Frederick Faust, Bound for SF and The Smoking Land

The Smoking Land

The Smoking Land

Frederick Faust writing as George Challis (Argosy, 1937)

I’m returning to the subject of Frederick Faust for the third time this year. But I have a specific, Black Gate-centered justification for it: I wish to unearth his single novel of science fiction, a piece of Lost World and Weird Science strangeness called The Smoking Land.

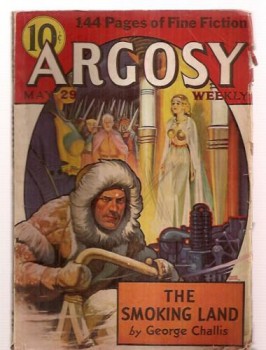

Faust, under Max Brand and his eighteen other pseudonyms, made his reputation with Westerns, but he did write in almost every genre that appeared in the story magazines of the time. He penned historical adventures, detective tales, mainstream short stories for the “slicks,” and espionage yarns. In 1937, he authored his one true science-fiction work, the novel The Smoking Land, which appeared serially under the pseudonym George Challis in the old warhorse of the pulp world, Argosy, starting in the May 29 issue.

(In fact, this Saturday evening I stood face-to-face with one of the actual issues of Argosy in which the novel was serialized, housed in the pulp collection at Author Services in Hollywood. Actual surviving issues of the self-destructive pulps are rare finds, and they need special protection to survive. And hey look! One of the Argosy installments of The Smoking Land shares space with the Cornell Woolrich story “Clever, These Americans”! . . . Okay, so maybe only I care.)

In the introduction to a 1980 small press edition of The Smoking Land, Robert Easton, Faust’s biographer and son-in-law, speculated on this sudden turn in the writer’s career:

Why did Faust write Smoking Land, his only work of science fiction cum adventure? Why did a master of so many profitable genres turn to one untried? Nobody knows but I have an idea. He had returned after long residence aboard to find this country emerging from economic depression, astir with new possibilities. The flights of Lindbergh, Earhart, and Byrd were big news. Speculation as to future voyages into space in vehicles traveling at incredible speeds was rife, not to mention death rays, atom smashes, and jet propulsion. He sat down at his typewriter because a new idea challenged him. It would test his capacity and that of his readers for enlarged experience, and it might make an old pro a few dollars on a new course which, if mastered, would enhance his self image.

Possible, yes. But I think Easton’s last point makes the most sense overall. The simple reason of economics probably drove Faust into SF’s cybernetic metal arms. Faust, through the 1920s, had a steady market with Western Story Magazine, where he received the handsome rate of 5¢ a word for his work. But the reality of the Great Depression forced many magazines to cut down their word rates, and although Faust held out against the pay-decrease for a few years, it finally struck him at Western Story. He almost completely abandoned the magazine and sought other lucrative markets, which also meant casting wide his genre net. To experiment with the burgeoning of science-fiction mags, which were on the verge of John Campbell taking over Astounding Stories, and trying out an SF adventure must have seemed an obvious direction for Faust. And Argosy, a general interest pulp (indeed, the first pulp magazine) was a natural home for whatever he tried. The magazine had purchased Faust’s first pulp stories in 1917, and serialized one of his classic novels, The Untamed.

The Smoking Land opens as if it were a Western, and this semi-frontier attitude will continue even as the novel eventually turns into a Lost World story. The hero and first-person narrator comes right from the badlands with a toughened Westerner’s skepticism. He’s Bill Cassidy, “Smoky Bill,” of the Bitterroot range Cassidys, who are liars and sometimes scoundrels, “but good men to ride with.”

The Smoking Land opens as if it were a Western, and this semi-frontier attitude will continue even as the novel eventually turns into a Lost World story. The hero and first-person narrator comes right from the badlands with a toughened Westerner’s skepticism. He’s Bill Cassidy, “Smoky Bill,” of the Bitterroot range Cassidys, who are liars and sometimes scoundrels, “but good men to ride with.”

Smoky Cassidy is sitting outside his shack watching the sunset one day when up rides Dr. Herbert Franklin, a mathematician. He needs Cassidy’s help to protect Dr. Cleveland “Cleve” Darrell, an atomic physicist who has long been Cassidy’s close hunting and fishing friend. Dr. Darrell is working on a project that has made him many foes, and Dr. Franklin believes that if he doesn’t get the proper protection tonight in his lab, he won’t last to the next sunrise. That’s all the prompting that Cassidy needs (and he certainly doesn’t want the mathematician to explain all that confusing scienc-y stuff to him just yet) and he leaps on his horse to ride out to his close friend’s laboratory under a mountain.

Cleve Darrell can’t at first explain properly to Cassidy what he’s working on in his sealed laboratory, and he doesn’t get a chance to later on. A moment of treachery ensues, and something goes wrong: the whole mountain explodes, supposedly taking Darrell with it. Cassidy makes a miraculous survival. And that should be that.

But in British Columbia, a tourist discovers a piece of utterly unknown material with these strange words written on it: “Bound north of Alaska for the Smoking Land and…” Cassidy recognizes the handwriting as Cleve Darrell’s. With only this clue, Cassidy heads north toward the Arctic to find if anyone has heard of this mysterious “Smoking Land.”

After a period of no luck, Cassidy at last come across a man who recognizes the phrase “Smoking Land.” Cassidy almost gets killed for mentioning it, but in the struggle it’s the weird man who ends up dead. The only hint that Cassidy has that he came from the Smoking Land is the bizarre cuirass on the corpse, made from the same unknown material as the cryptic shard with Darrell’s handwriting.

This section of the book feels like Faust embracing Jack London’s northern adventure tales, which inspired a number of his Westerns, such as Sixteen in Nome. The hero even befriends a wild, giant white dog in his icy travels, whom he names “Murder.” (Faust was a devoted dog lover, and canine companions appear in other of his stories and are sometimes the main characters, as in the wonderful animal fantasy The White Wolf.)

After an eight-month trudge through the Arctic, Cassidy at last reaches the Smoking Land: an island with a great active volcano at its center. Cassidy and Murder soon run into the inhabitants, and Faust grandly introduces us to his admiration for William Shakespeare.

The people of the Smoking Land are the remains of a Northwest Passage attempt forever frozen in their original Elizabethan English society, complete with the language style, but also with dashes of advanced technology they have developed during their years of isolation. They worship the goddess of the volcano and follow the rules of an inner circle of Wise Men. When Cassidy accidentally makes their priestess Sylvia violate an oath not to enter a sacred chamber in the volcano, she and he receive death sentences. Cassidy does have a hope, for Cleve Darrell is also a resident of the Smoking Land. How he got there is whole other story of super-science, and Cassidy learns that his old friend Cleve might no longer be a friend.

No one will confuse The Smoking Land with hard SF. Smoky Cassidy isn’t much for science, either hard or soft, and he’s always asking that others in the story put off explaining the scientific marvels to him, since he wouldn’t understand them. What Faust does provide is sketchy “super weapon” fuzzies with more than a touch of Nicola Tesla. A few don’t make much sense at all: the unknown and impervious material is explained a kind of “vegetable weave.”

No one will confuse The Smoking Land with hard SF. Smoky Cassidy isn’t much for science, either hard or soft, and he’s always asking that others in the story put off explaining the scientific marvels to him, since he wouldn’t understand them. What Faust does provide is sketchy “super weapon” fuzzies with more than a touch of Nicola Tesla. A few don’t make much sense at all: the unknown and impervious material is explained a kind of “vegetable weave.”

Faust keeps the scientific wonders confined to the opening and the last quarter of the novel, while the middle is romantic adventure within a lost civilization. It’s a crazy lost civilization as well, since the technology doesn’t gel well with its many English Renaissance elements. There’s also a loss of the exotic when the people of your lost civilization have names likes Arthur, Ralph, Alice, and Wilbur.

There is plenty of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jack London (who also wrote accomplished science fiction along with his Yukon tales), and even a smidgen of E. E. Smith in The Smoking Land. But I’ll wager that the author who influenced Faust the most in writing The Smoking Land — aside from Shakespeare, of course — was A. Merritt. At the time, in the era before the famous “Golden Age” of magazine science fiction started, Merritt’s fantastic scientific romances had made him the most popular writer in the genre. His stories of hard-as-nails adventurers who undertake journeys to majestic lost civilizations and encounters with fierce priests and unforgiving religions in the farthest reaches of the Earth match exactly the plot that Faust uses in The Smoking Land.

But Faust’s style is leagues away from the grandiose arabesques of Merritt. Faust was much more a pure storyteller than Merritt, and he had a distinctive and friendly voice from his years as a frontier wordsmith. The Smoking Land features many interruptions of colloquialisms from its narrator even in the middle of fantasy terror: “And then Fate, or whatever you choose to call it, stepped in and batted out a homerun for me, in the ninth inning, with the score one to nothing against me.”

There is much to recommend The Smoking Land to pulp readers: it moves fast and contains the usual number of surprising character twists that make Faust’s best work wonderfully unpredictable. But The Smoking Land isn’t among Faust’s best work. It misses the emotional intensity of much of what he did during the 1920s in Western Story Magazine and still achieved in spurts during following decade. Perhaps Faust wasn’t completely comfortable with the SF elements of the story, which might explain why he never wrote another story like it. It might be that in trying to work with the unfamiliar but necessary materials of the genre, he ended up deviating from his powerful characterizations. The Smoking Land is enjoyable — and it’s an important crossroads in pulp history where one of the great genres briefly makes the acquaintance of one of the great authors — but it’s not amazing the way you might hope a “Max Brand Science Fiction Epic!” would be. Compared to his classic Westerns, it’s unmemorable.

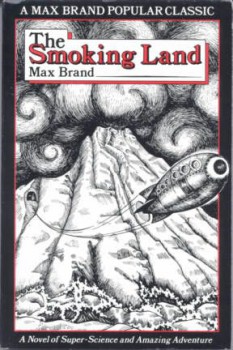

The novel was reprinted in A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine in February 1950 (appropriate, considering how much of Merritt’s common tropes appear in it), and then it did not resurface again until 1980, when Capra Press released a facsimile edition of the original Argosy run. Faust’s byline was changed to “Max Brand,” now a trademark, and the subtitle “A Novel of Super-Science and Amazing Adventure” was appended. Faust’s son-in-law, Robert Easton, provided the brief introduction. Unfortunately, The Smoking Land has seen no further reprints since then. It’s something the Paizo Publications’ “Planet Stories” line should consider picking up.

Ryan–on your recommendation I recently started reading Max Brand’s THE LEGEND OF THUNDER MOON. It’s fanTAStic! The prose flows like music and the Cheyenne world is fascinating. I’m only a few chapters in but I’m severely digging it.

I would LOVE to read this! Thanks once again for a marvelous post Ryan. Now I’m going to have to kick your a** you know; I don’t have very much time for personal reading these days 😉

John: Glad you like The Legend of Thunder Moon so far. Almost anything Faust wrote during that period is worth reading, but the Thunder Moon novels are something special.

Jason: Well, rather get my butt kicked than not tell people about a Faust SF novel! 🙂

Merritt and Faust had something of a mutual admiration society going. They began collaborating on a novel, but it fell apart before progressing far. I would say THE SMOKING LAND is Faust getting his urge to write a Merritesque tale out of his system.