The Weird of Cornell Woolrich: “Kiss of the Cobra”

No, this isn’t a review of the Ken Russell film The Lair of the White Worm. The poster just fits so well with Cornell Woolrich’s 1935 story “Kiss of the Cobra” that I had to use it. You would almost think Russell was adapting Woolrich, not Bram Stoker.

No, this isn’t a review of the Ken Russell film The Lair of the White Worm. The poster just fits so well with Cornell Woolrich’s 1935 story “Kiss of the Cobra” that I had to use it. You would almost think Russell was adapting Woolrich, not Bram Stoker.

My three previous installments exploring the fantasy and horror tales of suspense author Cornell Woolrich have all looked at classic works from his typewriter: “Jane Brown’s Body,” “Dark Melody of Madness,” and “Speak to Me of Death.” However, Woolrich was a prolific pulpster, and sometimes he pounded out sub-par work because the hotel room bill had to be paid. Any Woolrich fan can whip out a list of the writer’s suspense stories that simply made him or her cringe—and not positively. I’m as hardcore a Woolrich aficionado as you will likely find, and even I have to admit that some of his lesser stories are dreadful. His exploration of vampires, one of his potentially intriguing side trips into the supernatural, “Vampire’s Honeymoon” (later revised and retitled “My Lips Destroy” so Woolrich could sell it as a “new” piece), is the single most clichéd work about vampires I’ve ever read. Only the staking of a vampire using a broken hockey stick makes it remotely interesting. I can’t imagine Woolrich spent more than two hours cranking it out and then sending it off. It’s an indication of the power of Cornell Woolrich’s name on the front of pulp magazines of the time that it sold on its first try.

But some of Woolrich’s mid-level work deserves attention, and “Kiss of the Cobra” falls solidly into his opus of “weird stories.” It examines the concept of “foreign other” with fantasy displays that hint at black magic, contains richly sensual prose, and has a liminal sense of a were-creature. The suspense and hard-boiled crime aspects are also well executed, even if the mesh of the two sides isn’t that smooth. Much greater work was to come, but with all its flaws (such as the standard pulp era’s Euro-centric view of India and a protagonist given to generic wise-crack dialogue) the story remains worth visiting for horror and suspense enthusiasts.

“Kiss of the Cobra” comes early in Woolrich’s pulp crime canon. After an abortive career as a mainstream novelist ended with the financial failure of Manhattan Love Song in 1932, Woolrich went through a dry-spell, only to abruptly re-emerge in 1935 writing stories for the popular crime magazines and beginning a creative run that would last until 1948, when the will and the well went dry. His first crime story sale was “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair” for Detective Fiction Weekly, a top-selling pulp that would remain Woolrich’s most dependable market. Although no stellar piece of work, “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair” shows many of its author’s favorite themes and devices: vivid portraits of Depression-era poverty, a weird murder method (a killer dentist who puts poison in his patients’ fillings), and a race-against-death finale.

Dime Detective published “Kiss of the Cobra” in its 1 May 1935 issue, the sixth of Woolrich’s suspense stories to appear in the wood pulp pages. Between it and “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair” came “Walls That Hear You,” “Preview of Death” (another “weird murder method” story), “Murder in Wax,” and “The Body Upstairs.” He also sold a romance yarn to Breezy Stories, “Spanish—And What Eyes!” The crimes stories all show an author easing his way into his new craft; none are classics in his canon, but none are wastes of time either.

Relatively, “Kiss of the Cobra” was Woolrich’s best pulp short at the time of publication. He would beat it soon after with “Dark Melody of Madness” (Dime Mystery, July 1935), which shares some of “Kiss of the Cobra”’s themes of “foreign horror.” It moves rapidly with present tense writing (Woolrich liked to use the immediacy of present tense at a time when it was rare) and its clipped, tough-guy first-person narration. The clash between the noir detective style and fantasy horror descriptions is an odd one, leading to some overwrought silliness, but the story has kick and a great finale that is quintessentially Woolrichian.

The narrator is Charlie Lawton, an L. A. homicide detective whose boss forces him into a convalescence trip to the San Bernardino Mountains. Charlie goes to stay in his father-in-law’s cabin (no electricity, no telephone, of course) along with his wife Mary and her twenty-year-old brother Vin. There’s one other guest: Charlie’s father-in-law brings his new wife Veda, fresh off the boat from India. And . . . she’s a sinister snake woman! Nooooooo!

Veda does initially look human and very beautiful, but Woolrich hardly waits a few sentences before he lavishes her with as much ophidian horror prose as he can:

Then, when we all sit down and I happen to notice how she’s sitting, all the short hairs on the back of my neck stand up. She’s sort of coiled around in her chair, like there were yards and yards of her. One arm is looped sinuously around the back of the chair, like she was hanging from it, and when I pretend to drop my napkin and look under the table, I see both her feet twined around a single chair-leg of being flat on he floor. But I tell myself, “What the hell, they probably sit different in India than we do,” and let it go at that.

This puts us deep into the stereotypical “Other” of pulp literature, where people from the east are untrustworthy and closer to a primordial and atavistic magic that it were best for the White Man not to meddle with, a theme identical to that in “Dark Melody of Madness,” although not as intelligently or ambiguously approached. Woolrich has here made a literal version of the femme fatale, a “spider-woman” who is actually a snake-woman.

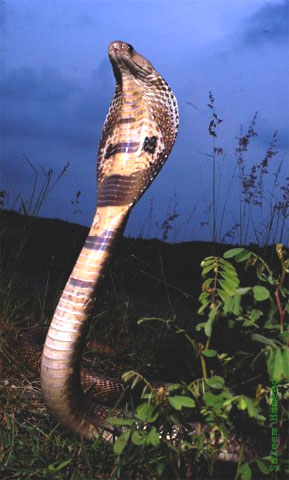

The snake parallels don’t let up, and Charlie never passes up an opportunity to wonder at the scaly, sinuous appearance and even weirder behavior of Veda, such as watching her slink around the floor of her room when she thinks she’s unseen and lap at a bowl of milk as if she had a forked tongue. It’s absurd, but Woolrich’s writing style carries the reader along anyway; the loathing for snakes is something deep in most people, and the author exploits it.

The snake parallels don’t let up, and Charlie never passes up an opportunity to wonder at the scaly, sinuous appearance and even weirder behavior of Veda, such as watching her slink around the floor of her room when she thinks she’s unseen and lap at a bowl of milk as if she had a forked tongue. It’s absurd, but Woolrich’s writing style carries the reader along anyway; the loathing for snakes is something deep in most people, and the author exploits it.

Soon after Veda’s arrival, Charlie’s father-in-law dies a horrid death in a spasmic seizure that leaves his body far too stiff for standard rigor mortis. Charlie brings in the police and uses his far-flung law enforcement prestige to order an immediate autopsy on the body; he has suspicions that an exotic poison caused the old man’s death and Veda is the culprit. The toxicology report comes back that the poison was cobra venom, but since there’s no sign of a bite anywhere on the old man’s body or any wound where the poison might have been introduced into the bloodstream, Charlie has nothing he can use against Veda.

Then another death occurs, this one happening in a frenzy that Woolrich works to perfection. Charlie latches onto Veda’s method, which involves poison lipstick, a pet cobra, and cigarettes. Alone in the house with the snake-woman, Charlie confronts her in a genuine nail-gnawer climax centered on a duel to the death . . . with cigarettes!

(Woolrich was a life-long smoker, but every time cigarettes are the focus in his work, they are always instruments of death. Sad self-awareness, Cornell?)

The supernatural angle remains an enigma on the edges of the story, a tempting gloss that adds a shiver to what would otherwise be a “weird murder method” yarn. Charlie cannot decide if Veda is a woman who has adopted the snake as her model through a cult, or if she is truly partially snake. “Maybe her mother had some unspeakable experience with a snake before she was born.” Unspeakable is right . . . Cornell, what are you implying? Ah, on second thought, don’t answer that. Charlie decides that, whatever Veda is, she’s a threat to the whole west coast if she gets away with the murders that will hand the old man’s fortune to her. Like many a Woolrich cop, Charlie has no problem using entrapment and brutal methods to get results.

Poison cigarettes and snakes would re-appear in Cornell Woolrich’s fiction in two later stories that are both among his best, and were probably starting to germinate in his mind when he was typing out “Kiss of the Cobra.” The archetypally titled “Cigarette” (Detective Fiction Weekly, 23 January 1937) concerns a mob hit using a cigarette laced with poison—and which ends up in the wrong hands and starts getting passed around the dregs of New York City, waiting for some innocent loser to light up and die. “Mind over Murder” (Dime Detective, May 1943; also reprinted as “A Death is Caused”) is a feverish nightmare about a woman living in the tropics trying to use her husband’s phobia of snakes to kill him—and it backfires bloodily. This was one of the first Woolrich stories I read (in the collection Angels of Darkness) and the first I remember that absolutely astounded me and had me shaking when I put it down. The shivers and tension inside “Kiss of the Cobra” are pumped to levels of sweat-soaked palsy here, and the ending is Woolrich at his illogically bizarre best.

“Kiss of the Cobra” has seen a few reprints. Like the other weird stories I’ve looked at in this series, it is part of collection The Fantastic Stories of Cornell Woolrich (a pricey little monster to find), and it also appears in Darkness at Dawn, which brings together all the crime stories Woolrich wrote during the early years of 1934 and 1935, including “Dark Melody of Madness.” I hope upcoming pulp horror anthologies will spread the net wide and snatch this one up: there’s more pulp terror out there than just what was published in Weird Tales, Strange Tales, and Unknown.