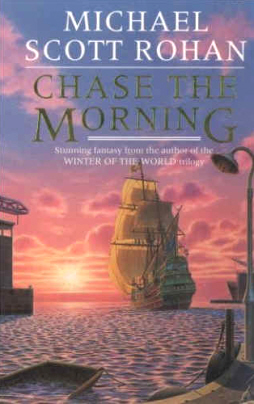

A review of Chase the Morning, by Michael Scott Rohan

Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . .

Steve is a very normal man, perhaps even a bit boring. He works at an English shipping company, handling inventories and looking forward to a career in politics once he climbs the business ladder as far as it will take him. One day, for no particular reason, a sudden fit of discontent sends him down to the docks looking for something different, perhaps a restaurant he hasn’t visited. In an alley, he sees a man being attacked . . .

Chase the Morning, by Michael Scott Rohan, doesn’t have all that much in common with modern urban fantasies like The Dresden Files. It does, however, feature a magic world hiding in the shadows and back streets of this one, so it may fit the category. The setting of Chase the Morning is easily my favorite part of the book — not because the rest of the book is bad, but because the setting touches my sense of wonder.

It’s nicely built up, too. The man Steve rescues is named Jyp, and as Steve’s wounds are stitched up in an old-fashioned gaslit pub, Jyp casually discusses his ship’s exotic cargo: black lotus, conqueror root, merhorse hide. But the pub proves elusive the next time Steve searches for it, the sailing ships he saw at the dock don’t exist, and as for the cargo, Steve actually finds it in his computer — on a ship from 1868. Ass he slips in and out of the mundane world, he keeps seeing an illusory landscape in the clouds — the same landscape. The magical world starts intruding into Steve’s world, to find out who he is and why he’s interfering; this culminates in the kidnapping of his secretary, Clare, by not-quite-human savages called Wolves. In search of Clare, in search of Jyp’s help, he manages to locate the magical version of the docks, the one that’s packed with sailing ships from all eras. And then, too desperate to be skeptical, he watches a ship sail off into the sky, into the landscape of clouds.

It seems that around our safe, solid world, there exists a realm called the Spiral, full of myths, magic, and ships. The idea is that too much mundanity tends to make people drift back into the Core — our world — and so the Spiral is populated largely by roveovers of one kind or another. This includes pirates, of course; the Age of Sail feel of the story wouldn’t be the same without them. Also, it’s possible to live a very long time in the Spiral (“you live, essentially, until you run out of things to live for”) so some of the characters are quite old indeed, and starting to distill into more powerful, mythic versions of themselves.

To recover Clare, Steve charters a ship and crew and sets out for the Caribbean, chasing the Wolf ship. Of course, the Spiral version of the Caribbean includes the voudoun gods, who seem to be taking an interest in the plot. In the meantime, we find out more about Steve, an empty man with an empty life, who left the woman he loved in college simply because she would have been inconvenient in his planned political career. Steve, we learn, is chasing desperately after Clare because their casual working relationship is the closest thing he has to a real human connection. Everything else is sterile.

I must admit, I like the mystery and the high adventure parts of Chase the Morning more than the character-building. At the beginning, for instance, we’re told that Steve feels unexpectedly at home with Jyp and his colleagues, but it feels forced to me. Similarly, Steve’s self-examination is mostly prompted by searching questions by Mad Mall, a woman who invites herself onto the quest because, as a quasi-paladin figure, she can’t resist a good fight for a good cause. Mall seems to know exactly the right questions to ask, and Steve gives up his rationalizations a little bit too easily, and it all felt a little clunky.

Still, that wasn’t what bothered me about this book. What bothered me about this book was a pattern of — for lack of a better word, I’d say racial clumsiness. Please note, I’m definitely not saying that Michael Scott Rohan is a racist; I’m certain he isn’t. But the writing occasionally hits a wrong note. At one point, for instance, there are various black magic talismans left in Steve’s office. His colleague Dave, a black Nigerian, says that in his part of the world, that sort of thing is strictly for the hicks in the stix — “straight down from the trees, as you might say.” This strikes me as wrong. I have no problem with the character being a snob, or disgusted with what he sees as superstition, but I have trouble believing that a black man would express his contempt in such stereotypically white racist terms.

Later on, it’s heavily implied that a sadistic Haitian slave owner, backed up by a corrupted voudoun god, helped to touch off the revolution in Haiti. I am not comfortable with that. I think Rohan intended to blame the brutality of the revolution on his villain, but this plot point inadvertently suggests that the Haitians might not have overthrown the plantation owners if a white man hadn’t goaded them into it. That strikes me as very wrong indeed.

I should point out that as far as I can tell — I’m not an expert — the voudoun in the story is handled well and respectfully. The gods play a part in the story, and they tend to be a positive force — unless their dark halves are deliberately invoked, which is, of course, one of the menacing possibilities facing the protagonists.

The story is neither mean-spirited nor unfair to its characters; it simply missteps now and then. In short, despite some flaws, I would recommend this book for anyone who’s looking for fantasy on the high seas, or “urban fantasy” that isn’t actually urban, but deals with the slow shading of one world into another.