The Real “Twilight”: John W. Campbell’s

I’ve discovered that once you start writing about 1930s magazine science fiction — a field small enough for thorough analysis, but bursting with enough wonders to fill the galaxy — it becomes difficult to stop. Pondering the marvels of Stanley G. Weinbaum’s 1935 classic “Parasite Planet” urged me to sift through my pile of Del Rey “Best of…” paperbacks, which are crammed with the stories that helped me reach a kind of SF maturation when I was a young reader.

I’ve discovered that once you start writing about 1930s magazine science fiction — a field small enough for thorough analysis, but bursting with enough wonders to fill the galaxy — it becomes difficult to stop. Pondering the marvels of Stanley G. Weinbaum’s 1935 classic “Parasite Planet” urged me to sift through my pile of Del Rey “Best of…” paperbacks, which are crammed with the stories that helped me reach a kind of SF maturation when I was a young reader.

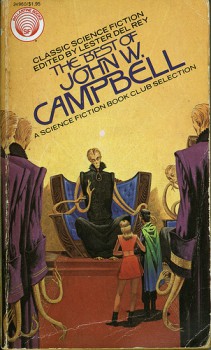

The first of the Del Rey anthologies I purchased, long enough ago that it was new and sitting on the shelf of a chain bookstore, was The Best of John W. Campbell. The reason I bought this title was simple: it contained “Who Goes There?”, the basis for two movies I loved, The Thing from Another World (1951) and The Thing (1982). I already knew Campbell’s reputation as an editor, but hadn’t experienced his earlier career as two different authors, John W. Campbell and Don A. Stuart.

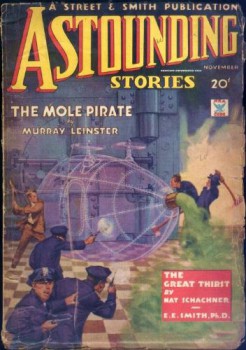

If Stanley G. Weinbaum was “a Campbell author before Campbell,” so too was Campbell — or at least, Don A. Stuart was. The proof is in “Twilight,” a story under the Stuart name that appeared in the November 1934 issue of Astounding Stories during the tenure of editor F. Orlin Tremaine. I may have bought The Best of John W. Campbell for “Who Goes There?,” but it was “Twilight” that entranced me and became one of my favorite short stories of any genre.

(And yes, as the heading of this post indicates, to me the title “Twilight” always means this story. It had too potent an effect on me to ever allow anything else, no matter how much popular culture it devours, to steal the word “twilight” for other use.)

Tremaine’s Astounding sits in the shadow of what Campbell would do with the magazine when he took over in 1937 and changed it to Astounding Science Fiction. But I believe that what Tremaine did with the magazine was remarkable in its own way. He pulled the title from its lagging position in the science-fiction markets, behind Wonder Stories and Amazing Stories, and made it the pack leader. The magazine increased in size from 144 to 160 pages, got the best artwork placed on the cover, paid its authors better rates in a timely fashion, and pushed the boundaries of science fiction with what Tremaine called “Thought Variant” stories. In simple terms, these were stories that avoided clichés or reversed them, and challenged readers with bold ideas that made them look at the world on the printed page in a different way. Without the build of success from Tremaine’s Astounding Stories, there never could have been a John W. Campbell Astounding Science Fiction.

Campbell the writer was part of this early success. Under his real name, Campbell had sold science-fiction stories since 1930. His first, “When the Atoms Failed,” appeared in Amazing Stories in January of that year. (Only one of these early stories, “The Last Evolution,” appears in The Best of John W. Campbell, and I must admit that I don’t care for it much.) These were “super-science” tales in the mode of E. E. Smith’s wild adventures that were the dominant model of the time. But Campbell wearied of the style, and used a slant on his wife’s maiden name to create the Don A. Stuart pseudonym to try something a bit different. “Twilight” was the result, and it fits the mold of a Thought Variant story that Tremaine and his readers were looking for. Isaac Asimov remembers reading “Twilight” at the time it was published and not liking it — or any of the other Stuart stories. “I found them too quiet, too downbeat, too moving. I wanted action and adventure, and I was simply incapable of following Campbell up to the Stuart level. I eventually did, but it took a few years. I was not as good a man as Campbell was.”

“Twilight” remains remarkable today for its emotional portrait of a dying race. It also takes some strange narrative risks, not all of which succeed, but which stand out nonetheless. What makes it so different from the “super-science stories” of the 1930s is that, well, not much really happens in it. “Twilight” is close to plotless. It consists of a man telling a story about a man telling a story about a tour of a future Earth where the race has slipped almost into oblivion. Little in the way of “events” occur, and only in the final pages does Campbell hint about a change that might come about from the main character’s action. Essentially, “Twilight” is a walkthrough, distilled through two narrators.

“Twilight” remains remarkable today for its emotional portrait of a dying race. It also takes some strange narrative risks, not all of which succeed, but which stand out nonetheless. What makes it so different from the “super-science stories” of the 1930s is that, well, not much really happens in it. “Twilight” is close to plotless. It consists of a man telling a story about a man telling a story about a tour of a future Earth where the race has slipped almost into oblivion. Little in the way of “events” occur, and only in the final pages does Campbell hint about a change that might come about from the main character’s action. Essentially, “Twilight” is a walkthrough, distilled through two narrators.

The double narration device is the trickiest aspect of the story for readers today, and I think Campbell handles it a bit clumsily. As the story opens, a real estate agent named Jim Bendell is speaking casually to an unnamed first-person narrator. The dialogue is friendly, contemporary. Then Bendell talks about a bizarre man he picked up on the road the previous day. The style shifts, the quotation marks vanish, and Bendell becomes the narrator. He converses with the strange man, who claims he is a time-traveler from a thousand years in the future who traveled seven million years forward, and when trying to get back to his own time overshot it and landed in 1934.

And then, another shift. The quotation marks again vanish, and the time-traveler, Ares Sen Kenlin, becomes the narrator. This is where “Twilight” really begins; the colloquial voice disappears and Campbell plunges the reader into an exploration of the destiny of the human race — a lonely one where curiosity and wonder have died, and machines that should have been turned off long ago continue their tasks across the planet and the solar system.

Every time I’ve read “Twilight,” I find myself having to coast over the bumps of these two early narrator shifts. A double-imbedded story requires extra attention from the reader, but it’s only necessary to get to the meat of the story, the dream-like marvel of the final sunset of humanity. Campbell at one point leaps back from Kenlin’s voice for Bendell to make a crack about real estate, which is a weird distraction, but otherwise the prose holds a slow and hypnotic spell once it starts its tour of seven million years into a sorrowful and fading future.

Campbell achieves remarkable effectiveness with music, a difficult trick in the silence of prose. The song of the dying race becomes a theme that the reader can “hear” throughout the story:

He sang the song. Then he didn’t have to tell me about the people. I knew them. I could hear their voices, in the queer, crackling, un-English words. I could read their bewildered longings. It was a minor key, I think. It called, it called and asked, and hunted hopelessly. And over it all the steady rumble and whine of the unknown, forgotten machines.

The machines that couldn’t stop, because they had been started, and the little men had forgotten how to stop them, or even what they were for, looking at them and listening—and wondering. They couldn’t read or write any more, and the language had changed, you see, so that the phonic records of their ancestors meant nothing to them.

But that song went on, and they wondered. And they looked out across space and they saw the warm, friendly stars—too far away. Nine planets they knew and inhabited. And locked by infinite distance, they couldn’t see another race, a new life.

Campbell keeps this crepuscular tone sustained until the end (the minor real-estate pothole excepted) and it’s an incredible performance… especially for 1934. The same issue in which “Twilight” first appeared was also running the fourth installment of E. E. Smith’s The Skylark of Valeron, zip-pow super-science if there ever was one. I love E. E. Smith, no apologizes, but “Twilight” couldn’t have been more different from a “Skylark” adventure, and readers noticed it — and loved it.

John W. Campbell’s impact on science fiction is inarguable, although you might debate that it amounted to a monopoly that required a second revolution two decades later in the genre. I sometimes wonder if I prefer Campbell as a writer or an editor. Perhaps my opinion doesn’t matter either way, since he did become an editor and thus made me capable of even asking the question. It’s possible that, the same way Stanley G. Weinbaum might have led a revolution simply as a writer had he lived, that Campbell could have achieved something similar just with the example of works like “Who Goes There?” and “Twilight.” Only the dimensional travelers and their thought-variant stories can ever answer these questions.

And please, annoy the people around you: Whenever anybody mention Twilight, always say, “Oh, I love John W. Campbell! Which do you think is a better version of ‘Who Goes There?’: the Howard Hawks or the John Carpenter?” Wait patiently for a reply.

Man, I need to read more Campbell. Great, great article Ryan.

Reminds me just how instrumental the Del Rey “Best of…” books were in educating me about the best SF writers in the field, too. And that some of their finest work could be found at short length.

Maybe I’m just being a cranky old man again, but it seems like there’s little doing the same these days. The money in publishing is in novels, and that’s where all the focus is.

John

[…] someone already wrote about it: Ryan Harvey over at Black Gate, a fantastical fiction blog. Read the article here. Says Harvey: And yes, as the heading of this post indicates, to me the title “Twilight” always […]

[…] Campbell wrote 18 stories under the Don A. Stuart name, beginning with “Twilight” in the November 1934 issue of Astounding. “Twilight” is one of the most famous Stuart tales, and indeed one of the most critically acclaimed SF stories of the pulp era. Here’s our own Ryan Harvey, in his Black Gate article “The Real Twilight“: […]

Where I live (South Africa), you’ll never see an old pulp magazine, so anthologies are my only gateway to the magazine fiction of yore.

So I discovered both “Twilight” and “Who Goes There?” in the Damon Knight anthologies Beyond Tomorrow and Toward Infinity. They became favorite stories, and I was delighted to find them both in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology series a few years later.

For decades after that, I was hoping to find other Campbell/Stuart stories in the same vein, but I wasn’t impressed with the other two I read (“Forgetfulness” and “Cloak of Aesir”). I was beginning to think my two old favorites were the only Campbell stories I’d ever like, when I finally got around to “Night”, which is in a similar vein to “Twilight”, and which I also loved.

I have several other Campbell stories somewhere in anthologies, including “The Brain Stealers of Mars”, but I’m not sure whether there’s any more real treasure to be found …

Incidentally, I agree with Ryan. For me, “Twilight” will always be a story from a tattered old pulp magazine in someone’s attic, and from several of my favorite books.