Goth Chick News: A Curiosity “From Hell”

Between August 31st and November 9th, 1888, the first widely documented serial killer known as “Jack the Ripper” brutally murdered five prostitutes in the heinous poverty that was the Whitechapel area of London.

In 2010, a Google search on “Jack the Ripper” returns over 2 million entries, and Amazon lists 605 books and 64 movies, all focused on an unsolved mystery that is 122 years old and which frankly, by today’s standards would hold the headline spot on CNN for a week at most.

I had to literally ask myself why?

Meaning I’ve been right there fascinated along with everyone else.

I’m not sure when I first became aware of Jack and his bloody doings, but I do recall that taking the after dark “Jack the Ripper Tour” was high on my list of priorities when I packed off to London the first time.

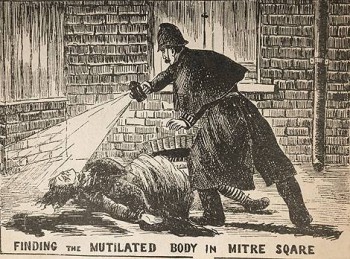

There on a perfectly damp and foggy evening I, along with a couple of dozen other tourists, followed a guide wearing a fairly cheesy black cape and top hat through some very fragrant Whitechapel alleyways. And though this neighborhood is a mostly respectable industrialized area today, it doesn’t take much encouragement to imagine coming upon the mangled mess of Polly Nichols spread unceremoniously across the wet bricks.

OK, now that I’ve engaged your gag reflex and you’re thinking I should try going someplace nice like Vegas next time, I will tell you that at that moment I completely understood the term “morbid fascination.”

I took that tour many times in my subsequent pilgrimages to London, and dragging through those rank alleyways became almost an addiction. The evenings even concluded with a visit to The Ten Bells pub, which is still in operation today due to its historic status.

It was from the Ten Bells that Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s final victim, was last seen leaving in the company of a well-dressed gentleman wearing a cape and top hat. Standing in that original building, on floor boards warped by nearly 200 years of spilt libations, you can almost see a shadow in a topper, sliding past the front window.

Gentleman Jack would like to buy you a drink and discuss a little business outside, if you’ve got a moment.

I’ve seen all of the movies and own a fair number of those 605 titles Amazon lists as dedicated to this subject, and many of them rehash the same well-documented facts about the case. More than a few dabble in mostly wild speculation on the killer’s identity, which runs the gambit from a mad Freemason to Queen Victoria’s drug-addled personal physician.

However, as you have come to expect, I have a few favorites, which all manage to recreate that morbid and arguably unhealthy fascination I feel standing in Whitechapel at midnight.

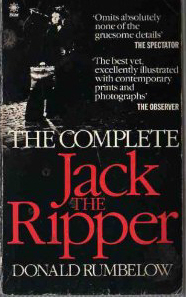

First on the list, The Complete Jack the Ripper, came to my attention via the author himself, Donald Rumbelow.

First on the list, The Complete Jack the Ripper, came to my attention via the author himself, Donald Rumbelow.

For over sixteen years Mr. Rumbelow has acted as a guide on certain nights for the London after-dark tour, and on my second go at chasing Gentleman Jack I was lucky enough to choose one of his evenings.

When the tour concluded at The Ten Bells, I stayed behind to chat with Mr. Rumbelow about the case, learning that he had just published the definitive work on the murders, following a distinguished career as a London police officer and curator of The Police Crime Museum. He proudly produced a copy from his bag and signed it for me.

It wasn’t until I got home that I discovered I had just shared a couple of pints with the world’s leading expert on the Ripper crimes. Mr. Rumbelow has consulted on movies, documentaries, and a BBC series, and his book is a riveting account of the events in 1888 not just from a factual standpoint, but from a police investigators viewpoint. It’s definitely the place to introduce yourself to Jack.

In this work you’ll read about the hundreds of taunting letters, supposedly from the killer, which were sent to the London police department. Most of these are considered frauds, written either by hoaxers attempting to incite more panic or by newspaper reporters attempting to create something solid out of a profound mystery.

However, several of these letters have come to be considered authentic. In the letter known as “Dear Boss,” the author makes an eerily accurate prediction that as part of his next violent act, he “shall clip the lady’s ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly.”

Three days later on September 30, the night the Ripper took two victims, one of the bodies was found to have had the earlobe removed though it never found its way into the post. This is also the letter in which the author refers to himself as “Jack the Ripper;” a self-awarded moniker with definite staying power.

On October 16th George Lusk, the president of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received a three-inch-square cardboard box in his mail. Inside was half a human kidney preserved in wine, along with the following letter. Medical reports carried out by Dr. Openshaw found the kidney to be very similar to the one removed from Catherine Eddowes, the second victim from the night of September 30th. The letter read as follows:

From hell.

Mr Lusk,

Sir

I send you half the kidney I took from one woman and preserved it for you the other piece I fried and ate it was very nice. I may send you the bloody knife that took it out if you only wait a while longer.

You can read about the case and the other letters here.

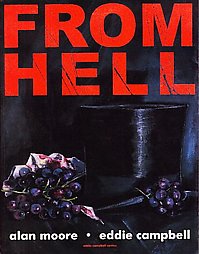

103 years later Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell used the first words of this letter for their famous comic adaptation From Hell.

103 years later Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell used the first words of this letter for their famous comic adaptation From Hell.

In 2001, Hollywood turned Moore and Campbell’s opus into From Hell starring Johnny Depp as a Scotland Yard inspector, and Heather Graham as the ill-fated Mary Kelly. The Ten Bells even makes a cameo.

It wasn’t exactly a blockbuster and Johnny Depp probably doesn’t want to discuss it these days, but it’s an interesting and rather novel approach to a series of events about which most people are at least somewhat familiar.

I just watched it again to be sure I really remembered liking it for a reason other than Johnny Depp, and I did.

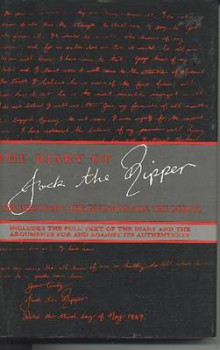

Finally, though there continues to be speculation to this day about the true identity of the killer, none of these theories mattered in 1993 when The Diary of Jack the Ripper was published.

Supposedly it was discovered during a home restoration project and written by James Maybrick, a wealthy Victorian cotton merchant who was already famous for having been poisoned to death by his wife.

Supposedly it was discovered during a home restoration project and written by James Maybrick, a wealthy Victorian cotton merchant who was already famous for having been poisoned to death by his wife.

The diary indicates that Maybrick was an addict whose deteriorating mental condition turned him into a delusionary murderer of prostitutes in Whitechapel.

Many of the facts put forth in the diary entries match amazingly well with those of the case, including several that were not widely known, and one in particular that had never been released to the public.

A grisly crime-scene photo of the body of Mary Kelly shows the letters “FM” written in blood on the wall above the bed. The diary explains this as the initials of Florence Maybrick, James Maybrick’s wife, about whom he was imagining as he carried out his violent deeds.

I found the diary fascinating and believed, along with many, that the mystery of Jack the Ripper had finally been solved.

I found the diary fascinating and believed, along with many, that the mystery of Jack the Ripper had finally been solved.

So it was with much disappointment that I read several years later that forensics, and a more careful analysis of the content, pointed to it being a very clever forgery.

I still recommend it mainly because its authenticity has never been conclusively proven or disproven, and even if it is fake, the author does an amazingly detailed job explaining the brutalities of life in what is widely considered a romantic period in history.

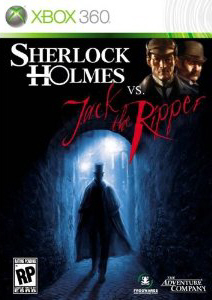

On April 20 Dreamcatcher games will release Sherlock Holmes Vs. Jack the Ripper for the Xbox.

On April 20 Dreamcatcher games will release Sherlock Holmes Vs. Jack the Ripper for the Xbox.

Clearly “Gentleman Jack” is still haunting the 21st century, beckoning from the alleyway to meet him in the shadows for a little chat.

But if you go, be warned, once you take him up on his invitation, you may never get him to go away.