Looking Back on the first Sword and Sorceress

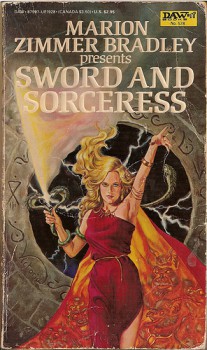

Sword and Sorceress I

Sword and Sorceress I

Edited by Marion Zimmer Bradley (DAW, 1984)

The late author and editor Marion Zimmer Bradley probably could not have dared to guess in 1984 that her anthology series, Sword and Sorceress, would turn into a yearly and best-selling institution of fantasy short stories that would extend past her death. That the first volume in the series bears a Roman numeral shows that she did believe the anthology would see at least two volumes; that it now reaches into the mid-twenties (with the twenty-fifth due this year) shows just how much sword-and-sorcery has embraced inclusiveness during the last three decades. Strong female heroines are now a key part of the genre, completing what C. L. Moore started with her amazing — especially for the time — Jirel of Joiry stories of the 1930s. Bradley invokes Moore a few times in her introduction, and the book is dedicated to both Moore and Jirel.

Over a quarter of a century after publication, the first Sword and Sorceress holds up quite well, while still showing some of the growing pains of sword-and-sorcery in the 1980s. Reading through it makes it clear that the sword-and-sorcery revival still had a distance to go in 1984. About three quarters of the stories Sword and Sorceress I are good-to-excellent, but like all anthologies it has rough patches, some shaky editorial picks, and a few pieces that don’t hit at all. As the series had just started, Bradley did not have a large pool of submissions to pick from. Later volumes would improve the mix as the number of works submitted increased, but this is the start, and therefore worth reading for its historical importance, saggy spots and all.

It’s quite impressive how many of the writers presented here have remained active and successful in speculative fiction. Authors in the Table of Contents who have made themselves major names in the field include Charles De Lint, Jennifer Roberson, Phyllis Ann Kar, Emma Bull, and Robin Wayne Bailey, who served as the president of the SFWA. And it’s no fluke that two of the best stories in Sword and Sorceress I come from Glenn Cook and Charles Saunders, who continue to have a huge influence specifically on sword-and-sorcery today.

In her introduction, Bradley outlines a few of the story types she didn’t want to see in submissions, but admits that she ended up making exception to each one. Her strongest objection was to “rape and revenge” stories, but she ended up purchasing three, and two of them are the strongest in the whole collection.

The first, “Severed Heads” comes from Glenn Cook, here listed as a “prolific newcomer” (this was before he started his Black Company series that made him one of the hefty sword-and-sorcery revivalists of the 1980s). Set in a semi-classical Arabian world, it follows the girl Narriman who quests to avenge herself on her ravager, a shaghûn who serves entities known as the Masters. The shaghûn has also kidnapped Narriman’s son. The story offers little of the consolations of revenge, adhering to the famous adage about “digging two graves.” The rapist even has the magical power to make his victim enjoy her own violation, which makes the emotional aftershocks triply devastating. There are echoes of C. L. Moore’s “Black God’s Kiss” in the finale, but Cook’s style is his own, and the story is a superlative example of sword-and-sorcery as mature literature.

The second of the rape-and-revenge stories is Diana L. Paxson’s “Sword of Yraine,” which stars her series character Shanna in her origin tale. This is the most graphic of the rape stories, although in this case the rape victim is not the heroine, but her friends. Paxson does not back down from the brutality, and edges close to what might be considered exploitive territory — but I can see why Bradley bought the story anyway. It’s simply too bloody exciting and powerful to turn down and is another highlight of the collection. It’s a very basic tale of bandits looting a shrine and raping the virgins pledged to the shrine’s goddess, and how one of the initiates takes up the sword to defend her sisters. It’s the telling that’s important here; Paxson’s writing is vivid and her final duel is all blood-and-thunder-and-retribution glory. It’s no surprise that she went on to work with Marion Zimmer Bradley on the Avalon series of books. Paxson also edited the first volume of Sword and Sorceress published after Bradley’s death.

The third of the rape stories is less impressive than its siblings. Jennifer Roberson’s “Blood of Sorcery” is simply average. Its main power comes from the world-building, and it has historical interest because it is one of the earliest of her popular “Chronicles of the Cheysuli” about shape-changers. But lacks the driving passion of Paxson and Cook’s pieces.

Before moving on to the rest of the collection, I had better turn to one of the friends of Black Gate, Charles Saunders. “Gimmilie’s Song” is a work of the sword-and-soul subgenre that Saunders helped develop, the African-themed fantasy. Warrior woman Dossouye encounters a strange bela, a “song-teller,” named Gimmilie after a group of bandits attack her. Gimmilie’s tragic story becomes even stranger and more entrancing for Dossouye when she stays in his home and learns of the power he can wield with his music — a gift that has turned into a curse. It’s the standard high quality you expect from Saunders, and the setting makes it stand out from the pseudo-European one of most the other stories.

Sword and Sorceress I opens with a “safe” story about conventional magic and might pitted against an evil magician. “The Garnet and the Glory” by Phyllis Ann Karr uses her series characters, sorceress Frostflower and swordswoman Thorn. The duo meet up with a sorcerer from another world, Dathru, who wishes to possess a magical skill from Frostflower’s world, the manipulation of time. It’s an enjoyable but ordinary story, where an internal magical battle is contrasted against a physical one.

Stephen L. Burns’s “Taking Heart” (his first sale; he has focused principally on science fiction since) has two partnered footpads, Raalt the Thief and Clea the Fox, trying to retrieve the jewel known as the Heart of Arrmik. The male Raalt is the viewpoint character, but Clea is the narrative focus. The story is predictable from early on, but rewarding enough as readers watch as Raalt’s mis-reading of Clea — and women in general — brings him down.

“The Rending Dark” by Emma Bull has a quality I often look for in sword-and-sorcery: a great monster. Bull links her heat-sucking beast into the story of Marya, one of the story’s two female heroines. Marya may see her eventual fate in the distortion of this monster, which was once the son of the innkeeper. The story also dabbles with science-fiction ideas, such as mentioning “mutations,” but these elements are so minor that it seems strange that Marion Zimmer Bradley even felt hesitant for a moment about including this fine piece of work in the anthology.

Charles De Lint has had the greatest continued publishing success of any of the contributors to the first Sword and Sorceress, so contemporary readers might expect something extraordinary from his typewriter. But “The Valley of the Troll” is one of the most straightforward and basic stories in Sword and Sorceress I. A swordswoman and her somewhat inept wizard traveling partner investigate a troll’s lair for treasure and encounter a band of highwaymen. It’s entertaining and a fast read, but for De Lint it’s underwhelming.

It seems that every fantasy anthology is required to include at least one story that jimmies in enough material for a novel into a few densely packed few pages. Most of the time, like in “Gate of the Damned” by the late Janet Fox, this ends up choking off the reader’s involvement. The warrior woman Scorpia is a flat character, and at this point in the anthology this archetype has turned repetitive.

An example of a “novel-within-a-short-story” that does work is “Imperatrix” by Deborah Wheeler (later Deborah J. Ross). This is one the best works here, although the surprise ending isn’t that much of a surprise. The narrator is a man, Eddard, but the hero is Charlla, a warrior whose services Eddard purchases for his master Bardon for a journey to the sanctuary Har Yndion. Charlla has a goal, one much greater than that of a mercenary, as Eddard begins to discover during their travels. Although a short story, Wheeler packs it with the action of an epic turning of the tide for a people.

“With Three Lean Hounds” by Pat Murphy presents one of the most fairy-tale tinged of the offerings, with elements of a complex mythology. The heroine is a young thief who comes to believe that she is the daughter of the Lady of the Wind, and she joins a minstrel on his way to the Lady. The minstrel has his own secret and his own goal in meeting the lady. Aside from a fine quest-journey story, Murphy also includes a giant, a dragon, and an undine, making for a nice short feast of high fantasy.

Anodea Judith’s “The House in the Forest” is one of the shortest pieces, and one of the weakest. It’s a primarily internalized adventure about a healer, and is the sort of stream-of-consciousness fantasy that does absolutely nothing for me.

The story with the most humor, “Daton and the Dead Things,” thankfully doesn’t spill over into outright comic fantasy. Author Michael Ward keeps the quirk in the voice of his heroine, who takes a raised eyebrow and smirk approach to her adventure seeking out a former partner who stole from her. The quest puts her in the clutch of the cyclopean creature Daton and his collection of prisoners who are pretending they are the living dead so Daton won’t eat them. It’s a lark of black comedy.

Only two of the stories are historical fantasy, and both are set during Roman history. “Child of Orcus” by Robin W. Bailey takes place a month after the death of Caligula and features Diana, a former female gladiator (Bradley’s notes point out that the mad Emperor did use gladiatrix in the arena), who does work-for-hire for Empress Messalina. Diana’s employer sends her to investigate a Death Cult following the god Orcus in the mountains, hoping to obtain their secret for immortality. The story, from its realistic historic backdrop, plunges into dark supernatural territory with a meeting with Orcus himself. The only flaw in this otherwise excellent story is a standard wager-by-duel finale that we’ve seen in too many sword-and-sorcery yarns.

The other historical piece, set in the earliest days of Rome’s conquest of the Italian Peninsula, closes out the collection. “Things Come in Threes” by Dorothy J. Heydt is the shortest piece in Sword and Sorceress, and although Bradley felt it was the best way close to the collection, it doesn’t leave much impression. The infernal “Child of Orcus” would have been a better end.

After a gap of a few years, Sword and Sorceress lives on under the editorship of Elisabeth Waters. The reading period for the newest book, Volume XXV, closed in May.

“…but like all anthologies it has rough patches, some shaky editorial picks, and a few pieces that don’t hit at all…”

Ahem. All?