Worlds Within Worlds: The First Heroic Fantasy (Part III)

This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor.

This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor.

In the first post, I considered how to identify a fictional otherworld. I suggested four characteristics, of which a story’s fictional world needed to have at least three to be a true otherworld: its own logic (which might involve, say, the existence of magic), characters who we identified as residents of another world than our own, a coherent history, and a coherent fictional geography. In the second post, I considered ways in which older fantasies were linked to reality — by being set in the past, or in a place beyond contemporary knowledge, or being established as a dream, or as a story within a story, or as a myth. I concluded by discussing what I felt was significant about the idea of otherworld fantasy.

Before going on to present my suggestion for the writer of the first otherworld fantasy, though, I’d like to take a closer look at some past fantasies I thought came very close to presenting self-contained otherworlds. These are works which I don’t think are true otherworld fantasies, but which other people might choose to see as such.

I’d like to begin by re-examining a part of my argument from last week, when I said that a myth represented a way of connecting fantasy to this world. I said that as far as I knew, a myth was designed to always shed some light on the real world; it served, in a way, to make the real fantastic.

Which is fair enough when you’re talking about people who are telling and retelling myths in which they believe. What about people who’re using mythic material they regard as fictional?

This question seems to me to break down into three different cases. In the first case, you’d have people collecting and transcribing or retelling a myth that somebody else believes. That doesn’t seem relevant to me here; effectively, that would be a story-in-a-story, a story that comes with a frame saying “here is something that someone else believes, or once believed.”

In the second case, you’d have people using somebody else’s myths as fantastical elements in their own stories. Consider, off the top of my head, Shakespeare having Hecate appear to the witches in Macbeth. I don’t think this is usually relevant either. While this would make a story a fantasy, you’d need to bring in an awful lot of mythic material for it to approach otherworld status.

But the third case, I think, is worth looking at closely. This is what happens when somebody who does not believe in a myth works extensively with mythic material, forming a new creative work out of the complete body of myth. Can that produce an otherworld?

Let’s look at a few examples. I’ll start with the Prose Edda, a collection of Norse myth. Not much is known definitely about its creation; it’s believed to have been written about 1220 by the Christian Snorri Sturluson, probably for the purpose of explaining poetic form in traditional Icelandic verse.

Let’s look at a few examples. I’ll start with the Prose Edda, a collection of Norse myth. Not much is known definitely about its creation; it’s believed to have been written about 1220 by the Christian Snorri Sturluson, probably for the purpose of explaining poetic form in traditional Icelandic verse.

Earlier Norse poetry was filled with riddle-like ‘kennings’ — instead of saying ‘gold’, for example, a poet might refer to ‘Freya’s tears’. But if you didn’t happen to know that the Goddess Freya wept golden tears, the reference would be lost. Snorri was faced with the problem of writing down the stories of the old Gods, along with some of the most common kennings, while also as a Christian definitively rejecting the heathen beliefs that had produced them.

The document Snorri produced, the Prose Edda, begins with a prologue in which he claims that the pagan creation myths represented only the best guess the pagans had for how the world came into being; Odin, ruler of the Gods, was actually the leader of a tribe of men who came to the north of Europe after the fall of Troy. The first section of the Edda, Gylfaginning, follows a king of Sweden named Gylfi (a legendary figure) as he travels to Asgard, the settlement of this tribe, the Æsir, and asks them several questions about the Gods and the creation of the world. The next section, the Skaldskaparmal, is broadly similar, except it follows a man named Ægir on his visit to Asgard; his questions have a lot more to do with the kennings, and no real ending to his story is given. The final section of the Edda, Hattatal, is a close examination of various kinds of metre.

The Prose Edda retells a number of pagan myths, from the creation of the world to the end of time. It also contains tales of magic and swordplay and struggle against evil, and of a great battle at the end of all things. Which certainly sounds like high fantasy, and indeed the book was a significant influence on writers like Tolkien, George MacDonald, Morris, and C.S. Lewis.

The myths describe the creation of the earth; it’s one of a series of nine worlds, made through the actions undertaken by Odin and his family. Assuming that as a Christian Snorri didn’t actually believe in the legendary material he was repeating, then isn’t he doing something similar to what Susanna Clarke did in Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell — creating a fantasy in which the supposedly real world is actually a fantasy analogue of reality?

Well, maybe. I don’t think so, though. I think that we’re meant to perceive Snorri’s human characters as people who actually might have existed in this world. Gylfi would have been recognised as a historical person, and Ægir (though the name is the name of a Norse God) is said to come from “an island which is now called Hlesey.” Moreover, Snorri carefully presents the myths as stories told by human beings called Æsir to other people, denying the myths the possibility of independent reality.

That framing technique, presenting the mythology as tales told, is key. Snorri goes out of his way in the Skaldskaparmal to say in his story that the Gods of Asgard are not Gods. In Anthony Faulkes’ translation: “Yet Christian people must not believe in heathen gods, nor in the truth of this account in any other way than that in which it is presented at the beginning of this book [i.e. the prologue], where it is told … how the people of Asia, known as Æsir, distorted the accounts of the events that took place in Troy so that the people of the country would believe that they were gods.” Snorri then spends a long paragraph firmly linking the Odinic Gods to Troy, and “debunking” some of the stories just told (“the Æsir did not like to admit that Oku-Thor had died as a result of one person overthrowing him in death even though such had been the case, and they exaggerated the story beyond what was true, when they said that the Midgard serpent suffered death there”).

So: the Prose Edda is meant to take place in this world, and Snorri went to considerable lengths to establish that he was writing something that happened to be a collection of tales people had been told, not true stories in their own right, thus making a frame for the fantasy. Are there other examples to look at?

Well, let’s skip forward in time a bit. In 1760 a Scotsman named James Macpherson created a sensation when he published prose translations of what he claimed was ancient Scots poetry. He followed this popular success with further prose-poems, an epic which he claimed had been written by a bard named Ossian centuries before, and which existed now as fragments in distant parts of Scotland. Luckily, he’d found a surviving manuscript.

Well, let’s skip forward in time a bit. In 1760 a Scotsman named James Macpherson created a sensation when he published prose translations of what he claimed was ancient Scots poetry. He followed this popular success with further prose-poems, an epic which he claimed had been written by a bard named Ossian centuries before, and which existed now as fragments in distant parts of Scotland. Luckily, he’d found a surviving manuscript.

As it happens, this appears not to have been true. Instead, it seems that while Macpherson did use some genuine Scots poetry in his “translations”, he transformed it freely into his own work.

The result was a series of long, incantatory, vaguely mythic tales about a Scots equivalent to the Irish Fenians. Macpherson’s poems are filled with war, ghosts, and doomed love, and for a few decades they were tremendously popular. In fact, they helped to trigger a fashion for collecting folk poems, ballads, and fairy tales which spread through much of Europe. Then, for whatever reason (presumably after it became clear how much Macpherson had invented), the vogue for the ‘Ossianic’ poems faded, and they were largely forgotten.

That’s too bad, I think. I find them interesting, if a bit rich, and an intriguing early fantasy fiction. But are they otherworld fantasy?

Well, they have a fantastic logic to them (things like ‘ghosts exist’), and the characters and peoples in the stories have a complex series of relationships and histories. But the geography is definitely the geography of this world, and the characters in the poems are meant to be understood as people of this world. So, no, but then neither are they that far away from William Morris’ works, either, I think.

Well, they have a fantastic logic to them (things like ‘ghosts exist’), and the characters and peoples in the stories have a complex series of relationships and histories. But the geography is definitely the geography of this world, and the characters in the poems are meant to be understood as people of this world. So, no, but then neither are they that far away from William Morris’ works, either, I think.

On the other hand, the interest in collecting folk poetry Macpherson helped to inspire continued on for some decades, under the influence of the movement called ‘Romanticism’. In fact, Romanticism wasn’t so much a movement as a vaguely-defined ‘spirit of the age’, which tended to celebrate the irrational, the magical, and the fantastic. Folk poetry was part of that, along with an interest in medieval romances and the ‘dark ages’ in general. England was one of the countries where Romanticism first flowered, but it soon spread across several other European nations as well. Eventually, Macpherson’s creative rewriting of folk poetry found a much more respectable counterpart.

Elias Lönnrot was a Finn who recorded the oral poems and narratives of his people, and worked them into a coherent epic called the Kalevala. First published in 1835, a revised and expanded version appeared in 1849. Lönnrot seems to have taken fewer liberties with his sources than Macpherson did with his, and the Kalevala quickly became hailed as the national epic of Finland. It has since inspired the compositions of Sibelius, and of many interesting heavy metal bands.

The poem begins with a creation myth, and moves on to tell the tales of several Finnish heroes as they search for mates and battle against the people of the North. There’s magic and war and, like the Edda, it was a significant influence on Tolkien. Is it an otherworld fantasy?

The poem begins with a creation myth, and moves on to tell the tales of several Finnish heroes as they search for mates and battle against the people of the North. There’s magic and war and, like the Edda, it was a significant influence on Tolkien. Is it an otherworld fantasy?

This is perhaps the most interesting case so far. The poem has its own magical logic, and it creates a history as it goes. The characters seem to be intended as Finns — but the geography is difficult to parse, and I understand there are still debates about where, exactly, ‘the North’ is meant to be, and who the people are that the heroes of the poem war upon.

I don’t think that confusion about geography is quite enough to count as creating an independent world for the poem. Certainly it seems counter-intuitive to think that Finnish myth could be seen as an otherworld fantasy. But I could see somebody who was especially determined try to make a case for it.

Still, I think in the long run myth represents a dead end in looking for otherworld fantasy before about two centuries ago. Even when the myth is not actually held to be true, it looks like it must include a geography based on the real world, and characters meant to be interpreted as people from a specific culture in the real world. So myth doesn’t really work as a ground for the sort of otherworld fantasy that I’m looking for.

Let’s move on from there, then, to consider a story of a type I haven’t mentioned in this series of posts so far. I’d like to talk about a play.

When you look at Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, around the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth, you see lots of fantasies. In Shakespeare alone, there are a ton: The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream are obvious, but even history plays had moments of magic in them (like the witches in Macbeth, or Joan of Arc summoning demons in Henry VI Part One). Other playwrights of the time also had no hesitation in putting magic on the stage, as in George Peele’s fairy-tale-like The Old Wives Tale (which lacks the distinctive history and geography of a high fantasy world), or John Lyly’s Endymion, which is worth mentioning here if only because it began with a wonderful prologue giving a tongue-in-cheek defense of fantasy:

“Most high and happy Princess, we must tell you a tale of the Man in the Moon, which, if it seem ridiculous for the method, or superfluous for the matter, or for the means incredible, for three faults we can make but one excuse: it is a tale of the Man in the Moon.

“It was forbidden in old time to dispute of Chimæra because it was a fiction: we hope in our times none will apply pastimes, because they are fancies; for there liveth none under the sun that knows what to make of the Man in the Moon. We present neither comedy, nor tragedy, nor story, nor anything but that whosoever heareth may say this: Why, here is a tale of the Man in the Moon.”

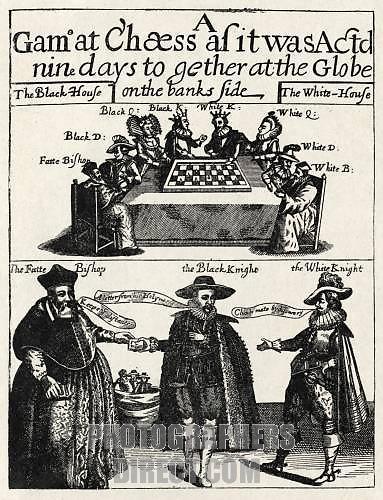

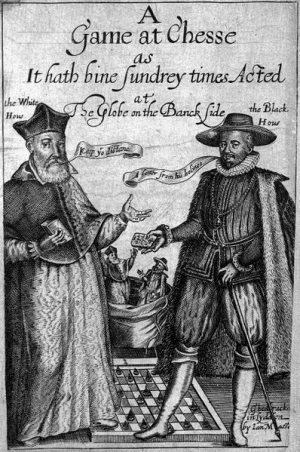

But Endymion, though a remarkable version of the myth, is not the play I want to talk about. Instead, I want to focus on a later, and superfically less fantastic, work: A Game At Chess, by Thomas Middleton, from 1624.

But Endymion, though a remarkable version of the myth, is not the play I want to talk about. Instead, I want to focus on a later, and superfically less fantastic, work: A Game At Chess, by Thomas Middleton, from 1624.

It’s not a fairy tale. It’s closer to a direct political allegory. We follow the machinations of two courts, the White and the Black, as the Black schemes against the White. The characters are chess pieces: the White King, the White Knight, the Black King, and so on. The White court is meant to represent Protestant England, with the White King as King James; the Black are the forces of Catholicism, with the Black King as Philip of Spain.

The play follows the rules of an actual chess game — mostly. But one of the pieces switches sides, while other pieces regret their actions or connive at seducing an enemy pawn. So the pieces are actually real people.

Well, again, mostly. There is one notable exception. Unlike most plays of the era, nobody dies. Instead, when a character is removed from the game, they’re sent to “the bag” — that is, the bag where discarded chess pieces are kept once they’re taken from the board. (The bag could presumably be dramatised as a prison, but seems to be more strongly implied as a representation of death.)

Interestingly, the idea of the bag shows up as more than a stage metaphor; it’s also a figure of speech for the characters — “damn him / Into the bag for ever,” says one of them. They’re aware of the bag. It’s a part of the logic of their world. And this suggests that those characters are something other than one-for-one stand-ins for real people and real countries.

That’s logic and culture, two of the four characteristics. What about history and geography? Well, the White and Black courts don’t seem to have a thoroughly-developed relationship to each other, but you could certainly argue a history of enmity, and some mention of specific actions (a black pawn castrated a white pawn before the play began, for example). Geographically … things are a bit more interesting.

We seem to be in a Clarke-like alternate Europe. There’s a Catholic Church, and a Europe that we recognise. But almost by defintion, there must be something more to it. There are references to a Black Kingdom and a White Kingdom. The Black and White courts occupy two Houses on the stage, but we get no more specific stage setting than that.

What we do have is the stage itself. We can see a geography right there before us, containing the two houses, and a field between the houses. Arguably, then, the magic performance space of the stage creates the fantastic geography that in turn creates a world.

What we do have is the stage itself. We can see a geography right there before us, containing the two houses, and a field between the houses. Arguably, then, the magic performance space of the stage creates the fantastic geography that in turn creates a world.

It’s a difficult argument in many ways, but I can just about see it being made. The real problem here is that there’s also a frame around the story: it begins with an introductory scene, in which Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, is depicted as railing against England before waking up his servant Error, who then describes the dream he had about the struggle between England and Catholicism — which is the body of the play. So the fantasy world again collapses into a dream.

But I’ve mentioned it here because the play’s also a useful reminder that sometimes frames don’t always work. Because on the one hand, in the logic of the play, the frame’s perfectly coherent: it’s a dream, and that’s that. But on the other … the play was a play. It was performed on a stage. And when it was, something interesting happened.

In the seventeenth century, certain things were not permitted in the English theatre. To begin with, you couldn’t present a living European monarch on stage. Which is probably why Middleton experimented with his unusual quasi-allegorical drama; he could bring on James and Philip without them actually being James and Philip. But how did the audience react to them? How were they presented? Were the actors meant to mimic the real-life originals of the characters?

Well, at the time, theatre companies often bought up old clothes from rich or noble people in order to properly costume their actors for high-class roles. Now, one of the characters in A Game at Chess, the Black Knight, was based on the former Spanish ambassador to England, the conde de Gondomar. And evidently, for the play’s first production, the troupe that put on the play bought some of Gondomar’s clothes for the actor playing the part of the Black Knight.

Interestingly, when the play was submitted for approval before being produced, the Master of the Revels gave it the all-clear. He saw no problem with it — presumably, he responded to it as a fantasy. For him, the frame was less significant than the matter of the drama.

The Spanish ambassador of the time, however, was not so charitable. He complained, and the production was soon shut down (despite being quite popular; most of the audience, it seemed, got the allusions).

Ultimately, A Game at Chess is, I think, an interesting movement toward the creation of an independent secondary world, and an interesting study of how people respond to fantasy, as well as how to evade censorship by the use of fantasy and allegory. But not an otherworld fantasy itself.

Wait, though. Isn’t there another Elizabethan allegory that might be worth considering here? Something that looks much more like high fantasy than Middleton’s play? Something much more famous? Something, in fact, that’s one of the greatest literary works in the English language?

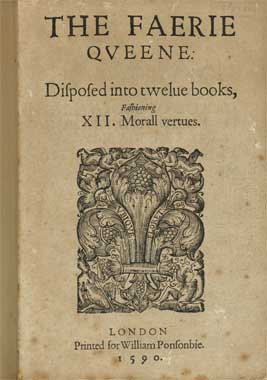

Well, yeah. In the 1590s, Edmund Spenser published a long poem called The Faerie Queene. The poem, as it exists today, consists of six books plus a bit (the Mutabilitie Cantos, if you want to be precise). Spenser had projected the complete poem to be twenty-four books, with each book examining a different virtue. Even in its fragmented form, though, The Faerie Queene is one of the longest poems in the English language. And it is quite a good one.

Well, yeah. In the 1590s, Edmund Spenser published a long poem called The Faerie Queene. The poem, as it exists today, consists of six books plus a bit (the Mutabilitie Cantos, if you want to be precise). Spenser had projected the complete poem to be twenty-four books, with each book examining a different virtue. Even in its fragmented form, though, The Faerie Queene is one of the longest poems in the English language. And it is quite a good one.

Although it has a detailed allegorical meaning, the story’s filled with color and adventure. It’s based on medieval romances, and on the Italian fantasies about Charlemagne’s paladins: it follows a number of knights (one per book, each the allegorical symbol of a certain virtue) as they wander in a magical wood, encountering evil wizards, Saracens, monsters, and each other.

Is it an independent fictional world? Well, clearly the world of the poem has its own logic, with magic, dragons, Gods, and spirits. The characters learn about the backgrounds of the threats they face, and about things that were done in the past that shape the tale, so that’s history. Specific places in the wood recur, and there are named places beyond the world, such as Cleopolis, the capital of Gloriana the Faerie Queene. So that’s three out of four characteristics for an otherworld right there.

What about how we identify the characters, and what about frames connecting the story to the real world? Well. This is where it gets odd.

To start with, it’s not a dream, like most allegories. So there’s that. But it is an Arthurian story; a young Prince Arthur with a diamond shield is a recurring figure in the poem, usually appearing to rescue the knights who are the main characters in each book whenever they get into trouble they couldn’t handle themselves. It seems that, had the poem been completed, Arthur would have ended up marrying Gloriana.

So is the poem a kind of land-of-fable England? Well, note that the hero of the first book, the Redcrosse Knight, who represented holiness, has another name. A holy man prophesies for him that there “is for thee ordaind a blessed end: / For thou emongst those Saints, whom thou doest see, / Shalt be a Saint, and thine owne nations frend / And Patrone: thou Saint George shalt called bee, / Saint George of merry England, the signe of victoree.” (Book I, Canto 10, stanza 61)

So there’s a specific reference to England, along with the figure of Arthur. In fact, a little later (Book I, Canto 11, stanza 7), Spenser asks of his muse that she “lay that furious fit aside, / Till I of warres and bloudy Mars do sing: / And Briton fields with Sarazin bloud bedyde, / Twixt that great faery Queene and Paynim king, / That with their horrour heuen and earth did ring, / A worke of labour long, and endlesse prayse: / But now a while let downe that haughtie string, / And to my tunes thy second tenor rayse, / That I this man of God his godly armes may blaze.”

The “man of God” is the Redcrosse knight; Spenser’s asking his muse to not inspire him with fury, which is appropriate for war poetry, because he wants to talk about how great his hero is. More specifically, he asks his muse to hold off on the fury, until he needs to describe the battle between the Faerie Queene and the King of the Paynims, which will take place in “Briton fields”.

The “man of God” is the Redcrosse knight; Spenser’s asking his muse to not inspire him with fury, which is appropriate for war poetry, because he wants to talk about how great his hero is. More specifically, he asks his muse to hold off on the fury, until he needs to describe the battle between the Faerie Queene and the King of the Paynims, which will take place in “Briton fields”.

Presumably, had Spenser gotten around to writing about the war between the Queene and King (he didn’t), it would have been the big climax for his epic. Which is interesting, because having a major clash of armies for the big finish to a story sounds very like high fantasy; and, if we’re talking about fantasy flavor, the Encyclopedia of Fantasy notes that Spenser “devised his own mock-archaic diction, with many wilful misspellings and neologisms. Thus he was the first writer to create his own language to convey the distinct atmosphere of a fantasy world.”

Still, there is that specific reference to “Briton fields”. It certainly seems that Spenser’s talking about England here. On the other hand, his King Arthur and Saint George are decidedly off-model. And I don’t recall a battle between elves and pagans in most books about English history. Hey — isn’t this getting us into the territory of an alternative world?

Does The Faerie Queene present an independent alternative fantasy world in the manner of Susanna Clarke? Well, besides the fact that I can see some similarities to Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell in the way it talks about England, and the way it uses English history, in general, it seems like an arguable point.

But I also think that Spenser meant for his poem to connect up to the real world as we know it (or, at least, as his audience knew it). In Book III, Canto 3, some characters are given a vision of the future, which specifically leads up to Spenser’s time, and refers to events happening around him. So we can say that Spenser intended the poem to be set in the distant past, albeit a past when magic worked, and a past which didn’t really tie in with the actual past, even as it was understood in his time. In a sense, then, it resembles Tolkien’s Middle-Earth — a thought which would have annoyed Tolkien, who didn’t particularly care for Spenser’s work.

Okay, so Spenser’s allegory isn’t quite high fantasy, or at least isn’t quite wholly independent of the real world. But, frankly, authorial intention aside, it’s really easy to read it as in independent fantasy world, a weird fusion of the settings of Clarke and Tolkien. It happens not to be what Spenser had in mind, though, and would not be a way of reading his poem that he would have understood. This is significant to me, as I’m looking for somebody who created something that was, or probably was, intended to be read as its own world. So not The Faerie Queene, not quite.

Frankly, allegory still looks pretty interesting with respect to the possible development of secondary worlds, since almost by definition the world of an allegory is a world that is not this one. Medieval plays like The Castle of Perseverance seem to be getting close to a fantastic otherworld (though still anchored firmly in the real). Are there any allegories that are completely independent of the real world? Are there any allegorical fables that aren’t framed as a dream?

Actually, yes, quite a few. Most of them use some other kind of frame, but one may be worth noting here, a long prose work, standing near the start of the tradition of the English novel. John Bunyan, who wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, also wrote a book in 1682 called The Holy War, in which the evil Diabolus corrupts the town of Mansoul, and leads it in rebellion against its rightful lord, Shaddai. But Shaddai sends his son Emmanuel to reclaim the town …

Actually, yes, quite a few. Most of them use some other kind of frame, but one may be worth noting here, a long prose work, standing near the start of the tradition of the English novel. John Bunyan, who wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, also wrote a book in 1682 called The Holy War, in which the evil Diabolus corrupts the town of Mansoul, and leads it in rebellion against its rightful lord, Shaddai. But Shaddai sends his son Emmanuel to reclaim the town …

The book depicts a world with its own geography, history (the background of Mansoul and its establishment by Shaddai is given in detail), logic (there are giants, for example, and Diabolus turns invisible), and distinctive culture. Four out of four characteristics. Does it exist in a world all its own?

In fact, it’s framed as a traveller’s tale — but a very peculiar one. It begins: “In my travels, as I walked through many regions and countries, it was my chance to happen into that famous continent of Universe. A very large and spacious country it is: it lieth between the two poles, and just amidst the four points of the heavens. It is a place well watered, and richly adorned with hills and valleys, bravely situate, and for the most part, at least where I was, very fruitful, also well peopled, and a very sweet air.”

It’s a traveller’s tale, but you wonder where the traveller was from. Not only does he easily refer to a nonexistent continent, but he goes on to relate a tale which anybody familiar with Christian myth and theology would easily recognise, and makes no mention of that fact. It’s tempting, frankly, to view the whole thing as the tale of a traveller from another world — since the narrator makes no reference to any actual place in this one.

It’s tempting, but in my first post I did put forward the fantasy equivalent of Occam’s Razor: don’t multiply worlds unnecessarily. Is it necessary to imagine another world here, though? I can see the argument that it is. It may actually be even easier to read The Holy War as requiring an independent fantasy world than it would be to read The Faerie Queene as such.

Occam’s Razor aside, though, I think the structural gambit Bunyan uses to open the book suggests that it’s not quite there. He’s using a traditional frame, however attentuated, to link his allegorical world to the real world. The book is certainly a fantasy. But I don’t think I’d quite accept it as an otherworld fantasy myself.

Finally, I want to take a look at a form I haven’t mentioned much so far: the fairy tale. Important fairy tale collections appeared in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in the later seventeenth century French writers such as Madame d’Aulnoy and Charles Perrault began publishing more literary, satirical tales; this approach continued through the eighteenth century in France. Around the beginning of the nineteenth century, the impetus of Romanticism led to an increase in interest in fairy tales in Germany, in both their popular forms (for example, in the famous collection by the Brothers Grimm) and their more polished literary forms (such as the work of E.T.A. Hoffmann, whom I mentioned in my previous post).

Finally, I want to take a look at a form I haven’t mentioned much so far: the fairy tale. Important fairy tale collections appeared in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in the later seventeenth century French writers such as Madame d’Aulnoy and Charles Perrault began publishing more literary, satirical tales; this approach continued through the eighteenth century in France. Around the beginning of the nineteenth century, the impetus of Romanticism led to an increase in interest in fairy tales in Germany, in both their popular forms (for example, in the famous collection by the Brothers Grimm) and their more polished literary forms (such as the work of E.T.A. Hoffmann, whom I mentioned in my previous post).

I don’t think most fairy tales are possible otherworld fantasies, in the sense that I mean the term. To begin with, the stories are often specifically placed in this world. But even when that’s not clearly established, when no specific setting is given, traditional fairy tales still don’t seem to me to have the sense of place, the fantastic history and geography, needed to establish a convincing otherworld. And the characters, I think, are meant to be read as inhabitants of this world.

But I want to note that this is an area where I’m uncomfortably aware I’m not particularly well-read. And I do think that the early nineteenth-century fairy tale strongly influenced fantasy later in the century, and indeed beyond. So I note this is an area that may be worth further investigation.

I’d like to end this post, in fact, considering the situation of fantasy in the first half or so of the nineteenth century. The century began strongly with Romanticism, as I’ve mentioned. Fantasy could be found in a number of different forms. There were fairy tales, and folk tales, many of them collected now for the first time. There was also the Gothic novel, a form of writing that became popular in the 1790s and continued throughout the early decades of the next century. Gothic was, as you might expect, a kind of horror-oriented storytelling, frequently set in the past, often involving ghosts and the supernatural.

Primarily, though, there were the Romantic poets themselves. Writers like Blake, Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were turning out fantasies in verse, many of them with a Gothic flavor.

According to the standard literary chronology, Romanticism and the Gothic faded after the first two or three decades of the nineteenth century; the great English Romantic poets died or declined, and the Gothic novels dried up. Then, at about the middle of the century, writers like John Ruskin and, especially, George MacDonald revived fantasy in the form of fairy tales for children.

MacDonald, a friend of Morris, was inarguably a key figure in the development of modern fantasy. Still, when he created otherlands, they were typically either not distinguished by a specific geography or history (consider MacDonald’s excellent The Princess and the Goblins, where no terrain feature seems to have a name), or used some variety of the framing techniques we’ve already seen. His 1857 book Phantastes, for example, mixed dream and reality in an intriguing way, presenting a fantasyland which seemed to bleed over into this world.

But what about outside of England? As we’ve seen, fairy tales were common elsewhere in Europe; it might be more accurate, then, to say that MacDonald revived the fairy tale in English. Romanticism had continued in other countries, and France had developed an interesting tradition of the fantastique before MacDonald started writing, with writers such as Charles Nodier and Théophile Gauthier. They, like Hoffman, produced fantasy tales that involved otherworlds, though as far as I can tell, these fantasies never quite left the real world behind.

Then again, one could debate the statement that the Gothic novel died in the early nineteenth century. Certainly the Brontë sisters were soon writing a kind of de-supernaturalised Gothic — and the Brontës are fascinating in this context, because as children they created what psychologists have started calling paracosms: invented worlds, with their own geography and history. The Brontës’ brother Branwell was given some toy soliders when he was a boy, and as the children played with them, they developed whole worlds out of the stories they told about the soldiers. The sisters even wrote tales about these worlds as they grew older.

Then again, one could debate the statement that the Gothic novel died in the early nineteenth century. Certainly the Brontë sisters were soon writing a kind of de-supernaturalised Gothic — and the Brontës are fascinating in this context, because as children they created what psychologists have started calling paracosms: invented worlds, with their own geography and history. The Brontës’ brother Branwell was given some toy soliders when he was a boy, and as the children played with them, they developed whole worlds out of the stories they told about the soldiers. The sisters even wrote tales about these worlds as they grew older.

Their stories still seem to have kept a real-world link, though. The fantasylands the Brontës created were set in this world, in Africa or on a Pacific Island. So not quite an independent fantasy world, but certainly moving in that direction, at a time when the Gothic influence was still around, when Romanticism and fantastic fiction was still a force in Europe, and when the fairy tale was about to find new life in England.

It is perhaps not surprising that it was in this atmosphere that a writer created what I think was the first otherworld fantasy.

I name that writer, and make my case for the importance of the fantasy, here.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

[…] thinking about that question here, and my final answer is here. Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” […]

[…] Faerie Queene, or the Epic of Gilgamesh, or … you get the picture. I happen to agree with our own Matthew David Surridge that Phantastes is likely not the first pure fantasy novel, for the fact that, although it involves […]