Pastiches ‘R’ Us: Conan of the Isles

So far in the entries of my informal tour through the Conan pastiches—with a great guest shot from Charles Saunders on Conan the Hero—I’ve focused entirely on the “Tor Era,” the longest and most sustained period of new novels about Robert E. Howard’s Hyborian Age hero. Because of the sheer volume of books in the Tor line, which ran uninterrupted from 1982 to 1997, as well as most readers’ and reviewers’ indifference toward them, the Tor Era provides fertile ground for fresh criticism. It contains a few gems as well among the factory-line production schedule.

So far in the entries of my informal tour through the Conan pastiches—with a great guest shot from Charles Saunders on Conan the Hero—I’ve focused entirely on the “Tor Era,” the longest and most sustained period of new novels about Robert E. Howard’s Hyborian Age hero. Because of the sheer volume of books in the Tor line, which ran uninterrupted from 1982 to 1997, as well as most readers’ and reviewers’ indifference toward them, the Tor Era provides fertile ground for fresh criticism. It contains a few gems as well among the factory-line production schedule.

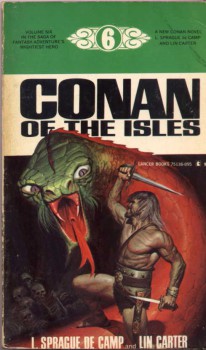

But I’ve neglected the earlier Conan pastiches, from publishers Lancer (Sphere in the U.K., later Ace in the U.S.) and Ballantine. Before Tor started its Conan factory with Robert Jordan’s Conan the Invincible, the world of Conan pastiches rested mostly in the hands of two men: L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. They filled in a “Conan Saga” that they had imagined through a constructed timeline, and this framework extended into the Tor Era as well, although turning more overstuffed and inconsistent as the books piled up and eventually the whole series put itself to sleep and Howard burst back into print.

One of the results of de Camp and Carter’s addenda to Conan’s history is the odd, uncharacteristic, yet hypnotically entertaining Conan of the Isles. Years ago I wrote a detailed review of this 1968 novel for a forum posting. I’ve pulled up that old review and done some dusting, revising, and re-thinking to present the first “Pastiches ‘R’ Us” installment that examines the controversial First Responders of the neo-Conan world.

De Camp and Carter weren’t the only authors in the Lancer-Ballantine era. In fact, Björn Nyberg wrote the first new Conan adventure to see print, The Return of Conan, although de Camp revised it for publication. Other contributors to the Ballantine series came from Andrew J. Offut, Poul Anderson, and Karl Edward Wagner, whose Conan: The Road of Kings, is the finest Conan story I’ve read outside of Bob Howard’s typewriter.

But it was the unusual pairing of science-fiction author L. Sprague de Camp with feisty fantasy fan and historian Lin Carter that cemented the tradition of creating new stories for Conan of Cimmeria. De Camp and Carter started working at Conan pastiches with “fill-in” short stories designed to bridge perceived gaps in the chronology of Howard’s stories and weave them into a complete saga of Conan’s life. Eventually, they started to write full novels to stitch together their story, starting with Conan of the Isles.

As de Camp and Carter envisioned their saga, Conan of the Isles is the conclusion. It represents the terminal point in the character’s career. The writers based the story on vague hints that Howard left in a letter about Conan exploring western islands, but then they fly off into some strange speculative fiction territory to create what must count as the weirdest of all Conan pastiche novels. It also contains some of the most unabashed sword-and-sorcery fun that the two men wrote in the series. It sometimes reads as if it were a treatment for a comic book that famed artist Jack Kirby would illustrate.

I am fast in the position that the only “true” Conan appears in Howard’s writing, and that any “saga” of the character can be best appreciated through reading the stories in the order that Howard wrote them—Crom blast these chronologies! However, I also have a flexible position about the pastiches. These books are imitations, but that doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy Conan-imitations from skilled writers. I still find Conan of the Isles an immense science-fantasy high, even if it doesn’t feel like it could exist in the same continent with Howard’s Cimmerian warrior. Since the new writers sent Conan out from the Hyborian Lands to find the remnants of a lost continent, they might also have been aware of how far off their fantasy creation was from the character who appeared in Weird Tales.

Although the veteran writers conjure up a breezy fantasy adventure with a pulpy sense of excitement, Conan of the Isles will put to the test a reader’s taste in post-Howard Conan. Which is more important: adherence to Howard’s spirit, or wild adventure? If you can have both, that’s wonderful. But I think most of us would prefer to have a good sword-and-sorcery adventure instead a boring and slavish attempt to imitate Howard. You will never mistake Conan of the Isles for Howardian Conan, but you won’t mistake it for a boring novel either.

As the action begins, Conan has ruled Aquilonia for over twenty years and now nears his mid-sixties. After the death of Queen Zenobia in childbirth, Conan wearies of ruling the great kingdom. A sudden attack of mysterious “Red Shadows” spirits away Count Trocero and many other people of Aquilonia. In a dream, Conan sees the prophet Epemitreus, who tells him he must cross the Western Ocean to stop the evil of the Red Shadows. The Prophet gives Conan a phoenix-shaped talisman to aid him. Conan abdicates in favor of his twenty-year-old son Conn (a de Camp and Carter invention who would play a major part in their 1977 episodic novel Conan of Aquilonia) and secretly heads to the west on his last adventure.

As the action begins, Conan has ruled Aquilonia for over twenty years and now nears his mid-sixties. After the death of Queen Zenobia in childbirth, Conan wearies of ruling the great kingdom. A sudden attack of mysterious “Red Shadows” spirits away Count Trocero and many other people of Aquilonia. In a dream, Conan sees the prophet Epemitreus, who tells him he must cross the Western Ocean to stop the evil of the Red Shadows. The Prophet gives Conan a phoenix-shaped talisman to aid him. Conan abdicates in favor of his twenty-year-old son Conn (a de Camp and Carter invention who would play a major part in their 1977 episodic novel Conan of Aquilonia) and secretly heads to the west on his last adventure.

In the Argossean port of Messantia, Conan meets an old companion from his days with the Brachan pirates, Sigurd of Vanaheim. King Ariosto of Argos, who has also suffered from the Red Shadows, approaches Conan in a tavern to offer to fund his voyage over the Western Ocean. Conan, under his old guise of Amra the Lion, picks a tough crew and sails with Sigurd on the ship the Red Lion. What they find out in the Western Ocean will put them face-to-face with the last remnants of sunken Atlantis, Demons from the Darkness, and a city filled with sacrifice, dragons, and evil labyrinths.

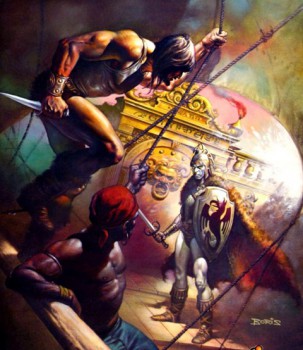

As this bare-bones outline makes clear, the plot of Conan of the Isles barely pauses to take a breath. Like a movie serial or an Edgar Rice Burroughs adventure, this is “One Damn Thing After Another.” Where a Tor novel would develop a story around different character subplots, interactions, and conspiracies, Conan of the Isles just points Conan in a direction and sends him on his gory way. The novel flies along a linear path: monster, fight, escape, rescue, monster, sorcerer, duel, escape, rescue, etc. Imaginative weirdness appears throughout. Character drama takes a back seat—the only supporting characters are Sigurd and Metemphoc the master thief—and action hurtles nonstop across the page.

Thankfully, most of the action clicks. Conan’s horrific contest against the horde of huge rats ranks as one of the best-written suspense sequences in a pastiche novel. In fact, this is one of the only scenes in a non-Howard Conan work that stands out for me as truly memorable. The navel battle scenes are also exciting, and plenty of giant monsters show up to threaten our aging hero. (I adore big monsters, so the book earns extra points with me for throwing them in.) The finale is just what you want from a fantasy adventure: constant action, monsters, magic, horror, and ironic turnabout.

Where Conan of the Isles deviates most from Howard’s world is in its pseudo-scientific gadgetry and the outlandish culture of Antillia. Howard made the Hyborian Age realistic, injecting historical cultures into a hodgepodge fantasy setting and adding doses of supernaturalism. De Camp and Carter, however, toss Conan into lands beyond knowledge, and all convention collapses into a science-fantasy parade of peculiarity. The Antillians sail impractical dragon boats, use “super metals” like orichalcum, wear breathing helmets, don glass armor, hurl stun-gas grenades, and wield crystal swords. Their culture has hints of meso-American Indians (a de Camp touch, based on the pseudo-scientific nineteenth-century bestseller Atlantis: The Antediluvian World by Ignatius Donnelly, who theorized an Atlantean origin for Central and South American empires), but otherwise the Antillians might have leaped out of one of Burroughs’s Barsoom novels.

This strange detour of style from Howard’s Hyborian Age draws comparison with the later Steve Perry novels. Perry has gotten heavy—deserved, I believe—for his loose high fantasy approach to Conan, which feels more at home in a Star Wars novel or a D&D tie-in. (See my review of Conan the Free Lance for more thoughts about this.) De Camp and Carter diverge into this “anything goes” territory as well, but there’s a significant difference. Perry’s vision is distinctly a post-Howard and post-Tolkien one. It’s the fantasy era of David Eddings, Robert Jordan’s “Wheel of Time,” and Terry Brooks. De Camp and Carter, however, go backwards from Howard and into Edgar Rice Burroughs and A. Merritt for their inspiration in Conan of the Isles. They stay within a pulp tradition; not the same one as Howard, but nonetheless it’s a divergence with an organic familiarity for a reader that Perry’s work lacks.

The personal interests of the authors are on the frontlines; more than any other Conan piece they authored, Conan of the Isles belongs to de Camp and Carter. Carter brings the pulpy delirium and the nonstop rush of insane events. De Camp provides a fascination with the Atlantis legend and the origins of myths in general, as well as his “logical fantasy” approach to mythic events. He even suggests that Conan will become the basis for the Aztec myth of Quetzalcoatl, “the Feathered Serpent” who sailed out of the west to their lands.

The novel presents the an elderly version of Conan, and de Camp and Carter do admirable work with this aged character. They pile on reminders of the past, which gives a sense of closure for the final story of Conan’s career (at least in de Camp’s chronology). There’s also an effective moment of reflection for the hero: “Now that [Zenobia] was gone, he found himself often thinking of her, in moods of black depression that were unlike him. While she lived, he had taken her devotion as his due and thought little of it, as is the way of the barbarian. Now he regretted the words he had not said to her and the favors he had not done for her.” Conan has matured; facing the approach of the “Long Night” of death gives him a sense of regret and loss appropriate for someone his age. Howard himself might have approved of this touch of reflective darkness.

If readers can get past the non-Howard world of Conan of the Isles, they’ll find the novel’s biggest flaw is its authors’ predilection for overstuffing their prose. This is especially noticeable in the dialogue: Conan is overly chatty, and Sigurd shouts too many “salty dog” speeches. Here’s a good example of the often heavy-handed writing: “The northman grinned broadly and gave a bellow of joy that would have summoned a hippogriff in the mating season had one been within earshot.” A hippogriff is an unlikely Hyborian animal. (One of the authors must have had Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso in mind, since they use both the name “Ariosto” and Ariosto’s invention, the hippogriff.) In places, their word choice falls flat or else strains too hard to grasp an obscure term. I have never seen anyone use the word “decardiate”—to remove the heart—in a work of fiction before, and I doubt I will see it again. In places the plot moves too fast, and de Camp and Carter rely on coincidences (such as Conan running into Sigurd and Ariosto in the same bar) that seem a bit much.

You can’t expect all of it to makes sense or adhere to traditional Conan, but at least this pastiche lives up to the sword-and-sorcery obligation to entertain with fast, fun, imaginative action. And compared to most of the later Tor novels, Conan of the Isles is fast, fun, and imaginative indeed. It shows Steve Perry that you can make an off-the-wall Conan adventure keep the reader engrossed instead of distracted.

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning science-fiction and fantasy author. He received the Writers of the Future Award in 2011 for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and has two stories forthcoming in Black Gate and a number of ebooks on the way. He also knows Godzilla personally. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com, and follow him on Twitter.

Thanks, Ryan. Another great review of the pastiches. Keep ’em coming!

I read the entire 12-book run of the Lancers as a teen in the early 80’s. I had read them in response to being introduced to Conan through Milius’ movie (which, despite it’s flaws as a pastiche, is still among my top 5 favorite movies). I remember when I was reading them that my brain didn’t really register the differences between the Howard originals and the pastiche fillers and add-ons. Of course, that may have been due to de Camp’s heavy-handed editing of Howard’s original stories.

All that being said, I still recall Conan of the Isles being one of my favorite book-length Conan stories (second only to Conqueror). You are pretty spot on with this review, and now I almost want to break out my copy and give it another go.

[…] because I can’t resist, here’s Ryan on L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter’s Conan of the Isles (Lancer, […]