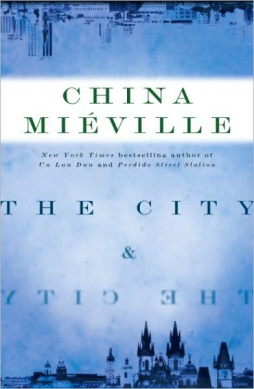

Of Policed Identities and Public Urination: A Review of The City & The City

The City and the City is a murder mystery. That is the first thing. Miéville makes it perfectly clear: the book explicitly follows the rhythms of this genre, the steps as strictly defined as the rules of a sonnet: the death, the jaded, world-weary but still tender-hearted investigator, the discovery that the victim was not quite what she seemed, the additional deaths, the dead ends and red herrings, the gathering momentum, the Explanation between murderer and detective, slotting all the puzzle pieces together in front of all the characters assembled, the wry denouement.

The City and the City is a murder mystery. That is the first thing. Miéville makes it perfectly clear: the book explicitly follows the rhythms of this genre, the steps as strictly defined as the rules of a sonnet: the death, the jaded, world-weary but still tender-hearted investigator, the discovery that the victim was not quite what she seemed, the additional deaths, the dead ends and red herrings, the gathering momentum, the Explanation between murderer and detective, slotting all the puzzle pieces together in front of all the characters assembled, the wry denouement.

And the fact that an almost superciliously correct mystery can blend so perfectly with the surreality of a fantasy of superimposed cities is due to the fact that, as Miéville says in the Random House Reader’s Circle interview at the end of the book, the crime novel is “at its best, a kind of dream fiction masquerading as a logic puzzle. All the best noir – or at least I should say the stuff I like most – reads oneirically. Chandler and Kafka seem to me to have a lot more shared terrain then Chandler and a true-crime book.”

Spoilers below the cut. Don’t read them. It just tied for the 2010 Best Novel Hugo – just go read the book!

To spoil the magic: Ul Qoma and Beszel are two cities which share one physical space, in which the boundaries of the city are defined not by different streets but by what the inhabitants of the cities are willing to see and not see. In Beszel, you learn to not see the buildings you pass that belong to Ul Qoma; on Ul Qoman streets, you dodge the Besz traffic that shares the same physical asphalt without ever acknowledging it. Dream logic: Inspector Borlú of Beszel, having cleared his visa and done the paperwork to cross the conceptual border to meet with his counter part in Ul Qoma, finds that “”It was quickly obvious that he lived within a mile, in grosstopic terms, of my own house.” Grosstopic: not geography, a discipline which includes names and functions, just its crudely undeniable physical aspect. A dream word? One that only makes sense in Illitan, or, of course, Besz?

Of course not. In fact it’s very difficult to discuss this book without immediately giving in to the temptation to engage in hand-wringing about the unseeing which city dwellers daily practice upon [the homeless / poverty / prejudice / rogue nuclear states / backyard chickens / whatever] for which The City and The City could be construed as a clever metaphor. A more nuanced view might refer to Jane Jacobs’ studies of how people live and work in cities, and the ways in which we must delineate our lives with the boundaries of our attention when we live too close together to do it with the boundaries of geography.

But whether or not you approve, it’s obvious: unseeing, we do it, you and I. No, the only true fantasy element of this book is Breach: the shadow police force that enforces the situation known as Cleavage. (Cleavage: 1) splitting apart; 2) adhering together; 3) a condition that powerfully attracts attention, and clearly Miéville revels in the ambiguity of the phrase.) Breach is secretive, all-powerful, answerable to no one, and enforces zero tolerance of any breaching of the separation between the cities.

“It works because you don’t blink. That’s why unseeing and unsensing are so vital. No one can admit it doesn’t work. So if you don’t admit it, it does. But if you breach, even if it’s not your fault, for more than the shortest time… you can’t come back from that.”

“Accidents. Road accidents, fires, inadvertent breaches…”

“Yes. Of course. If you race to get out again. If that’s your response to the Breach, then maybe you’ve got a chance. But even then you’re in trouble. And if it’s any longer than a moment, you can’t get out again. You’ll never unsee again.”

But this is a virginity myth just as fantastical as the book’s layered conceit of shadowy figures pulling strings behind the scenes. Once the walls of your attention have been penetrated, they’ll never be any good again? No, that’s not how social enforcement works: it’s ubiquitous and relentless, and it comes from all sides, and if you break it in one place it just heals itself over, even in your head.

I was stuck in traffic the other day. No, it deserves a capital letter: I was stuck in Traffic. I was in the middle of a freeway, miles from the next exit. I had shut off my car’s engine and taken off my shoes and pulled out my phone to bitch about the situation on Twitter. I had to piss like a racehorse.

Grosstopically, I was about six inches away from the nearest place where I could have conveniently peed, which would have been outside of my car. If I’d been feeling modest, I could have abandoned the car and gone behind the bushes on the side of the road, which would have been maybe thirty feet away. Relief was about two minutes away, grosstopically. But geographically, in actual fact, it was forty-five minutes before I got to a place where I could relieve myself. And let me make it clear: those were forty-five minutes of suffering.

And I chose to endure that suffering rather than break the boundaries of conceptual geography and pee on the freeway. I do not go in fear of Breach. If I’d peed on the freeway, shadowy figures would not have come and taken me away. Nor would I have irrevocably violated the boundaries in my head and from then on been unable to prevent myself from peeing freely everywhere I felt the urge. There’s no need for these threats to keep me in line, or you. Violate the boundaries and they heal themselves. Breach is the fantasy of a hidden city. In real life Breach is in your head.

It’s a great book, all right. A REAL Urban Fantasy.