Forgive Me, Solomon Kane, For I Once Wrote a Screenplay about You

The movie Solomon Kane has gotten released in the U.K., and although it doesn’t have U.S. distribution yet, we will eventually see it on this side of the pond, either in theaters or on DVD. A Solomon Kane movie after so many years of patient waiting is a sword-and-sorcery/Robert E. Howard lover’s dream. But Al Harron at The Cimmerian, who has seen the movie in the U.K., doesn’t have a high opinion of the Howard-side of the results. Although he thinks the film “wasn’t that bad.” His detailed analysis is definitely worth reading, although the spoiler-wary should know that it contains many significant plot details.

The movie Solomon Kane has gotten released in the U.K., and although it doesn’t have U.S. distribution yet, we will eventually see it on this side of the pond, either in theaters or on DVD. A Solomon Kane movie after so many years of patient waiting is a sword-and-sorcery/Robert E. Howard lover’s dream. But Al Harron at The Cimmerian, who has seen the movie in the U.K., doesn’t have a high opinion of the Howard-side of the results. Although he thinks the film “wasn’t that bad.” His detailed analysis is definitely worth reading, although the spoiler-wary should know that it contains many significant plot details.

I have a personal link to any Solomon Kane film project, and not just because Howard’s puritan adventurer is my favorite of his characters and also the one most suited for the silver screen. It’s mainly because I actually wrote a Solomon Kane screenplay in the mid-‘90s, when I was just out of college, working as an apprentice editor in Warner-Hollywood Studios, and flush with the desire to become a great screenwriter.

Those were such innocent years. . . . I’ve abandoned the film business entirely, and once I wrote my first novel I knew that I never wanted to return to the screenplay format again: it wasn’t my type of storytelling, and I’d much rather have someone else tell me a story through a completed film. I now want to write novels, and if they ever sell as film properties, that’s wonderful—but even if I were offered the opportunity to do a first pass on the screenplay version, I’d still prefer someone else do it. Someone with some distance from the material.

Only back in those neophyte days could I have dared something like a Solomon Kane screenplay. I almost never write pastiche or fan fiction; my Solomon Kane script was my second pastiche work and is so far my last. (The first was a James Bond novelette written in 10th grade as an angry reaction to the terrible John Gardner novels of the day.) I never feel comfortable writing about classic characters, and Howard is an especially frightening and intimidating fellow to follow.

I realized this somewhat back then, which is one reason that I altered the character and disguised him under a different name: Michael Sparrow. (Oh, I had a jolly laugh when the lead character of The Pirates of the Caribbean franchise years later was also given the surname “Sparrow.”) I was also thinking, optimistically, about trying to sell the script, and a “new” character was necessary for this. I had it figured out this way: if I did sell the screenplay, I could try to convince the production company to purchase the rights to Howard’s Solomon Kane, and then I would change the character’s name back to Solomon Kane as well as some other details. For example, I gave my character a magical knife, a gift from an Arab mystic, instead of a juju staff from an African shaman. Simple, quick fix, if necessary.

Ludicrously ambitious thinking. But I was twenty-three, and I needed to give a dream-project a shot.

I soon discovered that when you change a character’s name and a few details about him, you also inevitably start to change other aspects of his story. Michael Sparrow began to develop a different feeling than Solomon Kane, and my own historical interests and extensive research into English Puritanism pushed the story further from Howard’s territory. Honestly, I didn’t really understand Solomon Kane that well in 1996, having only read the Baen paperback collection, and not that deeply.

But what really shifted my whole approach was my choice of backdrop. Zeroing in on events that could have happened near 1600 and Solomon Kane’s career, I picked up on the search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke as the through-story. Not only did it occur in the right time (1587), but it allowed for sea voyages, pirate attacks, and a chance for a supernatural occurrence to account for the vanishing of the first English colony in what would eventually be the United States of America.

So I ended up with a outline for a script more akin to Howard’s “The Black Stranger” than anything Solomon Kane. I even titled the screenplay Black Sparrow, although this was also a nod to Howard’s and Cornell Woolrich’s obsession with sticking the word “black” in many of their titles.

Once I started research on Roanoke, I seriously couldn’t stop. Fascinating stuff. I read just about every piece of primary documentation about the original settlement and the first search for it that was available. Roanoke took over the script as I tried to craft as realistic a background as I could, using historical figures when possible, before I brought on the fantasy elements. John White, the governor of the colony who was returning to try to rescue it, evolved into the co-protagonist with Michael Sparrow, and started becoming much more interesting. I envisioned Patrick Stewart playing the part (Michael Sparrow was played by Christopher Walken), and he really spoke to me as I wrote more than my pseudo-Solomon Kane. I turned John White into the grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first girl born into the colonies, whom I aged up into a teenager. White therefore had an even more desperate and personal reason to find the lost colonists aside from his responsibility as their governor. Captain Spicer, who helmed the main ship on the expedition, was also a major character. Each of the colonists was given the name of one of the actual settlers.

Once I started research on Roanoke, I seriously couldn’t stop. Fascinating stuff. I read just about every piece of primary documentation about the original settlement and the first search for it that was available. Roanoke took over the script as I tried to craft as realistic a background as I could, using historical figures when possible, before I brought on the fantasy elements. John White, the governor of the colony who was returning to try to rescue it, evolved into the co-protagonist with Michael Sparrow, and started becoming much more interesting. I envisioned Patrick Stewart playing the part (Michael Sparrow was played by Christopher Walken), and he really spoke to me as I wrote more than my pseudo-Solomon Kane. I turned John White into the grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first girl born into the colonies, whom I aged up into a teenager. White therefore had an even more desperate and personal reason to find the lost colonists aside from his responsibility as their governor. Captain Spicer, who helmed the main ship on the expedition, was also a major character. Each of the colonists was given the name of one of the actual settlers.

So what is my ersatz Solomon Kane doing here? In a prologue—my pre-credits James Bond sequence—I had Michael Sparrow in the south of France, pursuing a black magician named Christopher Gerard who had killed a young girl to use her blood in one of his ceremonies. In a direct reference—the only reference—to any of Howard’s Solomon Kane stories, I had Sparrow find the girl dying in the woods. She tells him who attacked her and drew her blood, then expires. Sparrow says, “Men shall die for this.” Right from “Red Shadows.” Because that is such a damn cool line.

But the evil sorcerer escapes Sparrow’s vengeance, and Sparrow vows to chase him to the ends of the earth. Gerard manages to get across the Atlantic by joining the original colony that settled at Roanoke. Sparrow pledges his service as a fighter on John White’s expedition so he can track down Gerard. He’s certain Gerard is behind the colony’s strange silence.

And what did happen to the colony? Here I leaped into crazy speculation and pulled out the sword-and-sorcery nuttiness (there was already plenty of action, what with the Spanish wanting to sink any English ship they come across). It turns out that near to Roanoke on the island of Croatoan—the explanation for the the word “Croatoan” carved into a fort post that the historical expedition found—lie the ruins of a city built by ancient Phoenicians who crossed the Atlantic during the Bronze Age. They brought with them the idol of their dark god Baal-Reseph. When the Phoenicians died out, the evil spirit was left imprisoned. Gerard found it, freed it, and controlled it. He then turned its power loose on the colonists and nearby native tribes, turning them into creatures called “Mantoacs,” zombie-like animal-hybrid creatures.

Michael Sparrow and John White’s men round up the few survivors, make a treaty with the natives, and fight a battle against Gerard, his slaves, and the demon Baal-Reseph. Bad guys die. Michael Sparrow has a huge sword-duel with a dastardly Germany mercenary and confronts Baal-Reseph and slays it with his magical knife. Virginia is re-united with her grandfather. The surviving colonists elect to stay with the natives, and the expedition returns to England with the story that “we couldn’t find them.” Michael Sparrow takes a canoe into the North American interior on further adventures that will never be written.

The final script wasn’t very good. I was not skilled enough at that age to make Black Sparrow anything but average and often silly. I’m still amazed that I showed it to people. It was a big undertaking, and looking back over it I do think there’s a good fantasy adventure tale to make out of the Lost Colony. But Solomon Kane isn’t supposed to be in it, and I should have waited to write it in prose form.

(I’m proud of one line in the script: when John White tells Sparrow that he was unable to return to the colony earlier because of the Spanish Armada, Sparrow replies, “Catholics never come at a good time.” Not something the real Solomon Kane would speak, but I really couldn’t resist having an English puritan say that.)

I hope that soon I can sit in a theater and say: “Well, the movie wasn’t a genuine Solomon Kane story, but it sure was better than what I wrote fifteen years ago.” Worst case scenario, I say: “Hell, even my story I wrote fifteen years ago was better than that.”

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning author. He received the Writers of the Future Award in 2011 for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and has two stories forthcoming in Black Gate and a number of ebooks on the way. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com and follow him on Twitter.

About ten years ago I did read a piece of fiction which tried to give an explanation for Croatoan (I think time travel was involved) – but I can’t remember *anything* more about it, not even whether it was a story or a novel.

(That’s really not much help….)

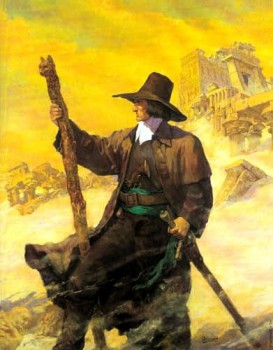

I have to say — I love Solomon Kane added there in the background. That cracked me up. It was subtle, too, so that I didn’t notice it when I first saw the pic. Nice joke.

That screenplay sounds awesome. The storyline, at least.

I always thought it odd that Howard had his English Puritan milling about in Africa so much yet never had him once set foot in New England. Or Virginia, for that matter.