Babble About Cabell: Domnei

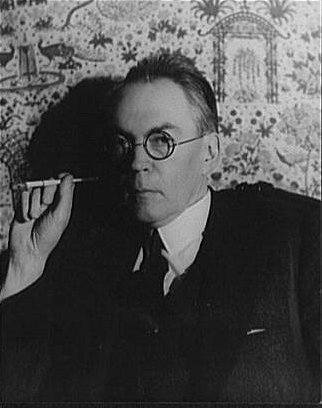

James Branch Cabell‘s often expressed ambition was to “write beautifully of perfect happenings.” He was born in 1879; one of his first jobs was reporting the society news in New York City; and his work frequently hinges on romantic love of a very old-fashioned sort. A reasonable person might conclude from all this that the man wrote slop but, as so often, the reasonable person would be wrong.

James Branch Cabell‘s often expressed ambition was to “write beautifully of perfect happenings.” He was born in 1879; one of his first jobs was reporting the society news in New York City; and his work frequently hinges on romantic love of a very old-fashioned sort. A reasonable person might conclude from all this that the man wrote slop but, as so often, the reasonable person would be wrong.

Where to start with Cabell? He didn’t go out of his way to make it easy. His major work is a 25-book

Where to start with Cabell? He didn’t go out of his way to make it easy. His major work is a 25-book eikosipentology ohmygodthatstoomanybooksology series titled The Biography of Dom Manuel. Only one of the books (Figures of Earth) actually deals with Dom Manuel, the legendary hero of a fictional French county Poictesme. The rest of the books supposedly deal with Dom Manuel’s life as it passes to his heirs, physical and otherwise, under three grand divisions: chivalry, poetry, and gallantry. If you think it is possible to be more old-fashioned than this, I’m afraid my seconds will have to call upon you for an explanation.

Not all of this stuff is equally readable, and some of it is not readable at all. Things like Beyond Life: The Dizain of the Demiurges is strictly for the Cabellian completist or the literary masochist. (There may be some overlap between those groups.)

But Cabell had complete control over his style, and he used it to hilarious and harrowing effect. He spun fantasies of heroes and damsels in a Middle Ages that never was but (in the words of one of Dashiell Hammett’s most cynical characters), “Cabell is a romantic in the same way the horse was Trojan.” He tells these tales, unrolls these dreams; he cherishes them; he deconstructs them; he mocks them–somehow all at the same time. Cabell’s spirit kills these dreams; his letters give them life.

People often want to begin at the beginning, but there is no beginning and no end with Cabell. His biggest hit (due to the obscenity charges brought against it) was Jurgen. That’s still worth reading, by all means.

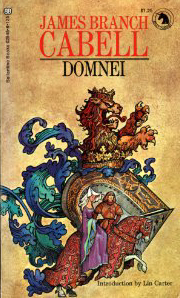

But I’ve long thought Cabell’s most accessible book is one of the earlier ones, Domnei. It’s on Google books, both in its revised 1921 version and in its original sappier avatar as The Soul of Melicent. (The title was forced on Cabell by his publishers and he changed it back when he had more clout.) But, if you can find it, I recommend reading the book in the Storisende edition or one of its reprints (like the one that appeared in Lin Carter’s legendary Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in the 70s). Those versions have two advantages over all others. They have Cabell’s drily hilarious Author’s Note, and also another episode of the Biography The Music Behind the Moon.

Domnei pretends to be a translation from a fragmentary French romance, telling the tale of Perion de la Forêt (an outlaw accused of treachery and murder) and Melicent (the oldest of Dom Manuel’s daughters). Their love is hopeless unless he can cleanse his name and earn a reputation and a fortune in the wars against “heathenry.” (Not Islam: remember this is an imaginary Middle Ages. Perion’s major antagonist is a Greco-Roman polytheist. This makes no sense at all, but it does give Cabell a chance to make an egregious display of his classical learning. That sort of thing disgusts me deeply, but de gustibus non disputandum, eh?)

But Perion is betrayed by a friend and captured by the Proconsul Demetrios. Melicent goes in disguise to Demetrios’ court to bargain for her lover’s release. Demetrios insists that Melicent herself is the only ransom he will accept for the hero’s life. Melicent cuts the deal and Perion, once he is free, is given a letter detailing the terms of his release. The rest of the story concerns the struggles of these star-crossed lovers to overcome all obstacles and fulfill their youthful promises of love.

Let me ruin the book for you right now. They will overcome all obstacles and fulfill their youthful promises of love. Cabell is a Romantic, right? Like the horse was Trojan. No obstacle can stand in the way of true love. Except success. When Perion, not the brightest man in the world, comes face to face with this middle-aged woman he hasn’t seen in decades and knew only briefly in his youth, will he still be interested in her? Will she have any interest in him? Why? These are the anti-Romantic questions Cabell is prepared to ask and, in a way, answer. But the answers are never final, so Cabell tends to ask them again in different books.

I’m not sure Cabell’s answers, or even his questions, have so very much import anymore, but I love these books for the sureness of their execution. At one point in Domnei, the hero Perion has been thrown into prison and is going to be executed. The villain Demetrios can’t have anyone else killing his favorite antagonist. So he disguises himself as a minstrel and sneaks into the prison, tricking the jailor into taking him to Perion’s cell. Then this romantic, sentimental event occurs.

Demetrios, who was not tall, lifted the gaoler as high as possible, lest the beating of armoured feet upon the slabs disturb any of the other keepers, and Demetrios strangled his dupe painstakingly. The keys, as Demetrios reflected, were luckily attached to the belt of this writhing thing, and in consequence had not jangled on the floor. It was an inaudible affair and consumed in all some ten minutes. Then with the sword of Bracciolini Demetrios cut Bracciolini’s throat. In such matters Demetrios was thorough.

In his best books, whatever else he has on his mind (or wants to put in yours), Cabell never forgets to provide a story, well-stocked with monsters and miracles and magic and heroes and villains. In such matters, Cabell is thorough.

Why am I telling you all this?

I think it started like this. I was raving and waving my hands and things at Dragon*Con, talking about Cabell. And John O’Neill, in an effort to talk me off the ledge, suggested I write something about JBC for the Blog Gate. The project blossomed, post-con, due to the influence of Claire Cooney, who makes most things blossom. (It’s science. Consult a blossomologist or, even better, clairographer for the details.) Now it looks like this will be an irregular two-headed series of pieces on Cabell. Claire’s going to review some of the books (including Figures of Earth and The High Place) and I’m going to look at a few of the others, starting with a piece on Domnei. Which, as you have already concluded, was what this was. So now I’ll conclude too.

This is just exactly right.

And now I must needs read Domnei, although I just told someone that I feel I needn’t read another Cabell for at least another year, having finished Figures of Earth, grateful I came out of it with my soul intact and my eyes uncrossed.

Which is not to say I didn’t enjoy it.

Still, outlaws?

I’m so totally there.

This is a great post, and a great idea for a series! I like Cabell’s work a lot, in its bitter way, and I’m eager to see what you have to say about it. For me, he mixes so much folkloric and fantastic material with a kind of disillusioned-but-mournful-about-it stance, and writes with such brevity and wit, that there’s almost a dissonance in reading it; it’s as if the books ought to be lushly-written adventures, or ought to be terse, cynical satires, but somehow fuse the two things to become … well, both and neither and something else again.

Looking forward to more!

Coincidentally, there is a Cabell discussion group called “The Rabble Discuss Cabell” over on the LibraryThing book-cataloguing site…