“The Fire of Asshurbanipal”: The First Time I Met Robert E. Howard

Today’s is Robert E. Howard’s birthday—I’ve always felt pleased that it lies so close to mine, as January is a lonely month in which to have your birthday—and for my gesture to commemorate the Great Lord of Blood, Thunder, and Thick Mountain Accents, I’m going to take a short glance back at my first encounter with him, in the story “The Fire of Asshurbanipal.”

Okay, I lied. It’s not short . . .

“The Fire of Asshurbanipal” was first published in Weird Tales in December 1936, almost half a year after Howard’s death. It is one of three completed stories that the author’s father, Isaac Howard, submitted to Weird Tales after his son’s death (this according to a letter he sent to Howard’s literary agent, Otis Adelbert Kline). The other two stories are “Dig Me No Grave,” and “The Black Hound of Death.” All saw print in the Unique Magazine in late 1936 and early 1937. However, “The Fire of Asshurbanipal” may have been written earlier, possibly around the time of “The Black Stone” in late 1930 (both reference the name ‘Xuthltan’) when Howard was experimenting with H. P. Lovecraft’s themes and concepts. A second, non-fantasy version of the story exists, which suggests to me that Howard was considering selling it to Adventure or a similar magazine.

I discovered the story, and Howard himself, through H. P. Lovecraft, whom I had in turn discovered through an interest in the pulps in general that started with my appreciation of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Cornell Woolrich. Lovecraft is the principle “gateway author” of my life. No other writer has done such a fine job of introducing me to so many other great authors. I met not only Lovecraft’s contemporary correspondents, like Clark Ashton Smith, Henry Kuttner, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and August Derleth; but also the writers who influenced him, like Lord Dunsany, Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, and Arthur Machen; and the writers who followed after him, such as Ramsey Campbell and Brian Lumley.

I discovered the story, and Howard himself, through H. P. Lovecraft, whom I had in turn discovered through an interest in the pulps in general that started with my appreciation of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Cornell Woolrich. Lovecraft is the principle “gateway author” of my life. No other writer has done such a fine job of introducing me to so many other great authors. I met not only Lovecraft’s contemporary correspondents, like Clark Ashton Smith, Henry Kuttner, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and August Derleth; but also the writers who influenced him, like Lord Dunsany, Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, and Arthur Machen; and the writers who followed after him, such as Ramsey Campbell and Brian Lumley.

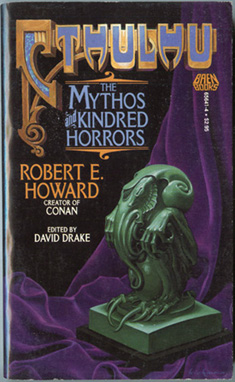

And of course, H. P. introduced me to Robert E. Howard. I knew the fellow’s name and that he wrote the Conan stories, but little more than that. This was in the early 1990s, during my college days in Minnesota, and Howard was in a serious pubishing slump: the Baen series hadn’t started yet, the Ace Conan’s were almost gone, and I knew nothing of the Donald Grant editions. I stumbled almost by accident upon the Baen volume of Howard horror tales called Cthulhu: The Mythos and Other Kindred Horrors, edited by David Drake, of whom I knew nothing at the time either, in the Midnight Special bookstore in Santa Monica (alas, now gone the way of too many independent bookstores and other ancient civilizations) when home on Summer break. I snatched up the book, imagining that I would find more pastiche Lovecraft–Cthulhoid tales of the type I had found in the works of Derleth.

I don’t remember the reason, but I skipped the first story in the collection, “The Black Stone,” the most Lovecraftian-imitation in Howard canon’s, and plunged into the second, “The Fire of Asshurbanipal.” The title grabbed my attention. I’m a lover of ancient Middle Eastern history, and the name of the great Assyrian ruler drew me to the story right away. I’m thankful I chose this for my first experience with the great Texan; “The Black Stone,” although a good story, is not as good an introduction to Howard.

I recall the shock of the quick succession of opening paragraphs:

Yar Ali squinted carefully down the blue barrel of his Lee–Enfield, called devoutly on Allah and sent a bullet through the brain of a flying rider.

“Allaho akbar!”

The big Afghan shouted in glee, waving his weapon above his head, “God is great! By Allah, sahib, I have sent another one of the dogs to hell!”

His companion peered cautiously over the rim of the sand-pit they had scooped with their hands. He was a lean and wiry American, Steve Clarney by name.

“Good work, old horse,” said this person. “Four left. Look—they’re drawing off.”

Whoa! We aren’t in Lovecraft country anymore, Toto. This writer must be the guy who wrote Conan! And there are already dashes of the Western (the classic Lee–Enfield gun), Rudyard Kipling, and H. Rider Haggard. This writer had hooked me already; this was going to be different, this was going to be a rush. Apparently, this “Cthulhu Mythos story” belonged to the “swords in the desert” genre that I had grown to love from my study of Middle Eastern history.

The rest of “The Fires of Asshurbanipal” bore this out. A Lovercraftian tone started to settle over the story as the heroes entered a lost desert city, but then switched to an exciting brawl described in bone-crunching detail as the heroes confronted human foes in the form of Clarney’s old enemy Nureddin el Mekru and his band of Bedouins. The finale switched back to Weird Tales horror with yet another “indescribable” horror out of the Cthulhu playbook, but at the end, instead of Mythos Dread, I was left with a sense of exhausting exhilaration, the thrill of seeing tough characters skirt the edge of danger and madness and emerge—changed, but still holding onto the vitality of survival, which is ultimately all that seemed to matter to them.

When I look back on the story now, I can’t think of a more perfect introduction to the realm of Robert E. Howard. Here was Howard, probably in the mid-point in his career, confronting the concepts of a respected colleague, but transforming them seamlessly into his own style.

Our stalwart heroes in this adventure are Steve Clarney (perhaps a derivation of the Irish name Clancy, a logical guess considering Howard’s predilection for Irish adventurers), an American adventurer in the mold of Francis Xavier Gordon and Kirby O’Donnell, and his loyal companion, the Afghan Yar Ali. These two have a camaraderie similar to that found between Peachy and Daniel in Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King. They’ve also located themselves squarely in H. Rider Haggard territory, following the instructions left by a dead man to lead them to a lost city of treasure, the same plot device that got Haggard’s famous adventure novel King Solomon’s Mines off and running. Although an American and an Arab, Clarney and Yar Ali treat each other with equal respect throughout, Yar Ali’s use of the customary term sahib excepted.

But Howard, master of plot compression for the pulps, starts us off in media res, as Clarney and Yar Ali fight for their lives against Bedouin raiders long after their quest has gone wrong. Howard shoots readers into the action, involves them in the characters’ struggles, and then explains the background in pieces. “The Fires of Asshurbanipal” shows how excellent Howard was at plot structure; his gradual release of information about the story to build the tension is nearly perfect.

Clarney and Yar Ali are hunting for a gem called (surprise!) the Fire of Asshurbanipal. Howard had a great love of Assyrian names and themes; many of the early Conan stories use pseudo-Assyrian backdrops. Here he actually delves into Assyrian history, although in a mythic, pulp-adventure way. Asshurbanipal was an actual king of Assyria, the most powerful and also the last of importance. He came to the throne in 668 B.C.E. He conquered Egyptian and quelled a rebellion in Babylonia. He died in 626 B.C.E. His two successors frittered away his conquests and power, and an alliance between the kings of Babylon and Media managed to conquer Assyria in 606 B.C.E., turning it into a province of what would soon become the Persian Empire. The Assyrian capital of Nineveh was razed to the ground.

Clarney and Yar Ali are hunting for a gem called (surprise!) the Fire of Asshurbanipal. Howard had a great love of Assyrian names and themes; many of the early Conan stories use pseudo-Assyrian backdrops. Here he actually delves into Assyrian history, although in a mythic, pulp-adventure way. Asshurbanipal was an actual king of Assyria, the most powerful and also the last of importance. He came to the throne in 668 B.C.E. He conquered Egyptian and quelled a rebellion in Babylonia. He died in 626 B.C.E. His two successors frittered away his conquests and power, and an alliance between the kings of Babylon and Media managed to conquer Assyria in 606 B.C.E., turning it into a province of what would soon become the Persian Empire. The Assyrian capital of Nineveh was razed to the ground.

And here Howard postulates his lost city of Kara-Shehr, inserting fantasy into the history: “Possibly, thought Steve, Kara-Shehr—whatever it’s name had been in those dim days—had been built as an outpost border city before the fall of the Assyrian Empire, whither survivals of that overthrow fled. At any rate it was possible that Kara-Shehr had outlasted Nineveh by some centuries—a strange, hermit city, no doubt cut off from the rest of the world.” Clarney cannot understand what lead to the ruin of the city, however, and here Howard starts to graft Lovecraftian elements onto the already rich brew of adventure and history and mythic archaeological speculation.

In a major exposition speech, the kind only an excellent pulp writer like Howard could exectue, one of Nureddin’s older companions explains the history of the pulsing red stone that his master desires in order to warn him not to touch it. Apparently Steve Clarney’s early guess about when Kara-Shehr was inhabited was incorrect: it did not outlast the reign of Asshurbanipal. The wizard Xuthltan (a name that might presage Xaltotun in The Hour of the Dragon) who uncovered the red stone from a deep cavern fled to the outpost city from the court of Asshurbanipal when the king blamed the evil befalling his kingdom on the sorcerer’s stone. But the ruler of Kara-Shehr desired the stone and tortured Xuthltan to death to get it. The dying sorcerer summoned the guardian demon from the cave, and it slew the king, leaving his corpse on his throne still clutching the stone. Everyone within the city died from the demon’s wrath. (The Bedouin, when he tells the story, specifically uses the term djinn, an Arab word for free-will spirits made from smokeless fire; they can be any shade of good or evil, but you should probably avoid all incarnations.)

But even before the demon/djinni/Great Old One wiped out Kara-Shehr, it was already a frightful place. There was something . . . different . . . about the builders of Kara-Shehr, and Howard makes this attribution to all of the mysterious ancient east: “. . . the builders of Nineveh and Kara-Shehr were cast in another mold from the people of today. Their art and culture were too ponderous, to grimly barren of the lighter aspects of humanity, to be wholly human, as modern man understands humanity. Their architecture repellent; of high skill, yet so massive, sullen, and brutish in effect as to be almost beyond the comprehension of moderns.” (Emphasis mine.)

Howard here, I believe, latches onto an important concept in Lovecraft and makes it his own in his style of fantasy. Lovecraft’s stories often visit cities constructed by inhuman minds, such as the maddening metropolises of “The Shadow out of Time” and “At the Mountains of Madness.” But these architects were in no way even anthropoid, and humans’ inability to comprehend, or even tolerate, such styles makes natural sense. But Howard suggests here that historical humans have at times been capable of architecture so removed from modern paradigms that they become inhuman. I think anyone who has gazed at the strange, beautiful, but distant art of Assyria, Babylon, or ancient Sumer can appreciate Howard’s description and insight here through Clarney’s eyes. Howard certainly must have studied photos of archaeological digs and developed this sense of utter alien-ness within historical culture, something almost frightening. He was probably also influence by the Sabaean myth of the lost city of Irem, which supposedly drowned in an ocean of sand because of its affront to the gods.

And so Howard cleverly (or perhaps unconsciously, if he was writing this story at his usual furious speed) grafts the alien mythos beings into his fantasy-historical-adventure setting, where two tough adventurers can confront the unfathomable of a Lovecraftian nasty, and emerge intact on the other end. Changed, but not destroyed. The last few paragraphs utilize a common Lovecraft trope, one that Derleth would employ over and over again in his pastiches: the post facto revelation of the horror that had previously gone undescribed when the characters confronted it. Clarney here describes a distinctly Cthulhoid creature (wings, tentacles, “toadish”), offers a few passages about cosmic creatures the Assyrians may have summoned, and swears never to speak of it again. But this Lovecraftian conclusion is counterbalanced by the paragraph before: “Steve made no reply until the comrades had once more swung into the saddle and started on their long trek for the coast, which, with spare horses, food, water and weapons, they had a good chance to reach.”

Thus, the act of survival softens the Mythos mind-warping horror. Steve Clarney and Yar Ali were almost certainly dead men at the start of the tale: low on ammo, almost out of water and food, stranded in the middle of the desert with Bedouin hunters on their trail. They pass through a brutal brawl and encounter with an unearthly horror, and come out alive and ready to trek onward.

This story told me what to expect when I would finally meet Howard’s Conan: struggle, horror, and the face of death peering around every corner. But the hero crashes, smashes, and slashes through. Changed maybe, seriously injured, but alive, and thankful to have another day to face death again.

Later in this same volume, I would encounter what has since become my favorite Robert E. Howard story, “Pigeons from Hell.” But “The Fire of Asshurbanipal” still has a special meaning for me because it introduced to one of my favorite authors using ideas I could personally access so quickly.

All in all, a very Happy Birthday to Bob Howard. I hope the mead in Valhalla is strong and battles each morning glorious.

“The Fire of Asshurbanipal” is a great tale! My favorite Howard story is also in this Cthulhu collection: “The Valley of the Worm.” What a great paperback!

Haven’t read “TFoA” myself, but thought I’d agree with you on enjoying the proximity of REH’s birthday to my (our) own 🙂

[…] week, when I answered to call to a group celebration of Robert E. Howard’s birthday, I originally chose to write about his breakthrough short story, “Wolfshead.” Somehow, I got […]

Haven’t read “The Fire of Asshurbanipal” yet, though i’m familiar with Roy Thomas’ lukewarm adaptation to Conan, “The Hell-Spawn of Kara-Shehr”.

The more i become familiar with Howard’s works, greater is my disappointment with Thomas’ writing in Conan…

But speaking of more interesting things, i came across what might be either an obscure reference on Howard’s part or just an incredible coincidence, check it out: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karasahr