Clash of the Titans: The Alan Dean Foster Novelization

Update: Alan Dean Foster has generously provided some comments of his own about the novelization. Please see the comments section.

Update: Alan Dean Foster has generously provided some comments of his own about the novelization. Please see the comments section.

2010: The Year We Remake Clash of the Titans.

I have never thought that re-making Ray Harryhausen’s final movie, the 1981 telling of the Myth of Perseus and Medusa, was a smart idea. I don’t, in principle, oppose re-makes (what good would that stance do in these strange times anyway?), but the original Clash of the Titans is a 100% auteur film, a movie that exists because Ray Harryhausen did the stop-motion effects. Harryhausen defines the movie. Any re-make would simply tackle an old myth with new—and not necessarily more interesting—effects to cash-in on Generation X name recognition. And then when I actually read the plot description of the 2010 Clash, I shook my head in mystification . . . this Hades vs. The Other Gods concept is antithetical to Greek Mythology. The original Clash alters many elements of Perseus’s story, but it still feels similar to how the Archaic and Classical Greeks must have imagined their Heroic Age.

A deeper reason that I’m doubtful of the re-tooled Clash of the Titans is the enormous personal investment I have in the original film. No other movie from my childhood has had such a direct effect on my later interests as an adult. Unlike many childhood loves, Clash of the Titans holds up perfectly today; the magic remains, and many scenes still give me shivers. Nostalgia alone does not carry the film; it can carry itself quite proudly.

But . . . I’m not here today to review the original Clash of the Titans. I’m planning to do an extensive analysis of it later this month, but for the first post of 2010 I’ve decided to take a different tactic as a warm-up and approach Clash of the Titans from a side road; a road rarely taken in film or book critiques: the movie novelization.

Novelizations of films have existed since the silent movie era, but the 1970s and ‘80s were the heyday of the form, with most A-list genre films getting the book treatment. Although many critics have written about how novels have been adapted to the screen, not many have looked into the reverse process. Because most novelizations are written on short schedules by second-tier authors, they tend to be lackluster as literature; the lack of critical interest in them isn’t surprising. I rarely read novelizations myself, yet I’ve always had a fascination with the process of what goes into creating one, “reverse engineering” a visual product into prose. In terms of structure and dialogue, movies resemble short stories more than novels, and changing a movie into the long prose form requires some unusual tweaking, especially in creating internalized thought and multiple points-of-view. Novelizations also reveal details about the making of the movie: since the book must reach retails shelves ahead of or on the movie’s release date, the author rarely gets to see the finished product and has to work with earlier drafts of the script and rough cuts of the film. Novelizations never reflect the final cut of the movie, containing abandoned concepts, excised scenes, and sometimes radically different endings.

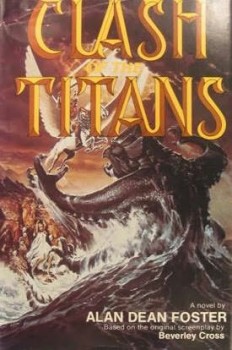

Alan Dean Foster is the reigning King of the Novelization. From the late-‘70s until the mid-‘80s, he seems to have written the tie-in novel for every science-fiction or fantasy film of major success or cult adoration. The list is awe-inspiring: Alien, The Black Hole, The Thing, Outland, Starman, Krull, The Last Starfighter, Pale Rider, Aliens, and something called Star Wars written under the pen name “George Lucas.” If Blade Runner weren’t already based on a novel, you can bet that Foster would have written the novelization for that as well. It’s astonishing that he didn’t ghost write Star Trek: The Motion Picture for Gene Roddenberry (he has story credit on the film, but he didn’t write the novelization). However, the Trek karma got around, resulting in Foster writing the novelization for last year’s Star Trek re-launch.

Alan Dean Foster is the reigning King of the Novelization. From the late-‘70s until the mid-‘80s, he seems to have written the tie-in novel for every science-fiction or fantasy film of major success or cult adoration. The list is awe-inspiring: Alien, The Black Hole, The Thing, Outland, Starman, Krull, The Last Starfighter, Pale Rider, Aliens, and something called Star Wars written under the pen name “George Lucas.” If Blade Runner weren’t already based on a novel, you can bet that Foster would have written the novelization for that as well. It’s astonishing that he didn’t ghost write Star Trek: The Motion Picture for Gene Roddenberry (he has story credit on the film, but he didn’t write the novelization). However, the Trek karma got around, resulting in Foster writing the novelization for last year’s Star Trek re-launch.

(And, yes, I own all of the above-mentioned books. Collecting Alan Dean Foster novelizations is a small hobby of mine.)

Alan Dean Foster’s Clash of the Titans novelization was published by Warner Books during one of the author’s busiest movie-adapting periods. Foster’s novelizations are of high quality for the form (I think his version of The Black Hole is superior to the film), and his familiarity with speculative fiction makes him sure-footed with the material. Clash of the Titans is no exception; it provides a good reading experience with a few surprises along the way and some fine passages that catch a bit of the movie’s magic.

What makes the Clash of the Titans novelization unusual is how closely it resembles the on-screen product. This is probably due to the meticulous preparations that Ray Harryhausen and his producing partner Charles H. Schneer had to put into all of their movies, and the length of time needed to complete the effects work after principle photography wrapped. The intricate nature of the stop-motion set pieces and the restrictions of budget required extensive pre-production planning (the reason that the movies are not “director’s films”). Most of Clash of the Titans’ script would have already been locked down and the special-effects sequences storyboarded and choreographed before Foster started his work. Although the book cover credits Beverly Cross with the original screenplay, Harryhausen probably deserves much of the credit for Foster’s source material.

Most of the differences between the movie and the book are standard for a novelization: longer, more-expository dialogue, internalization of character’s thoughts, and descriptions of backstory that are unnecessary on screen. Although some of the longer dialogue scenes may reflect earlier versions of Beverly Cross’s script or edits made to the final cut, most feel like Foster’s own inventions to make the terser screen conversations fit better into the three hundred pages he had to fill.

Chapter I immediately shows how an author must approach a film-to-novel transformation. The movie opens on shots of soldiers of Argos on a storm-whipped shore carrying the ark/coffin meant to hold Danae and the infant Perseus. Foster’s book starts with a description of the setting, mention of the gods, and a few paragraphs about scuttling crabs, before the writing lens focuses on the soldiers carrying the ark. Foster then dips into the men’s thoughts and doubts about the task ahead of them as they prepare to send Danae and son to their deaths.

The only dialogue the film has in this scene is the fierce announcement that Acrisius, King of Argos, makes to the sky. It contains all that the viewer needs to know based on the visual information already provided:

Bear witness, Zeus, and all you gods of High Olympus! I condemn my daughter Danae and her son Perseus to the sea. Her guilt and sin have brought shame to Argos. I, Acrisius the King, now purge her crime and restore my honor. Their blood is not on my hands. Now!

Not only is this the sole line in the scene, it’s the only line that Acrisius speaks in the film. At his final “Now!”, Danae and Perseus are locked into the ark and heaved into the Aegean. Perfect economy, and it works ideally on screen. An upcoming scene explains that Perseus is the son of Zeus, thus explaining Danae’s “shame”; Acrisius’s speech implies that the boy is illegitimate.

This is too brief for a novel, so Foster has Danae making a half-hearted escape attempt, followed by an angry exchange between her and the man about to send her to a watery doom. After this dialogue, Acrisius gets more descriptive in his invocation, trying to distance himself from the murder he is about to commit:

Bear witness, Great Zeus, and all you gods of High Olympus! I commit my daughter Danae and her bastard son Perseus to the sea. Her guilt and sin have brought shame to Argos. The people demand their justice, and I do my duty as their king. I, Acrisius the King, now purge her crime and restore my honor and the honor of the royal family.

Her blood is not on my hands. It springs from her own actions and from the vileness that resided in her loins. From that moment she ceased to be Danae of Argos. From this moment she is no longer anything. . . . Now.

Does this derive from an earlier draft of Beverly Cross’s script? Possibly, but more likely it is Foster’s invention; it’s typical of the expansion that appears throughout Clash of the Titans—and novelizations in general.

The lengthier dialogue scenes occur principally between Perseus and the old playwright Ammon, but their pacing feels adequate for a book. The cursed Calibos speaks much more than he does in the film, and Andromeda says to the monster’s face that she never loved him, even when he was still handsome—something she only explains in the film to Perseus at their pre-wedding feast. The feast contains an extra scene between Ammon and Cassiopeia, which I guess was either scripted and not shot, or else got cut from the final print.

However, scene-for-scene, Foster’s novel and the movie remain closely paired. In many places, Foster’s paragraphing and chapter breaks reflect the exact way the movie is cut, such as how the fight in the swamp between Perseus and Calibos abruptly ends with its results left inconclusive—until the middle of the next scene/chapter, when Perseus enters the temple of Thetis in Joppa to hurl Calibos’s hand onto the steps. I have to assume that this scene was already down on film with the exception of the stop-motion Calibos effects when Foster was writing.

But two sequences in the novelization were definitely written before Harryhausen completed the effects, because they represent older storyboard ideas rejected before the miniatures went before the cameras. This is where reading a novelization gets interesting, giving a dramatic presentation of what might have been.

The two scenes come back-to-back. First is the attack of “Dioskilos,” a two-headed wolf unnamed in the film’s dialogue but given a credit in the end titles. Early conceptions had this creature as Cerebus, the three-headed guardian dog of Hades, but three heads were too unwieldy to create an effective armatured model. Foster wrote his version after the change to Dioskilos, but his battle between the four warriors and the bicephalic wolf is more violent and gory than the film’s: the warrior Menas gets brutally ripped opened and partially devoured (on screen he seems to die through implication), and Perseus shears off one of Dioskilos’s heads before slaying it. Harryhausen eliminated these ideas out of concern for making the scene too gruesome, and because the decapitation was too similar to the adjacent Medusa scene. In the book, a chain holds Dioskilos to the sanctuary entrance, which reduces the scene’s tension. The snake wrapped around the sword that delays Perseus from joining the action was apparently also a later invention, since Perseus leaps right into the fight in the book. Foster writes the sequence with tremendous energy, making it feel much longer than screen version, but the filmmakers were correct to have toned it down—and to let Dioskilos off the leash.

Then there’s the Medusa confrontation, possibly the best work Harryhausen ever achieved. Appropriately, it’s also Foster’s best-written scene, showing that he had a good idea of the flickering-flame and dancing-shadows atmosphere of the sequence. But the novel’s differences are intriguing, and they all come from Harryhausen’s early ideas and storyboards. Medusa wears an upper “wrap” on her torso, instead of going bare-chested (with discretely hidden nipples). She scratches her arrow tips across her body to taint them with her poison blood—a great concept on the page, but perhaps a detail unneeded in the movie. The spilling of Medusa’s caustic blood causes the entire temple to collapse as Perseus escapes from it, which budget concerns must have cut—and Perseus’s slow emerging from the temple with the Gorgon’s head in his hand is the best non-effects moment in the movie, so I won’t argue. Most surprising about the novel’s scene is that Perseus decapitates Medusa with a Frisbee! Well, not a Frisbee, actually . . . a damaged, serrated shield he picks up and flings like a discus, making himself into the Bronze Age predecessor of Oddjob in Goldfinger. The filmmakers’ idea was that this gimmick might keep the scene from getting too violent by distancing Perseus from the killing, but “I can’t believe we even considered this over the sword,” Harryhausen wrote years later. Me neither. The novelization shows how silly this is, since it comes out of nowhere and undercuts the suspense. The film’s replacement—Perseus waiting until Medusa slithers beside his column, and then swinging his blade at the key moment—is a masterpiece of tension.

Novelizations tend to feel rushed in their finales, since pacing in a film requires a different speed for the final third than is normally comfortable for a novel, and Foster squeezes in an enormous amount of screen-time into his last three chapters: Medusa/the scorpions/Calibos’s death/releasing Pegasus/the Kraken/resolution. Foster’s writing is leisurely and sometimes beautiful for most of the book’s length, but with the exception of Medusa he gets stylistically choppier in the final sixty pages.

As entertaining as the novel of Clash of the Titans sometimes is, it still has barely a tenth of the magic of the film. I can’t blame Foster for this; it’s the fault of the novelization form combined with a superb movie. Film struggles to capture the written beauty and emotional immediacy of great novels, and we should expect a similar struggle to occur in the opposite direction—especially for a film so dependent on fantasy visuals. Foster writes well, but even the finest masterpiece of descriptive prose cannot capture the otherworldly awe of a Ray Harryhausen animated creature. For fans of Clash of the Titans, the novelization provides a minor supplemental experience, a peek at some strange earlier ideas (seriously, a freakin’ Frisbee), and an explanation for why Bubo the mechanical owl doesn’t accompany Perseus to the Isle of the Dead (“. . . apparently, his life force is not as flexible as our own. That which drives him would stop if he were to go that close to the underworld.”)

I ended this review with Bubo the Owl. I’m proud of that.

Right after I posted this article, I decided to write to Alan Dean Foster through his website to see if he had any comments on writing the novelization. Mr. Foster, showing himself to be a very generous and great guy, wrote back to me only a few hours later. Here is his complete letter:

Hi Ryan;

A nice and well-written piece. Rather than have to register and log in on the website in order to comment, I’ll place my comments here and you can reposition them where and as you prefer on the Gate page.

All of us grew up on Ray Harryhausen. I can’t count the number of times I saw the 7th Voyage of Sinbad . . . initially in a drive-in theater. So the opportunity to novelize one of his films was a particular delight.

As Ryan Harvey notes, there were a lot of changes in story and visuals while the film was finishing up. These are, naturally, the bane of the writer doing the book version of a film. They’re even more hand-wringing to the publisher, who is on a deadline for the book’s release. As Ryan notes in his article, the mythology in the film is hardly canon. But that never seemed to bother Harryhausen. What intrigued him were the potential visuals. His long-time producer Charlie Schneer confirmed this for me when we sat down for a discussion about the film prior to my getting to work on the book. “He’s not writing a text . . . he’s making a movie”, Charlie told me.

I thought the structure awkward, with jumping back and forth from the gods on Olympus to “real” life down on Earth. I always felt that way about everything from Homer to Herakles. If the gods can interfere in human existence any time they like, then what’s the point of trying to beat the odds? But since it was all about the visuals. . . .

There are contemporary analogues to this film-making approach that I need not point out.

I once asked Charlie why Ray didn’t do Lovecraft. Nowadays when Guillermo del Toro or whoever gets there first does HPL, it will all be CGI, but back then Ray was the only one who could have possibly done justice to Lovecraft’s visions. “All he wants to do is Greek mythology,” Charlie told me, in a tone that suggested that he personally was maybe just a little bit sick of Greek mythology and would have been delighted to essay something else.

A cinematic opportunity missed.

I hope this is useful to you, Ryan, and thanks for the kind words in the article regarding my work. As I recall, I had 3-4 weeks to do the book.

Regards,

Alan F

[…] For those of you interested, I’ve also reviewed the novelization of the original movie. […]

[…] may not believe this, based on other things I’ve written at this site, but I walked into my local movie theater showing the re-make of Clash […]

[…] the majority from Alan Dean Foster because Alan Dean Foster rocks (he even responded to my review of his Clash of the Titans novelization). But with Tarzan and the Valley of Gold I found myself for […]