Top Choice October: Dracula ‘58 (Horror of Dracula)

October films come in two flavors for me: Universal and Hammer. I have affection for almost any Gothic horror films these studios produced during their Golden Ages (1930s and ‘40s for Universal, 1950s and ‘60s for Hammer), even the lesser entries. The studios have such opposite visual approaches to similar material — the black-and-white shadows of Universal, the rococo lurid colors of Hammer — that they create a perfect Yin and Yang for Halloween, a Ghastly Story for Whatever Suits Your October Mood.

October films come in two flavors for me: Universal and Hammer. I have affection for almost any Gothic horror films these studios produced during their Golden Ages (1930s and ‘40s for Universal, 1950s and ‘60s for Hammer), even the lesser entries. The studios have such opposite visual approaches to similar material — the black-and-white shadows of Universal, the rococo lurid colors of Hammer — that they create a perfect Yin and Yang for Halloween, a Ghastly Story for Whatever Suits Your October Mood.

And what suits my mood best, most of the time? Hammer’s 1958 Dracula, released in the U.S. as Horror of Dracula. This isn’t my top pick of the Hammer canon — I lean toward two 1968 films for that honor, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed and The Devil Rides Out — but it is the film I turn to more than any other when the calendar changes into the deep orange and serge hues of the Greatest Month.

Dracula ‘58 is my favorite version of the Dracula story, and perhaps my favorite vampire anything — with the possible exception of Matheson’s novel I Am Legend. It has flaws, but scoffs at me for even thinking that they exist. It is so desperately alive, so exploding with its own entertainment value, and so rich in execution that it never fails to be “exactly what I wanted to watch tonight.” I can say that about few films, even objectively better films.

Dracula is the cornerstone of the Hammer Film Productions legend, and an icon of the Anglo-Horror revival that seized the 1960s. Hammer had already entered the field of horror with their science-fiction “Quatermass” films, the intriguing spiritual spin-off X the Unknown, and the unusual creature-search adventure The Abominable Snowman. In 1957, the studio made their first color period horror movie, The Curse of Frankenstein, which whirled far away from both standard source materials — Mary Shelley’s novel and the 1931 James Whale film starring Boris Karloff — to represent an accidental manifesto of the new terror. It also introduced the horror-watching world to the double-team of Peter Cushing (Doctor) and Christopher Lee (Monster).

But The Curse of Frankenstein is a very good film, while the follow-up of Dracula is a superb one. As Hammer prepared to film a sequel to their Frankenstein success, The Revenge of Frankenstein, they also set in motion the filming of the other famous Gothic movie monster from Universal’s stable. The filmmakers involved in The Curse of Frankenstein all moved over to the new film: director Terence Fisher, screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, producer Anthony Hinds, production designer Bernard Robinson, composer James Bernard, cinematographer Jack Asher, editor James Needs, and stars Peter Cushing (Doctor) and Christopher Lee (Monster). The result was a fresh synthesis that sealed the style that Hammer would use through the next decade.

Dracula had a tricky time getting funding. Universal-International originally was cold to the production (the studio was outwardly hostile toward The Curse of Frankenstein and made it clear they would pursue legal action if the film’s monster resembled the famous Jack Pierce make-up design of their Frankenstein Monster), but finally chipped in for the international rights. The rest of the money came from the National Film Finance Council. The massive success of Dracula would change Universal’s mind about Hammer doing versions of movie monster they had made famous, and with next year’s The Mummy, Universal-International entered an agreement with Hammer to give them full access to their catalog. The Mummy then went on to make even more money than Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula.

Dracula had a tricky time getting funding. Universal-International originally was cold to the production (the studio was outwardly hostile toward The Curse of Frankenstein and made it clear they would pursue legal action if the film’s monster resembled the famous Jack Pierce make-up design of their Frankenstein Monster), but finally chipped in for the international rights. The rest of the money came from the National Film Finance Council. The massive success of Dracula would change Universal’s mind about Hammer doing versions of movie monster they had made famous, and with next year’s The Mummy, Universal-International entered an agreement with Hammer to give them full access to their catalog. The Mummy then went on to make even more money than Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula.

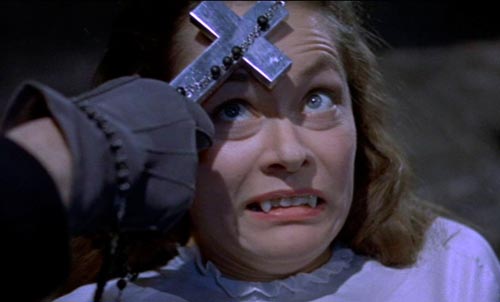

With the distance of over half a century, it is difficult for modern audiences to understand how shocking and powerful Hammer’s Dracula was when it reached theaters. The Vampire King is incredibly physical and violent, leaping over tables, bestially snarling, hurling people across rooms, drooling fire-engine-red blood from his fangs. His adversaries don’t hold back, either: the camera doesn’t flinch from showing stakes driven into chest, squirting blood, while an enthusiastic Van Helsing wields the hammer. Much of this comes from director Terence Fisher, who always kept his films keyed on movement and grand theatricality. Fisher delivered action-oriented finales, and the closing moments of Dracula ‘58 were filled with so much energy and agony that audiences were stunned. I still think the ending of Dracula is one the best horror-finales ever lensed: Dracula is not destroyed, he is violently and harshly annihilated after a thundering fight and chase build-up.

Looking at Dracula ‘58 in the history of adaptations of Bram Stoker’s novel presents a weird confluence of elements and new ideas. A combination of budgetary concerns and the desire to do something different made interesting changes to Stoker’s novel and popular conceptions from the Bela Lugosi film of 1931. There are superficial differences, such as Dracula’s inability to change into animal form (“That’s a common fallacy,” Van Helsing announces, thus saving about £5,000 in one sentence) but many that make significant changes in the whole subtext of the story.

First, Dracula (Christopher Lee) is no longer the initial aggressor or the active mover of the story. It’s Van Helsing (Peter Cushing) who puts events into motion and makes the first move against the Count. Bram Stoker’s Count planned to invade England with an army of coffins and called Jonathan Harker to his castle to make the arrangements. But in Jimmy Sangster’s script, Dracula is quite willing to remain in his fortress with his vampire bride (Valerie Gaunt) and feed off the local population, and let the rest of the world mind its own business. But Van Helsing sends Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) to the castle to destroy Dracula on the excuse that he will catalog the Count’s library. When Harker (an idiot, as always) screws up the assignment and only manages to kill Dracula’s bride before Dracula kills him, the Count decides to get his revenge—and a new bride—and seeks out Jonathan’s fiancée Lucy (Carol Marsh) and then Lucy sister-in-law Mina (Melissa Stribbling). Although never stated, I think that Dracula is also hunting to find someone to really actually his library. Somebody who won’t kill his live-in girlfriend. Freelancer librarians these days, I tell you.

Second, Dracula appears to be monogamous. Only one vampire bride lives in his castle. Budget, I’m assuming, but it also accents Dracula’s anger at Van Helsing and Co. for coming along and interfering with his life. Hammer films are known for their relatively brazen sexuality, and Dracula has a quite a few heaving bosoms waiting in anticipation of Dracula’s embrace (just watch the way young Lucy lays herself out like a girl on her wedding night, awaiting her handsome groom), but it is interesting that the Vampire King here only focuses on one victim at a time, and moves on to the next whenever his opponents kill the current one.

Second, Dracula appears to be monogamous. Only one vampire bride lives in his castle. Budget, I’m assuming, but it also accents Dracula’s anger at Van Helsing and Co. for coming along and interfering with his life. Hammer films are known for their relatively brazen sexuality, and Dracula has a quite a few heaving bosoms waiting in anticipation of Dracula’s embrace (just watch the way young Lucy lays herself out like a girl on her wedding night, awaiting her handsome groom), but it is interesting that the Vampire King here only focuses on one victim at a time, and moves on to the next whenever his opponents kill the current one.

Third, Dracula is no longer a foreign menace, but a domestic one. The budget curtailed the cross-continental action of the novel. The story instead occurs entirely in a fictionalized German country (a.k.a. “Hammerland”) where Van Helsing has established headquarters in Carlstadt, a remarkably Anglo city that is only a carriage-ride away from Dracula’s haunt in Klausenberg (the German name for Cluj, a Romanian city, but since this is a fantasy-geography there’s no reason to believe that it really is Cluj, and it seems far too small).

Fourth, and perhaps most important, is the significant changes that Sangster’s script makes to the character of Van Helsing. (Dracula’s motivations are different from the character in the novel, but he still seems closer to the vicious tyrant of the book than the figure pioneered on stage and then in the 1931 movie.) Stoker’s Van Helsing is an archetype of the Wise Mentor figure, a Merlin giving advice to the young knights of the Round Table in their quest to slay the dragon. Sangster re-writes Van Helsing as a younger man, the active hero of the story who has hardly any companions at all except the reluctant Arthur Holmwood (Michael Gough, later of Alfred the Butler fame), who is about the same age as Van Helsing. Van Helsing doesn’t stumble upon Dracula’s existence and take up of eliminating him as in the book; his whole life is focused on the eradication of the plague of the undead, with Dracula as his primary target. The changes to Van Helsing’s character are even more pronounced in Peter Cushing’s performance, which I will discuss in more detail later.

After Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee is the actor most associated with the Vampire King, and his performance benefits from having nothing to do with the evening clothing-attired version that Lugosi made famous. Lee’s Count Dracula is dressed in simple, all-consuming black, with a cape hiding him from head to foot. He exudes the manners of a cruel tyrant of the Middle Ages, no longer polite or filled with social grace, but brimming with the steel arrogance that he simply must be obeyed.

After Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee is the actor most associated with the Vampire King, and his performance benefits from having nothing to do with the evening clothing-attired version that Lugosi made famous. Lee’s Count Dracula is dressed in simple, all-consuming black, with a cape hiding him from head to foot. He exudes the manners of a cruel tyrant of the Middle Ages, no longer polite or filled with social grace, but brimming with the steel arrogance that he simply must be obeyed.

The Christopher Lee Count Dracula is foremost a physical creature. Lee has often said that he sought to make Dracula “more human,” and I do not think he means “sympathetic.” Even though Dracula is on a quest to get revenge for his bride’s staking, he’s hardly a figure of pathos. He didn’t love the vampire woman that Harker killed; he owned her as any deserving tyrant would own his trophy beauty, and now he wants beautiful property to replace her. What I believe Lee means about a “human” Dracula is a flesh-and-blood creature that is vitally alive, even though it is technically undead. This Dracula hurtles across the screen, running, leaping, and throttling. It must have stunned audiences in 1958 when Dracula made his sudden second appearance, after a scene of cold commonplace hospitality to Harker, as a blood-drooling red-eyed monster. It still has shock power today.

But as great and career-making a role as Dracula was for Christopher Lee, at the end of the film it Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing who leaves viewers amazed. I’ve seen Dracula ‘58 as many times as I’ve seen any of my favorite movies, and sometimes I prefer some parts of it more than others, and sometimes I find myself critical of sections that I wasn’t critical of the last time and even rejoicing in sections I was criticizing the time before. I think this is true of any movie that we love with rough honesty, something different than childhood idolization. (Although childhood idolization is itself wonderful; joy should never be denied.) However, what always is and will always be a pure joy in Dracula ‘58 for me is Peter Cushing as the finest and most marvelous embodiment of a vampire hunter.

Peter Cushing is One of My Favorite People. Seeing him in anything, his face, his expressions, his voice tones, his command of all around him, is a wonder. I can never have enough of Peter Cushing, even when he’s doing lesser work (yes, he was capable of it, although it seems impossible when I write it down). That he is dead and there is a terminal point to his work is a painful thought, but no one lives forever. Not even Dracula, and that’s because Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing is there to put an end to him.

Dracula ‘58 is really Van Helsing — much more so than a certain horrible film of the same name, which is nominally about a Dr. Van Helsing. In Terence Fisher’s film, it is Van Helsing’s world, and Dracula is only (un)living in it … and on borrowed time. If Dracula could see with clear eyes the man he is up against, he would crawl back to his castle, bolt all the doors, and lie in his coffin until he starved to death from blood deprivation. Because there is no way this semi-mad, fully brilliant, thoroughly ambitious Dr. Van Helsing can ever be beaten. He is a straddling colossus between science and the supernatural, but dismissive of the conventional thinking on both, and driven with a puritanical haughtiness that is ultimately not puritanical at all, but bloodthirsty. He’s almost a villain in his ruthlessness, and if he were not on our side opposing the evil undead, I’m sure he would have enslaved every single one of us already and killed all the heroes trying to stop him.

Dracula ‘58 is really Van Helsing — much more so than a certain horrible film of the same name, which is nominally about a Dr. Van Helsing. In Terence Fisher’s film, it is Van Helsing’s world, and Dracula is only (un)living in it … and on borrowed time. If Dracula could see with clear eyes the man he is up against, he would crawl back to his castle, bolt all the doors, and lie in his coffin until he starved to death from blood deprivation. Because there is no way this semi-mad, fully brilliant, thoroughly ambitious Dr. Van Helsing can ever be beaten. He is a straddling colossus between science and the supernatural, but dismissive of the conventional thinking on both, and driven with a puritanical haughtiness that is ultimately not puritanical at all, but bloodthirsty. He’s almost a villain in his ruthlessness, and if he were not on our side opposing the evil undead, I’m sure he would have enslaved every single one of us already and killed all the heroes trying to stop him.

The above paragraph is my way of describing Peter Cushing’s performance in Dracula. I find myself lost trying to write about it in standard film review language. Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing is one of the great layered film characters. He’s heroic, but also unable to relate to other people in a socially normal way. His lack of empathy, often demonstrated in his matter-of-fact dealing with the confused Arthur Holmwood, borders on psychopathic. Van Helsing knows he is right and that he is all that stands between humanity and the plague of the undead contagion, and he does not understand why other people even need to have this explained to them. Or why somebody might object to having his sister’s corpse gorily staked in her coffin. The exception that proves the rule is that Van Helsing’s only kind exchange with anybody in the film is with an eight-year-old girl (Janina Faye). He appears to feel some guilt over sending Jonathan Harker off to his death at Castle Dracula, but it seems this is more Van Helsing’s self-reprobation for his own logistical failing, not that Jonathan Harker was a close friend. He can hardly offer anything in the way of comfort to Jonathan’s fiancée Lucy or Lucy’s family aside from insisting they have to let him have his way with the stake and the cross and the garlic or they will all regret it.

Although an inexpensive film, Dracula ‘58 disguises the budget with the tremendous work of artistic director Bernard Robinson, the man who became the visual architect of the Hammer House of Horrors. Robinson’s work is so different from the style of the Universal films that he was almost fired for what he was attempting. At first glance, Dracula (and most Hammer movies of the age) are alarmingly bright, with few shadows and remarkably clean Gothic interiors. However, Robinson’s genius lay in his choice of décor and his use of color to create a sumptuous fantasy world. The terror of a Hammer Film’s sets are not in darkness or webs, but in texture, decadence, and detail. The smallest object placement can create weird, upsetting compositions, or add a sense of reality to the inherently unreal Victorian world. For example, the large stove made of green porcelain in Van Helsing’s study in the background and the “magical machine” of a Dictaphone in the foreground. Dracula’s castle has a visual marvel on its floor, a marble zodiac wheel inscribed with Homeric Greek along the edge. Harker’s room in the castle is crammed with bric-a-brac, including a writing desk with astonishing woodworking detail on the drawers. And Dracula’s vaulted tomb is a place filled with the heaviness of stone and earth, a foreboding place even though it has few ornaments.

James Bernard’s score deserves special mention for how it contributes to the new atmosphere of Gothic horror alongside Bernard Robinson’s designs. Bernard’s music thunders and stabs. It rejects subtlety for huge brass booms and neurotic strings. It’s hyper-aggressive, but it works, because the film is virile enough to move to that sort of rhythm. Bernard’s “Dracula Motif” is a wonder of simplicity, three notes synchronized to the syllables of “DRAC-u-la!” “DRAC-u-la!” (James Bernard enjoyed creating his themes to match the syllables of the titles. He did astonishing work with long titles such as The Devil Rides Out—“The … De-vil … RIDES OUT!”—Frankenstein Created Woman, and Taste the Blood of Dracula, both of which use sweet love themes, believe it or not.)

James Bernard’s score deserves special mention for how it contributes to the new atmosphere of Gothic horror alongside Bernard Robinson’s designs. Bernard’s music thunders and stabs. It rejects subtlety for huge brass booms and neurotic strings. It’s hyper-aggressive, but it works, because the film is virile enough to move to that sort of rhythm. Bernard’s “Dracula Motif” is a wonder of simplicity, three notes synchronized to the syllables of “DRAC-u-la!” “DRAC-u-la!” (James Bernard enjoyed creating his themes to match the syllables of the titles. He did astonishing work with long titles such as The Devil Rides Out—“The … De-vil … RIDES OUT!”—Frankenstein Created Woman, and Taste the Blood of Dracula, both of which use sweet love themes, believe it or not.)

Orchestrating this work is director Terence Fisher. Dracula isn’t necessarily the best work he ever did, it is perhaps the most typical of his wild and aggressive style and how it influenced all of Anglo-horror to come.

Hammer continued to make Dracula films until the late ‘70s, when the company ceased film production. The results were uneven. The first sequel, 1960’s The Brides of Dracula, does not even feature the Count, but it was a true sequel because Peter Cushing returned as the crusading Van Helsing and took on one of Dracula’s aristocratic descendants. This florid and strange movie is one of Hammer’s most beautiful, and easily the finest of the Dracula sequels. It wasn’t until 1966 that Hammer got Christopher Lee to put on the fangs again (although he refused to speak any of the dialogue written for him) and produced the attractive-looking but mostly dull Dracula: Prince of Darkness, with Van Helsing nowhere to be seen. It was also the last of the Dracula films that Fisher directed.

The series improved a little with the next outing, 1968’s Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, and then got back to near-great status two years later with the Peter Sasdy-directed Taste the Blood of Dracula, where the Count turns the children of wealthy decadents against them. But with the cheap-looking Scars of Dracula in 1971, the series entered a steep decline. Peter Cushing returned as Van Helsing’s descendant in the first movie with a modern setting, Dracula AD 1972, a film with a certain campy charm because of the swingin’ Chelsea backdrop. Too bad Dracula spends most of his time hanging around a dull ruined church while the rest of the movie has fun. The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1974) keeps the modern setting and Peter Cushing, but tries to fashion an espionage thriller from the material and ends up showing that series was blood-drained. The last film, also released in 1974, is an interesting genre-masher, The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires, which puts the Hammer movie into a Shaw Brothers’ Kung Fu feature. Cushing played the original Van Helsing, but Lee was done by this time, and Dracula’s short appearance was undertaken by John Forbes-Robertson.

Hammer Film Productions is once again releasing movies, with a film of The Lady in Black forthcoming. Will they re-visit their old standby of Count Dracula again? At this moment, the only “Dracula” film project that might possibly excite is one with the name “Hammer” on it.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Your opening paragraph says it all.

October always gravitates me back to Universal and Hammer classics. I enjoy a lot of other, newer horror movies, but there is something about the older movies’ atmospheres and styles.

Maybe it’s simply because they are what I grew up watching on Saturday afternoon’s ‘Creature Double Feature’.

I prefer Amicus, psycological horror in sketches and in modern settings is more interesting for me than the classic monsters

by the way what about less known Hammer films like The abominable snowman or The gorgon?

hey pmcnamee67, you were a lucky boy, in Spain in the 80’s fantastic films what kind of taboo on tv, saturday afternoon we had very boring westerns of the 40’s and 50’s that almost make me hate western, one of my less favourites genres…

Aw, why so little love for The Satanic Rites of Dracula? Okay, Lee’s presence as Drac is minimal and that’s an issue, no mistake.

But there’s so much to relish… Swashbuckling espionage action with the servants of Dracula wielding silenced sniper rifles. Ancient supernatural evil gone corporate in what might be the oddest confrontation between Lee and Cushing on film. A couple strikingly lurid setpieces, including one of the most memorable vampire-stakings in all of Hammer. A ripping score that slams Gothic flourishes into a Bondian spy theme with wild abandon.

And the outfits. Only in the 1970’s would the minions of the Immortal Lord of Vampires ride motorcycles and be tricked out in uniforms consisting of turtleneck sweaters and sheepskin vests. Some groovy ghoulies, indeed.

The Gorgon in one of my favorite Hammer films: I’ve reviewed it here.

And The Abominable Snowman as well.

Chris, your paragraph about Satanic Rites is a microcosm of my problem with this movie. All that . . . and it’s still torpid and boring? It has no right to be middling and dull with that sort of craziness. It’s better than Dracula AD 1972, which is so disappointing because it never lets Dracula interact with its premise, the modern world of London, and just keeps him in a Gothic church. But watching Satanic Rites just makes me shake my head and wish they could have had the energy of a different director (like Mike Hodges! can you imagine!) putting it together.

[…] weeks ago I discussed the key Hammer Horror film for Halloween, Dracula (1958). It would be a grave omission not to discuss my key Universal Horror film for Halloween—especially […]