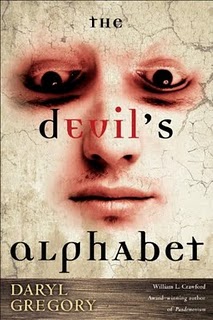

The ABC’s of DNA and Other Thorny Themes: Daryl Gregory’s “The Devil’s Alphabet”

Paxton Martin has come home to Switchcreek, Tennessee, to attend the funeral of a childhood friend. He drove in from Chicago, pulling an all-nighter, because he could not decide until the last minute if he wanted to go back. He’d been living in Chicago since running away from Switchcreek, 13 years ago, after everything changed.

Paxton Martin has come home to Switchcreek, Tennessee, to attend the funeral of a childhood friend. He drove in from Chicago, pulling an all-nighter, because he could not decide until the last minute if he wanted to go back. He’d been living in Chicago since running away from Switchcreek, 13 years ago, after everything changed.

The opening of any number of novels, classic in its prodigal simplicity, promising Faulknerian brambles with a dash of Wolf (Thomas that is) and a thread of O’Connor. The returning son of the local preacher, reconnecting, abrading old scabs, stirring nearly-dead ashes, the stuff of Americana along gothic lines. The changes, of course, mask how much everything has remained pretty much the same. After a time, one can even overlook those changes…

Not in Daryl Gregory’s second novel, The Devil’s Alphabet. The changes in this case cannot be ignored. By anyone.

Switchcreek has undergone a profound experience in the form of mutations which swept through the small population, transforming many residents into distinctly divergent species. The genetic instructions for these people have been rewritten by some unknown process, which did not strike all people. When the changes worked their way through, Switchcreek was home to populations of what became known as Argos, Betas, and Charlies, as well as the untouched population.

Pax’s own parents changed. His mother did not survive, but his father, Reverend Harlan Martin, did, becoming a Charlie, a massive, bulging block of a man, his weight pushing up toward five hundred pounds.

The betas are almost otter-like in appearance, though hairless, and as it emerges, all females, reproducing parthenogenetically.

The Argos are giants, hard-surfaced, immensely strong, distorted frames, the women larger and stronger than the men.

Pax’s two best friends, Deke and Jo Lynn, underwent the changes, Deke becoming an argo, Jo Lynn a beta. It is Jo Lynn’s funeral that brings Pax — who escaped the changes — back.

Pax himself, however, sometimes wonders if there is not a fourth vector, one that still maintains the appearance of a “normal” human, but inside is utterly different. He feels himself to be one of these, but he has no proof other than his sense of isolation, his inability to connect with other people, his indifference to the world around him. Returning to Switchcreek offers him a chance to find out.

Jo Lynn supposedly committed suicide. Deke is not so sure. Nor, frankly, is Pax, who has a hard time imagining Jo Lynn ever becoming so despairing that such an end might seem the only way. But Pax is no detective and Deke, while in many ways the town sheriff, has no official standing with state law enforcement. Nevertheless, there is a missing laptop, questions about fertility, and something that looks very much like drug trafficking going on in this community Pax once called home, and Pax’s own troubled relationship with his aging and ill father drag him into the mire of Switchcreek.

In some ways, the story is reminiscent of John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos but Gregory has more of the tools at his disposal, both scientifically and philosophically, at work. The entire history of defining humans and races and what counts politically depending on which conclusions hovers in the background throughout the novel. He never quite brings these issues to center stage, and for that he is to be appreciated for his restraint. Polemic could easily overwhelm the story here and he has chosen to tell it through characters for whom such discourse would feel unnatural at best, a mask for authorial intrusion at worst. Instead, he drops a reference here and there and lets the impact of a sentence ripple through the text, allowing us to go on with the story or pause of our own accord to consider the implications, never himself stopping the flow of the narrative to tell us what we should be inferring at a given moment.

Because as much as this is a novel about a catastrophe and its impact on the people involved, it is more a novel about finding purpose, coming home, and doing right. For all the vast implications of what has happened in Switchcreek — and which may happen anywhere else at any time — and all the fascinating speculation about what that something is, The Devil’s Alphabet is a fine work of fiction because it is about these few people and their lives, their struggle to cope with the ambivalence of a universe which really does seem to play dice.

Gregory lays out a rather interesting theory of why this may have happened, based on quantum tunneling and a facet of the many-worlds model of the metaverse. It may not be what has happened, he doesn’t go there, it’s just a theory, one among several developed by people who don’t know and who still need an explanation. It’s the human urgency for something rational, no matter how far-fetched, that is important, not the one of several Sfnal conceits that he may favor. Why and how this happened is less important than the fact that it has happened, and these people must deal with it.

The central issue that transcends the specifics of the story, however, is one that is recurrent in science fiction, never answered, always vital — what does it mean to be human? The genre has perhaps grown comfortable, if not complacent, with that question posed in the form of extraterrestrials. In some sense, we’ve come of age through learning to cope with the idea of other sentient, sapient species in the universe. But the universe itself, in this instance, provides a comforting buffer, a distance. The question becomes more pointed when that Other Species is right here, living with us.

But that’s what stories of the prodigal are all about anyway. The son who goes away to strange lands, sees odd things, learns peculiar truths, and comes home changed. Comes home different. Not one of us anymore. Is he still “like us?” The welcome he gets, of course, says more about those who never left than it does about the returning child.

[…] But the pay-off, which every writer would do well to keep in mind, is when someone picks up their work and comes away fundamentally affected, changed, with a new perspective. Preaching doesn’t accomplish that. Something simple — like treating all characters, male or female, whatever orientation or ethnicity, as People first and foremost — can have amazing consequences. Mark W. Tiedemann is the author of Remains, Realtime, and several other novels. His last article for us was The ABC’s of DNA and Other Thorny Themes: Daryl Gregory’s “The Devil’s Alphabet” […]