. “The Cask of Amontillado” is a brilliant work of short fiction regardless of why Poe wrote it, and I’m certain Poe knew it would work on its own; he only cared that his foe knew the background and caught the swipes. Poe was writing work for public consumption and popular tastes (it was published in Godey’s Lady’s Book, the leading monthly magazine of the day) and he succeeded.

As far as literary analysis of “The Cask of Amontillado” goes, what makes the story fascinating is not why Poe wrote it, but how he wrote it. It is a narrative that manages to satisfy within its limited boundaries of a few pages, but leaves open many topics for discussion, such as whether Montresor is an unreliable narrator, possibly insane; the issue of what Fortunato did to Montresor in the first place that got him so enraged—if he indeed did anything; the psychology of Montresor expressed through his language and thoughts; the story as part of the Gothic tradition; and Poe’s expert use of the short story narrative. (I’ve always felt that “The Cask of Amontillado” is a perfect example of a writer entering the story at the exact right time, dispensing with all unnecessary set-up and background, and then letting the minute actions and specific words of the characters reveal everything to us through implication.)

As far as literary analysis of “The Cask of Amontillado” goes, what makes the story fascinating is not why Poe wrote it, but how he wrote it. It is a narrative that manages to satisfy within its limited boundaries of a few pages, but leaves open many topics for discussion, such as whether Montresor is an unreliable narrator, possibly insane; the issue of what Fortunato did to Montresor in the first place that got him so enraged—if he indeed did anything; the psychology of Montresor expressed through his language and thoughts; the story as part of the Gothic tradition; and Poe’s expert use of the short story narrative. (I’ve always felt that “The Cask of Amontillado” is a perfect example of a writer entering the story at the exact right time, dispensing with all unnecessary set-up and background, and then letting the minute actions and specific words of the characters reveal everything to us through implication.)

All this came about because Poe was unhappy at another writer for making fun of him in a windy book. Greatness of intention doesn’t assure greatness of result; pettiness of intention doesn’t assure pettiness of result.

I don’t want to suggest that an author should indulge in every tale of anger toward a specific target that comes to mind. If each impulse toward revenge were set down on the page for intended publication, we would have a national literature that consists solely of diatribes against ex-girlfriends and boyfriends. (Although imagining a world where such as thing has occurred is intriguing. . . .) For example of this backfiring, see how M. Night Shyamalan chose to attack film critics with The Lady in the Water. But, other things being equal, which they never are, avoiding all petty desires as an impulse to write is also a mistake. Writing with vitality is the key here, and if knocking the stuffing out of a former boss in some weird werewolf-zombie futuristic apocalypse piece is what gets your keyboard humming or your pen scratching, then go for it. In the rewrites, you’ll probably tone down the more specific points of your fury anyway, but the general fury will stay and that’s to the good. Your next impulse (“I would like to write something that will sell.”) will probably be a more positive one.

Anyway, I must leave you now. There’s an old bully from elementary school poking around in my basement who is just begging to get walled up alive. “For the love of God, Harvey!”