The Book Fair

The McGill book fair is the largest English-language used book sale in Montreal. It’s been held for decades, every October, on the second Wednesday and Thursday after Thanksgiving (which in Canada is on the second Monday in October). Every year an eclectic mix of thousands of books are sold, helping to raise money for scholarships.

The McGill book fair is the largest English-language used book sale in Montreal. It’s been held for decades, every October, on the second Wednesday and Thursday after Thanksgiving (which in Canada is on the second Monday in October). Every year an eclectic mix of thousands of books are sold, helping to raise money for scholarships.

I’ve been coming to the sale for about a dozen years. I’ve found novels by Lord Dunsany, a biography of C.S. Lewis, a book about Hypatia of Alexandria, a Dennis Wheatley omnibus, Fighting Fantasy Gamebooks, Paul Park’s Celestis, a volume combining Bede’s Ecclesiastical History with The Anglo Saxon Chronicle, collections of poetry by John Clare and Francois Villon and Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Southey and Don Marquis, a graphic novel by Posy Simmonds — and all of these (along with books by Neal Stephenson, Tad Williams, and T.H. White) in just one year, 2008, when I bought a total of 65 books for $161.

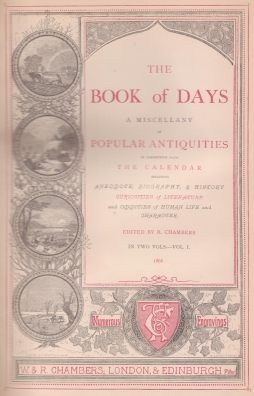

It has to be said, though, that hauls like that have been the exception lately. When I started coming to the sale, and for years thereafter, it was the best bargain running; tons of books were being sold for a quarter or fifty cents. Hardbacks might be only a couple of dollars. Older and more obviously rare books cost more, but were still quite reasonable; I bought a two-volume set of Chambers’ Book of Days, a massive and eccentric Victorian reference work from the 1860s, for fifty dollars.

It has to be said, though, that hauls like that have been the exception lately. When I started coming to the sale, and for years thereafter, it was the best bargain running; tons of books were being sold for a quarter or fifty cents. Hardbacks might be only a couple of dollars. Older and more obviously rare books cost more, but were still quite reasonable; I bought a two-volume set of Chambers’ Book of Days, a massive and eccentric Victorian reference work from the 1860s, for fifty dollars.

Lately, prices have been going up. They’re still good, of course, but it used to be you could go to the fair and build up a library of English classics for almost pennies. That’s more difficult now. And the selection’s been less diverse, with fewer unpredictable treasures. In years past you could almost count on finding overlooked writers of bygone decades, the Dunsanys and Chestertons and Mervyn Peakes; I once, on a whim, bought an epic poem about the English folkloric figure Wayland Smith, written by a woman in the 1920s of whom even the internet can tell me nothing. But lately that sort of material’s been drying up. Last year I bought only thirty-five books, admittedly for just $70.

There’s certainly still a long line-up to get in when the sale opens on the first day. Fewer people than there used to be, but several dozen, at least; “You don’t see this many people turn out for a used computer sale,” as somebody joked last year. I’ve learned by this point that my best approach is to arrive at 7 AM for the 9 AM opening; I’m near the head of the line without sacrificing too much sleep.

(In fact, one of the best tips I’ve ever picked up on line-waiting I overheard here: if you’re going to be waiting in line, always arrive at five minutes to the hour. Most people aim to get to a line “somewhere around” a given o’clock, which usually means they arrive at the line five or ten minutes after the hour. So if you’re at the line five minutes before the hour, you’re ahead of all of them.)

There’s a certain identity to the line, too, shaped by the presence of used-book dealers, professionals, some of them from out of town. You can hear stories, and chat about what sort of luck you’ll have this year. The funny thing is that different people may be looking for entirely different things, but it seems as though irrespective of what they’re looking for, some years the fair’s good and some years it’s dry. I talk with some Toronto dealers about the sales in their city; there’s three annual sales the size of this one, they tell me, and people line up at 6 in the morning for a sale that begins at 4 in the afternoon. And when it begins? “It’s like dropping a cow into the Amazon,” I’m told.

The McGill sale takes place in the Redpath Building, an old pseudo-gothic limestone hall. The sale’s on two levels; history, English literature, philosophy, and some general fiction’s all upstairs, and that’s where I’ve had the most luck over the years. Besides, the upstairs section has a nicer feel. The lower floor’s cramped; small rooms, holding textbooks and art books and a few older books, plus a long table in a hallway with children’s books and mass-market paperbacks. It’s cramped upstairs, too, but that’s only because of the number of tables and books jammed into the fair’s high hall. There’s a dark wooden hammer-beam ceiling, and portraits on the walls looking down on the melee below.

(Thanks to the internet, you can see at right a picture of the hall from more than a hundred years ago. The windows and fireplace on the right side are gone. The tables are similar to what you find in the sale, but imagine single long tables where you see pairs together. The bookshelves also have been replaced by tables. Imagine all these tables filled with books; imagine cardboard boxes of books under the table; and imagine the spaces between the tables filled with herds of browsing book-buyers.)

(Thanks to the internet, you can see at right a picture of the hall from more than a hundred years ago. The windows and fireplace on the right side are gone. The tables are similar to what you find in the sale, but imagine single long tables where you see pairs together. The bookshelves also have been replaced by tables. Imagine all these tables filled with books; imagine cardboard boxes of books under the table; and imagine the spaces between the tables filled with herds of browsing book-buyers.)

At 9 the doors open and I go in. I grab an empty cardboard box from a stack nearby, so I have something to hold the books I find, and hit one of the tables of English literature. At first glance, it’s disappointing. The prices, scribbled in pencil on the first page, are higher than in past years; some books even have notes under the price, reporting how much more the book sells for on the internet. I’ve never seen that before at this sale. I’m reminded of a conversation I had in line with one of the Toronto dealers, who went to a sale and found a book with a printout of a listing from online bookseller hub AbeBooks justifying the asking price; the listing was his own, for another copy of the same edition. “I wanted to tell them, don’t listen to that guy,” he said. “That guy’s an idiot!”

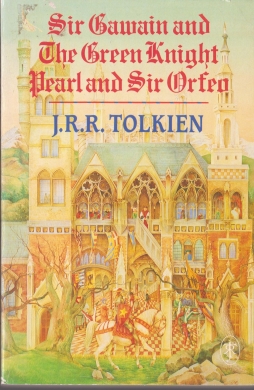

Prices aside, I don’t have much luck. I make a few finds; a copy of Tolkien’s translation of Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo is nice, and so is finding a translation of Goethe’s Elective Affinities (here rendered as Kindred by Choice). I find a couple of books by Iris Murdoch, whose fiction I’m picking up when I can. But most of the books I get are for my brother’s newborn daughter, investments against the next years of her life: Puck of Pook’s Hill, the complete Sherlock Holmes, Grimm’s Fairy Tales. But then Grace arrives: “They’ve got the science fiction up here this year,” she tells me.

Prices aside, I don’t have much luck. I make a few finds; a copy of Tolkien’s translation of Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo is nice, and so is finding a translation of Goethe’s Elective Affinities (here rendered as Kindred by Choice). I find a couple of books by Iris Murdoch, whose fiction I’m picking up when I can. But most of the books I get are for my brother’s newborn daughter, investments against the next years of her life: Puck of Pook’s Hill, the complete Sherlock Holmes, Grimm’s Fairy Tales. But then Grace arrives: “They’ve got the science fiction up here this year,” she tells me.

Four years ago I came to the fair, and, as I usually do, looked over the books on the upper floor before descending to the lower floor, where the fair usually keeps children’s books, older books, textbooks, and, on a long L-shaped table, all sorts of mass-market paperbacks. Mystery; romance; science-fiction and fantasy. As on the upper floor, more boxes of books were underneath the table.

I joined the throng looking over the table; and spotted a three-volume set of Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy just as a delicate hand reached in to pick it up to look over. I already had a copy of the books, myself; the woman who’d taken them tucked them under her arm. She was directly ahead of me in the line moving left to right along the table, and this meant that as we went on we were also both kneeling at the same time to look through the books below. It became clear that we were looking for the same thing, not mystery, not romance, but science-fiction and fantasy.

I joined the throng looking over the table; and spotted a three-volume set of Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy just as a delicate hand reached in to pick it up to look over. I already had a copy of the books, myself; the woman who’d taken them tucked them under her arm. She was directly ahead of me in the line moving left to right along the table, and this meant that as we went on we were also both kneeling at the same time to look through the books below. It became clear that we were looking for the same thing, not mystery, not romance, but science-fiction and fantasy.

So after making our way through the whole table, we fell to talking, in a side-room filled with old National Geographic magazines. Grace turned out to be clever, a writer, and also a dedicated reader (a Le Guin fan, she already had the first Earthsea book, but was missing the second and third). We talked for an hour, and then went and had lunch, and then went on to another book sale that happened to be taking place that day. And we exchanged e-mails, and met again, and so things went on, and now we look at the McGill Book Fair as marking our anniversary because it’s easier than remembering the exact day on October that we met and fell in love (but it was the 25th). The point, I suppose, being that sometimes you find mystery and romance whether you’re looking for them or not.

Back in 2010, Grace, who had got to the fair just before it opened and had first investigated the downstairs, tells me that there’s actually a separate section for science-fiction this year, and it is on this upper floor just a few tables over. She’s already found a few possible books for me, writers that she knows I like: a one-volume collection of Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Short Sun (completing my collection of his various Sun books), and a copy of Jack Vance’s Madoc (the last volume I was looking for of his Lyonesse trilogy). I finish looking over the English Lit, and join her at the sf table.

Back in 2010, Grace, who had got to the fair just before it opened and had first investigated the downstairs, tells me that there’s actually a separate section for science-fiction this year, and it is on this upper floor just a few tables over. She’s already found a few possible books for me, writers that she knows I like: a one-volume collection of Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Short Sun (completing my collection of his various Sun books), and a copy of Jack Vance’s Madoc (the last volume I was looking for of his Lyonesse trilogy). I finish looking over the English Lit, and join her at the sf table.

I find a bunch more books that I was looking for, and some I didn’t even know I needed. Having picked up a copy of Dan Simmons’ Olympos at another sale, I find the preceding book, Ilium. I find a one-volume omnibus of George Alec Effinger’s three-book Audran Sequence (I had the first two books, and hadn’t known there’d been a third published). There are some books by Tanith Lee, including some of her Tales From the Flat Earth — but I haven’t read the books in that series that I own, and can’t remember offhand which I’m looking for and which I already have. I do buy a copy of the first two of her Secret Books of Venus, along with John C. Wright’s The Golden Age, and, out of pure nostalgia, Lyndon Hardy’s Riddle of the Seven Realms.

Grace has good luck also, finding, among others, books by Donald Kingsbury, David Feintuch, Robin Hobb, and David Brin, as well as a copy of the first volume of Isaac Asimov’s autobiography, In Memory Yet Green. “I almost got volume 2 as well,” she says, “but someone snatched it up while I was considering it, the dirty rat. Always do your considering with the book firmly in hand.”

Grace has good luck also, finding, among others, books by Donald Kingsbury, David Feintuch, Robin Hobb, and David Brin, as well as a copy of the first volume of Isaac Asimov’s autobiography, In Memory Yet Green. “I almost got volume 2 as well,” she says, “but someone snatched it up while I was considering it, the dirty rat. Always do your considering with the book firmly in hand.”

It’s a good tip. One of several things worth bearing in mind if you go to a big book sale. Other examples: you can expect to be pushed and bumped into, as most sales take place in rooms just a bit too small for the number of people and books within them; of course it’s obviously wrong to initiate the shoving deliberately, however tempting it may be. It’s acceptable to duck down to investigate boxes under the table, but good form to try to stay out of people’s way while you’re doing it. It’s often a good idea to come to a sale with heavy bags or boxes of your own, but a bad idea to wear a bulky backpack which clogs the aisles. And, if in doubt about whether a box of books is for sale or has been gathered by somebody nearby, it doesn’t hurt to ask.

There have been issues with hoarding at the McGill sale in the past. Last year the sale initiated a rule that you can’t have more than one box of books going at once; no filling a box, setting it aside, and going back for more. Which didn’t stop Grace (and me) from being annoyed at missing most of the sf at last year’s sale, when some guys came along to the box holding most of the fair’s science-fiction books and just bought the whole thing.

I’ve heard of people, some of them at local sales, who hit the tables with a bar-code reader and handheld internet device. They can scan any book with a bar code, and find out what it’s going for on the internet, at Amazon or AbeBooks or wherever they like (you can find a defensive article about this sort of thing here). Most bibliomaniacs see something distasteful in this practice; unlike actual dealers, who have hard-earned expertise in their fields and who actually care about books, these buyers are drones. You might as well send a robot around to buy books. What’s the point?

To me there’s a real joy in book sales. There’s the feeling of looking for hidden treasure; very personal treasure, books that mean something to you, that you recognize as important, and which you can pluck out of the mass of the sale to preserve on your own shelves. There’s a joy to a good book sale, an unpredictability. You have no idea what you’ll find; a book you never heard of by a favorite writer, a book that completes a collection, a book you’ve heard of but never expected to find. It is, as was literalised for me four years ago, the experience of finding an unexpected grace.

But this year’s sale, science-fiction aside, is a bit duller than I’d like. I find a few more nice books here and there; I pluck a hardcover by Harold Lamb, Theodora and the Emperor, from the history table. The dust jacket’s more-or-less intact; that can affect the value of a book, sometimes by as much as a factor of ten. But I don’t buy books to resell them. Value is an interesting side-note, but not overall significant. I’m a reader. I don’t buy first editions of books I already own, either (well, okay, so I buy a copy of John Cowper Powys’ Maiden Castle, but that’s Powys, who’s an all-time favorite. I don’t think I’ve ever bought an edition just for the sake of having an edition before. Well, okay, once, but that Gnome Press Conan the Conqueror was just sitting there in the flea market. I mean, come on.)

But this year’s sale, science-fiction aside, is a bit duller than I’d like. I find a few more nice books here and there; I pluck a hardcover by Harold Lamb, Theodora and the Emperor, from the history table. The dust jacket’s more-or-less intact; that can affect the value of a book, sometimes by as much as a factor of ten. But I don’t buy books to resell them. Value is an interesting side-note, but not overall significant. I’m a reader. I don’t buy first editions of books I already own, either (well, okay, so I buy a copy of John Cowper Powys’ Maiden Castle, but that’s Powys, who’s an all-time favorite. I don’t think I’ve ever bought an edition just for the sake of having an edition before. Well, okay, once, but that Gnome Press Conan the Conqueror was just sitting there in the flea market. I mean, come on.)

Downstairs Grace and I find more books for my new niece. Narnia; The Dark is Rising; about a dozen Oz books. It`s been a good fair for her, and she’s only four months old. I add a rhyming dictionary for myself, which is something I’ve been wanting (and at two dollars, the price is right), and that’s the end of the sale for another year.

—Or not quite. The next day I have some business at the McGill library. Why not, I think, pass by the book fair again? At a sale that size, with boxes upon boxes under the table, you can often miss things the first time around.

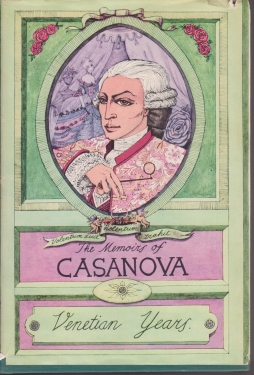

So I go back in to the high-ceilinged upper room. The crowds are gone; so are most of the books. A few McGill students are here and there in the empty aisles, chatting to each other, exclaiming that they had no idea this sort of thing existed, and wondering if it happens every year. I pass by one of the volunteers, who’s sorting out a six-volume edition of Casanova’s memoirs. It’s an attractive set, hardcover, from about 1930, all the books in mostly-intact dust jackets. But the cost, $25, although very reasonable, is more than I particularly want to part with.

So I go back in to the high-ceilinged upper room. The crowds are gone; so are most of the books. A few McGill students are here and there in the empty aisles, chatting to each other, exclaiming that they had no idea this sort of thing existed, and wondering if it happens every year. I pass by one of the volunteers, who’s sorting out a six-volume edition of Casanova’s memoirs. It’s an attractive set, hardcover, from about 1930, all the books in mostly-intact dust jackets. But the cost, $25, although very reasonable, is more than I particularly want to part with.

I go on. I find a collection of Leigh Hunt’s short stories, which is very nice. An edition of Robert Herrick’s poetry, which I’ve had a soft spot for ever since studying it in a class about fifteen years ago. Not bad, considering how thoughly-picked-over the tables are.

I find myself thinking again about those Casanova memoirs. I’ve always vaguely wanted a set. But they’re old enough, I reason, that they’re probably censored or expurgated. Probably. I decide to double-check. It turns out that not only are they complete, but that they’ve been translated by Arthur Machen, author of The Great God Pan.

That settles things. I dither over it for a few minutes, but I can’t turn away now. I get a box, and add the Casanova, along with the Herrick and Leigh Hunt. Then, just to top it off, I check the sf section again. The Tanith Lee books are still there; and last night I’d happened to check which of the Flat Earth books I had and which I didn’t. The ones that I didn’t I add to the box, and that’s it for me.

It’s a decent year. Thirty-odd books, not counting the ones for my niece; a couple less than last year. A total cost of about ninety dollars. The sale’s getting more expensive, but what isn’t these days? There’s life in the McGill book fair yet.

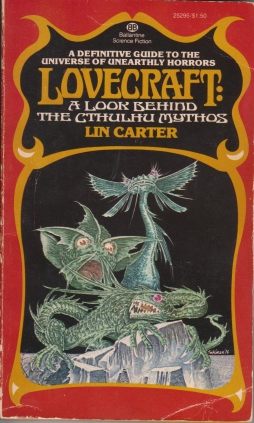

Besides, earlier in the month I went to the annual used book sale at Concordia University. Many more books there this year than in the past, and many of the ones I bought cost only a dollar or two—a bunch of history books, Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, a couple more Tanith Lee novels … and then there’s also the Westmount Library sales, where I picked up a copy of Hal Duncan’s Vellum last year … and those sales in Verdun where I found Pamela Dean’s Tam Lin and Lin Carter’s book on Lovecraft … and, and, and.

Besides, earlier in the month I went to the annual used book sale at Concordia University. Many more books there this year than in the past, and many of the ones I bought cost only a dollar or two—a bunch of history books, Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, a couple more Tanith Lee novels … and then there’s also the Westmount Library sales, where I picked up a copy of Hal Duncan’s Vellum last year … and those sales in Verdun where I found Pamela Dean’s Tam Lin and Lin Carter’s book on Lovecraft … and, and, and.

And always there is another sale. Always another unexpected wonder, just waiting, among yesterday’s best-sellers, among the tattered cardboard boxes, among the dust and pipe-smoke, among the nice if perplexed elderly ladies running the show. The bargains, the treasure, the joy and the grace, the romance and the mystery, are still out there. One way or another, I expect they always will be.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

Does the Casanova give the artist for the jacket illustration? Because it looks a little like Rex Whistler.

Unfortunately, there’s no information about the artist who did the jacket illustration. The other five jackets are all in a similar style, but there doesn’t seem to be a signature anywhere (nor any info inside the books).