Fantomas: An Introduction

Fantomas is criminally unknown in the United States. Only seven of the original 43 classic French pulp novels are currently in print in English. The series is unique in its successful blend of black comedy and absurdist humor within the traditional murder mystery genre.

Fantomas is criminally unknown in the United States. Only seven of the original 43 classic French pulp novels are currently in print in English. The series is unique in its successful blend of black comedy and absurdist humor within the traditional murder mystery genre.

Fantomas himself is a criminal anarchist who robs and murders for the sheer joy of creating chaos. While the murders are frequently described in surprisingly grisly detail for their day, they are quickly followed by delightfully sublime escapes or revelations handled with such a deftly light touch that it is impossible not to find the villainous character fun in spite of his many crimes.

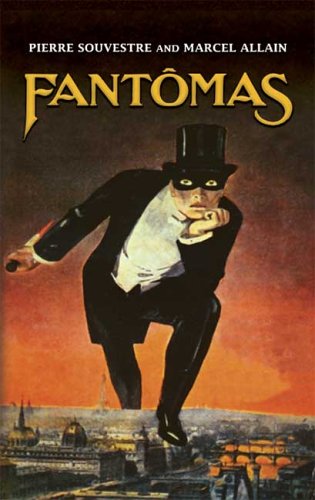

Fantomas made his debut in the 1911 novel, Fantomas. The book was an instant sensation whose appeal transcended all barriers of French society. The avant-garde adopted the character as one of their own. Inspired by Gino Sterace’s lurid cover art for the first book, surrealists such as Rene Magritte and Juan Gris, composer Kurt Weil, and poets such as Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob soon incorporated the character in their work.

Fantomas’ appeal to the art world was as strong as the popularity of the books among the working class. The character’s centennial next year will be marked with celebrations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia in an effort to bring greater recognition to the character and its impact on 20th Century art.

The books were the work of two journalists, Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain. Although creating dime novels that recalled the penny dreadfuls of the past, the Fantomas series is far more than mere hack work. While the two men would collaborate on a basic outline, their habit was to write alternating chapters. They completed 32 Fantomas novels in just two years and enjoyed winding the other up by leaving the heroes or their villain in impossible situations. Sometimes the resolutions were brilliant, other times merely brilliantly funny. Rarely does the pace slacken in these books. Most maintain a sustained delirium that is easily addictive.

The books were the work of two journalists, Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain. Although creating dime novels that recalled the penny dreadfuls of the past, the Fantomas series is far more than mere hack work. While the two men would collaborate on a basic outline, their habit was to write alternating chapters. They completed 32 Fantomas novels in just two years and enjoyed winding the other up by leaving the heroes or their villain in impossible situations. Sometimes the resolutions were brilliant, other times merely brilliantly funny. Rarely does the pace slacken in these books. Most maintain a sustained delirium that is easily addictive.

The closest counterparts to Fantomas that Americans would be familiar with would be Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta or Vincent Price’s two cult classic Dr. Phibes films of the early 1970’s. Fantomas’ true identity appears to be an unlikable rogue named Gurn, but he maintains so many alternate lives that the mind reels. The heroes of the books, Inspector Juve and the tabloid journalist Fandor similarly possess convoluted histories and so many multiple identities and disguises that one can never be entirely certain of anything short of the fact that the authors were brilliant farceurs steering the reader from one misadventure to the next.

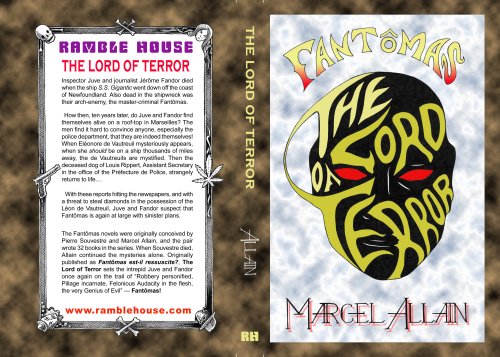

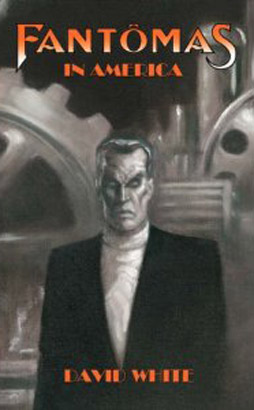

While the initial series ended on the eve of the First World War with Fantomas, Juve and Fandor seemingly perishing aboard the Titanic, Marcel Allain chose to revive the series in 1925 (after Pierre Souvestre’s death and after Allain had married Souvestre’s widow). Allain completed a further 11 books on his own sporadically over the next 18 years. David Lee White became the first true Fantomas continuation author with his brilliant Fantomas in America in 2007.

While the initial series ended on the eve of the First World War with Fantomas, Juve and Fandor seemingly perishing aboard the Titanic, Marcel Allain chose to revive the series in 1925 (after Pierre Souvestre’s death and after Allain had married Souvestre’s widow). Allain completed a further 11 books on his own sporadically over the next 18 years. David Lee White became the first true Fantomas continuation author with his brilliant Fantomas in America in 2007.

Dover and Penguin both offer rival translations of the initial novel. My own preference is for the Dover edition as it includes the bloodied knife in Fantomas’ right hand in Sterace’s cover art whereas the Penguin edition airbrushes the offending weapon out of the picture. David Lee White’s own imprint, Beltham House (named for Gurn’s star-crossed lover, Lady Beltham who never ceases loving Fantomas even after he has murdered her husband in the very first book) has reprinted the first sequel, The Exploits of Juve (also published as The Silent Executioner by other hands in a slightly different translation) as well as the fourth and fifth books in the series, A Nest of Spies and A Royal Prisoner, respectively.

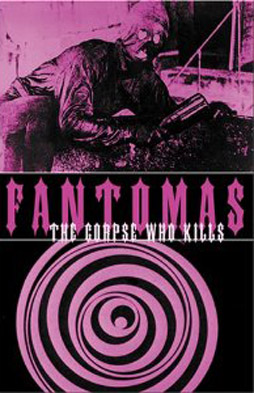

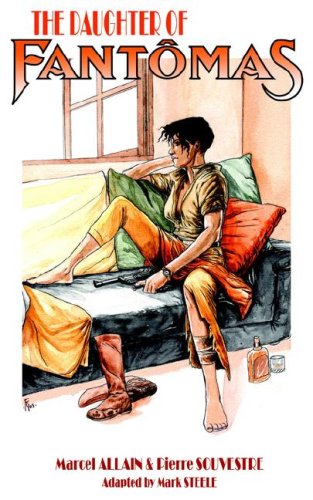

Solar Books offers an excellent translation of the third book as The Corpse Who Kills (rival imprints offer the title in a different translation as Messengers of Evil). Black Coat Press published the only English-language translation of the eighth book in the series, Daughter of Fantomas in addition to David Lee White’s previously mentioned continuation novel a few years back. Tucker Finlayson’s amusingly-named Ramble House imprint offers a rare reprint of the first of Marcel Allain’s revived series with the 33rd Fantomas title, The Lord of Terror, first published in 1925.

Solar Books offers an excellent translation of the third book as The Corpse Who Kills (rival imprints offer the title in a different translation as Messengers of Evil). Black Coat Press published the only English-language translation of the eighth book in the series, Daughter of Fantomas in addition to David Lee White’s previously mentioned continuation novel a few years back. Tucker Finlayson’s amusingly-named Ramble House imprint offers a rare reprint of the first of Marcel Allain’s revived series with the 33rd Fantomas title, The Lord of Terror, first published in 1925.

The centennial of the character will bring reprints of the sixth and seventh titles in the series, The Long Arm of Fantomas and Slippery as Sin late next year from Beltham House. 2012 will see the first English translations of the last two Pierre Souvestre-Marcel Allain titles (numbers 31 and 32 in the series, respectively) by Black Coat Press who will combine the books in an omnibus edition entitled The Death of Fantomas.

The series is a rare one that does not fall off in quality after the first few titles as the authors’ ingenuity and uniquely French spirit and humor keep the proceedings fresh and funny throughout its long run. As is often the case with black humor, the books are frequently merciless in their skewering of church and state. Class distinctions are another regular target. Souvestre and Allain were possessed of sharp wits and rarely failed to hit their marks. David Lee White, to his credit, kept up this tradition admirably and leaves readers hungry for his promised sequel.

Fantomas proved to be my introduction to the rich history of French crime fiction that also includes Paul Feval’s epic crime family series, The Black Coats and his delightful precursor to Fantomas, John Devil as well as Emile Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq, an influence on both Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal Arsene Lupin mysteries and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s immortal, Sherlock Holmes. Fantomas’ centennial is the perfect time for new readers to jump on board and savor the unique delights of the twisted, fiendishly funny exploits of the villain no cell or grave can ever hold for long. Like the finest wines, a sampling will lead one to savor the taste until all but the strongest will succumb and drink deep until the point of excess. Where Fantomas is concerned, moderation is not recommended.

Fantomas proved to be my introduction to the rich history of French crime fiction that also includes Paul Feval’s epic crime family series, The Black Coats and his delightful precursor to Fantomas, John Devil as well as Emile Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq, an influence on both Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal Arsene Lupin mysteries and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s immortal, Sherlock Holmes. Fantomas’ centennial is the perfect time for new readers to jump on board and savor the unique delights of the twisted, fiendishly funny exploits of the villain no cell or grave can ever hold for long. Like the finest wines, a sampling will lead one to savor the taste until all but the strongest will succumb and drink deep until the point of excess. Where Fantomas is concerned, moderation is not recommended.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). He is currently working on a sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu as well as The Occult Case Book of Sherlock Holmes. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com

Very fun!

Is “Mack the Knife” an incarnation of Fantomas?

If so, what a precedent!

Thank you for this article!

Glad that you appreciated it. I’ll leave the Mack the Knife identity issue to an enterprising Wold Newtonian to resolve.

Jean-Marc L’officier, editor and publisher at Black Coat Press emailed me with the following:

“I need to correct a small fact: bizarrely the cover of #1 was NOT by Gino Starace; for a reason I can’t fathom it was taken from an ad for some kind of medecine with a mask and a bloody dagger replacing a pill bottle spreading pills over Paris hastily added. The artist is unknown to this day. The airbrushed version sans dagger is somewhat authentic as well as it was that used by Feuillade for the first Fantomas movie serial.

“Souvestre & Allain had written a few pre-Fantômas novels before, sharing some themes and the character of the Investigating Magistrate, and actually recycled their plots into Fantômas novels (Le Mort Qui Tue is a case in point). Also note that towards the end there’s little doubt they used ghostwriters. The penultimate novel La Corde de Chanvre which I’ll be translating soon is undoubtedly the work of someone else.”

Mac the Knife from the Threepenny Opera? That’s an adaptation of John Gay’s 18th c. The Beggar’s Opera. So…influenced, maybe?

Though Brecht wrote the book for it, not Kurt Weill, so maybe not. But maybe they read the same books! Who knows?

Pretty sure that Claire was kidding about “Mack the Knife” being a relative. The Weill piece was “The Ballad of Fantomas.” Here’s the info from a great Fantomas website and online resource: http://www.fantomas-lives.com/

“And Robert Desnos’s 25-stanza poem La Complainte de Fantômas (The Ballad of Fantômas), quoted above, was dramatized and broadcast throughout France and Belgium in November 1933. According to Daniel Gerould’s Guillotine: Its Legend & Lore (New York: Blast Books, 1992) it was “a monumental production with a cast of over one hundred, including cabaret and music hall artists, buskers, accordionists, whistlers, and clowns, as well as opera singers and recitalists. Organized by Le Petit Journal to publicize the paper’s new serial ‘Could It Be Fantômas?’ by Marcel Allain, this celebration of the Emperor Of Crime created an unlikely meeting of artistic talents. Antonin Artaud directed, Kurt Weill composed the music, and Cuban musicologist and author Alejo Carpentier, who twenty years later would write the extraordinary guillotine novel Explosion In A Cathedral, conducted the ensemble.” The poem closed with an image taken from the original book cover:

His immense shadow spreads out

Over Paris and the world,

What is this grey eyed specter

Who surges through the silence?

Might it be you, Fantômas,

Prowling on the high rooftops?”

Ah, I wasn’t sure. I actually had a much *more* pedantic comment (if you can believe that) queued up before I realized it might be a joke.

[…] first appeared in 1857, but (so far as I can tell) only had the one identity. The villainous Fantômas and the heroic Nyctalope first appeared (separately) in 1911. Zorro was introduced in 1919, The […]