A Look at The Night Life of the Gods (1931)

THE NIGHT LIFE OF THE GODS

by Thorne Smith

Published by Dodo Press, Copyright 1931

Reviewed by Mark Rigney

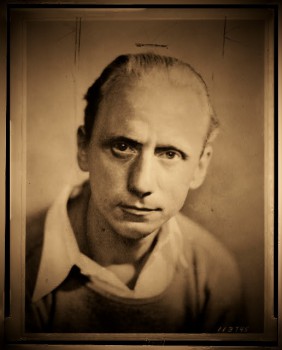

In searching for the earliest inspirations for sword and sorcery, one perfectly reasonable starting point would be Ancient Greece. The Grecian stories, after all, have survived in marked detail, and the adventures themselves are epic in scope, bloody to a fault, and literally crawling with terrifying beasties. Adapting those tales has been the work of many a writer, including (James) Thorne Smith, a massively successful fantasist now largely forgotten, who posed himself the question, “What if someone could turn the various Olympian statues in the Big Apple’s museums into flesh and blood?” Smith’s answer was The Night Life Of the Gods (1931), a cheerful Shaggy Dog of the New York variety, and a fine example of a book that no modern publishing house would touch with a thirty-nine-and-a-half-foot pole.

If Thorne Smith’s name is sounding suspiciously familiar, perhaps it should, as he is the earnest scribbler behind Topper (1926), the very same Topper in which Cary Grant later starred (as a ghost), and which eventually became a staple of early television, featuring Leo G. Carroll and sponsored by Jell-O. (Night Life Of the Gods also found its way to the silver screen; the 1935 production, starring Alan Mowbray, is said to be (deservedly) buried in a vault at UCLA.) As a book, Night Life, like virtually all of Smith’s fantastical, debauched novels, was wildly popular. That it has not remained so is perhaps a testament to the complete inability of post-modern Homo sapiens to imbibe anywhere close to the quantity of alcohol consumed by Smith’s louche, soused-to-the-gills characters.

Let me put it more bluntly: a truly astounding amount of liquor gets dispatched in the course of this book. Given that the action takes place smack in the midst of Prohibition, an era when American breweries were busily hawking malt syrup just to say alive, the book’s blood alcohol content becomes all the more astounding.

__________________

Indeed, the dedicated downing of alcohol in Night Life is not incidental, but is instead a formal and organic part of the whole, from story to style and back again, in large part because of Smith’s own tendency to tipple with, shall we say, vigor. His legend was sufficient to attract the attention of James Thurber, who included him in his memoir, The Years With Ross, in which Smith manages to disappear, inexplicably, for an entire week.

Plot-wise, Night Life Of the Gods concerns one Hunter Hawk, a disreputable but brilliant scientist who develops a clever little ray capable of turning living flesh into stone. As if this weren’t bad enough, Hawk has a between-the-sheets run-in with Meg, a curvaceous and happily pickled leprechaun who can turn statues into flesh just by wiggling her dead sexy fingers. Predictably enough, hi-jinks ensue. At the top of the statuary chain await the Olympians, and once freed from their stony encasements, the hi-jinks ensue at an ever-greater rate.

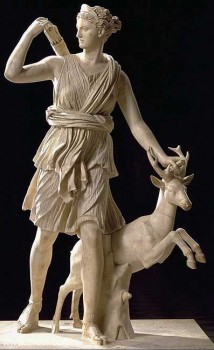

Night Life Of the Gods unquestionably belongs in the canon of 20th century fantastic fiction (H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard were contemporaries of Thorne Smith), but in character and temperament, its closer kissing cousin is Hollywood — specifically Tinseltown’s beloved screwball comedies, a genre in which breakneck pace and the witty banter of the endlessly idle rich drove masterpieces like Holiday, It Happened One Night, and Bringing Up Baby. With Night Life, the banter is almost all that holds the book’s first 150 pages together, since Smith unfolds his tale as a series of antic but disconnected incidents, most of which do nothing to advance the story or raise the stakes. Finally, Hawk and Meg visit New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and first Mercury and then Bacchus are freed from their places. In short order, and in a total hodgepodge of Greek and Roman families, Hawk and Meg revivify Neptune, Apollo, Diana, Venus (de Milo), Perseus (complete with Medusa’s severed head), and Hebe, cup-bearer to the Gods. Smith’s sometimes purple prose becomes downright efficient, as fetching Hebe announces to the world with forthright simplicity that she wants a cup to bear, while Diana . . .

…sprang noiselessly to the floor and looked coolly about her. ‘I’d like to take a pot shot at a deer,’ she announced, inspecting her bow, ‘if any of you happen to know where one is knocking about. If I had my hounds along I’d rustle up a deer for myself.’

Smith makes no attempt at all to shift the diction level of his Olympian playthings, and they speak in the exact vernacular of, say, Carole Lombard in Twentieth Century. And with everyone happily spouting the exact same (now-deceased) brand of English, the bedroom barbs and tipsy witticisms fly faster than Diana’s expert arrows. It’s actually amazing Smith got away with this stuff; this was the era of the Breen Code, after all, and while the Breen restrictions never applied to books, they encapsulated the era’s prudish, post-Victorian morality. (That is to say, its official morality.) Thus no one in Night Life ever “talks dirty” by the modern standards of internet porn, but double entendres positively litter the page. Vice, it seems, is perpetually funny, so long as it’s never déclassé.

In Thorne Smith’s world, extra-marital affairs are the norm (and only a truly bad sport would complain), and the poor do not exist––with the exception of impoverished leprechauns, but these hardly count, as the chief sign of their impecunious state is a reliance on home-made apple jack instead of fine wine or strong whiskey. That the poor should be ignored was indeed a screwball and Depression-era trope; heroes and heroines were typically wealthy to the point of redundancy (witness Katherine Hepburn in Holiday, desperate for some new entertainment––Cary Grant, for example, again––and ready to turn cartwheels in the meantime, anything for a little droll diversion). Absenting the poor was both a sign of knowing one’s audience and denying full force the wider world, and Smith, whose inebriated brand of comedy required obscene amounts of ready spending money, had no interest in challenging that convention.

Night Life does contain a few societal broadsides, mostly aimed at stodgy people with no sense of fun, but it also takes aim at the art world. Despite choosing to resurrect the Greeks (and Romans), Smith evidently thought poorly of that entire family of statuary, writing that they bored most onlookers because “…they’re complete and detailed reproductions of men and women. Our imagination doesn’t have to supply a thing. Even the fig leaves fail to suggest.” He approved of Rodin, however, and describes him as “a clever devil…because he didn’t give everything away. Always held a little back––suggested something beyond the mere medium in which he worked.”

Not that critical commentary is the central meat of Night Life Of the Gods. In fact, it’s tempting to view Smith’s work as offering a premature but lively contribution to the sexual revolution, since in his writings, nice girls do, and then they continue to do whenever possible, with evident giggling glee. Venus can hardly keep her raiment on her body, Diana steps out of her clothes upon entering any indoor space (“It’s too nice to wear about the house”), and the only thing that rescues Meg from being a tramp entire is her insistence on monogamy. Or, more accurately, the lady leprechaun professes what has come to be called serial monogamy. An accomplished and light-fingered thief, Meg (surely speaking for Smith) suggests that “…almost any man, if he stays in bed long enough and enjoys sufficient privacy will find some woman alongside of him sooner or later.” When Meg mentions dreamily that she liked having Hawk’s arms around her, Hawk replies, “On with that dress, and be ready to yank it off at a moment’s notice.”

In a curiously chaste nod to propriety, Smith does allow one female to avoid spending all her time on sex (or the pursuit thereof), and that is Professor Hawk’s twenty-something niece, Daphne. Daphne is not, however, a shrinking violet; far from it. She has earned her status as her uncle’s family favorite by being ever-ready with a drink, and game for pretty much anything her uncle’s new powers can deploy. She remains “unruined” only because she’s fallen for a dimwitted socialite who wouldn’t dare touch her before marriage (although Daphne frequently demands that he do so). Lest Daphne be viewed as a stick-in-the-mud, Smith hands her a nickname, Daffy, which she wears with pride. Indeed, all women of substance herein bear a nickname, often male; it seems that inappropriately moral women may be quickly identified by the simple lack of a nickname. Female Olympians are, of course, exempt. What superlative can one possibly rain on Venus? “Voluptuous”? “Divine”? “Cutie-Pie”?

In Smith’s version of New York City, all cops are Irish and exist to be dumbfounded, assaulted by Neptune’s mighty trident, and/or turned to stone, while blacks are waiters who say “Ah” for “I” and “de” for “the,” but do not, thankfully, fall otherwise under the baleful nib of Smith’s pen. In fact, the black characters are not criticized in the least, a pleasant surprise given the period and Smith’s otherwise regular tendency to lambaste all in sight. Indeed, even as they speak in overdone dialect, what the black characters say is pretty sensible, centering on the very sober idea that it might be wise to get out of the animated Olympians’ way.

Unfortunately, after giving the gods their freedom, Smith settles for their being nothing more than exceptionally handsome, peevish mortals. Yes, Diana is a dead shot with a bow, and Neptune can hold his breath in a Turkish Bath long enough for the attendants to be amazed, but at no point do these immortals threaten to break loose with Olympian fury and do some real damage. Even the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man knew how to do that.

What, then, do the great Greeks do? They hole up in a swank hotel and drink like there’s no tomorrow. They shop. They dine. They manage to be the dreadful bores that Hawk so totally disdains. An innocent bovine serves to illustrate the point. Smith has Meg and Mercury bring a cow up to their encampment of a hotel suite, then writes:

The news of the milking of the cow spread rapidly through the apartment, and the Olympians, forgetting their various grievances and quarrels, dropped everything and hastened to the spot. They seemed to be the sort of people who hate to miss anything, even when they find no enjoyment in whatever it is.

Later, via Hawk, Smith muses that “If a cow drank milk, it would be something like discovering perpetual motion.”

Given the clear hindsight of history, it’s a pity Smith didn’t deploy a dodo instead of a cow. Dodos––large, flightless, and unquestionably extinct––provide an ironic counterpoint to the eponymous press’s mission of resurrecting titles that would otherwise be consigned to history’s landfill, and Dodo is presently doing so at the rate of one hundred “new” titles per week. These re-released paperbacks appear in a bi-colored cover with a central illustration, the overall effect of which (especially combined with the encircled Dodo icon) is to recall almost exactly a classic Penguin pocket edition from, say, 1976. As a no-frills operation, Dodo does not spend its money on copy editors. The pages of Dodo’s Night Life have the look of a blog, where nothing is indented and enormous fields of white space march between each successive paragraph. Numerous punctuation marks are missing, especially quotations––and this is a pity, since Smith, like Roddy Doyle, writes most comfortably in dialogue, much of it either venomous or hilarious, and sometimes both.

Given the heavy reliance on dialogue, it should come as no surprise that character development is simply beside the point. So, too, given the near aimlessness of the proceedings, is plot resolution. With nearly all 21st century fictions revolving around the idea of taking damaged characters and bringing them, if not to a useful epiphany, then at least to some new phase in life, it is downright startling to encounter a work where no such considerations ever existed––where hi-jinks themselves are the only horse in the race.

Surely the Thorne Smith cocktail will not be to every reader’s taste, but for those who enjoy a historical peek into the Years That Were, or who are just plain tired of Serious Fictions and Weighty Matters, Night Life Of the Gods is the nectar you’ve been waiting for––and Hebe will be more than happy to fill (and refill) your cup.

Mark Rigney is the author of the play Acts of God (Playscripts, Inc., 2008) and the non-fiction book Deaf Side Story: Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets and a Classic American Musical (Gallaudet University Press, 2003). His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and appears in The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Talebones, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, among many others, and an upcoming trilogy is slated to begin in Black Gate in 2011. His website, with links to many of his original stories, stage plays and the dreaded Anti-Blog, is www.markrigney.net.