Howard’s Forgotten Redhead: Dark Agnes

It’s strange that Robert E. Howard’s most famous female character is one he didn’t actually create: Red Sonja, the work of comic book writer Roy Thomas and artist Barry Windsor-Smith, based on the historic adventuress Red Sonya from the story “The Shadow of the Vulture.” Red Sonja has been erroneously credited to Howard for years; even the movie Red Sonja lists him as the creator on the main credits.

It’s strange that Robert E. Howard’s most famous female character is one he didn’t actually create: Red Sonja, the work of comic book writer Roy Thomas and artist Barry Windsor-Smith, based on the historic adventuress Red Sonya from the story “The Shadow of the Vulture.” Red Sonja has been erroneously credited to Howard for years; even the movie Red Sonja lists him as the creator on the main credits.

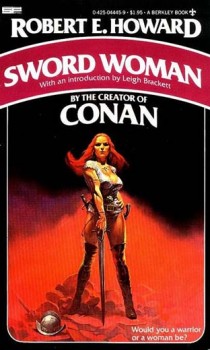

This accidental attribution might explain the scant attention given to a fierce, red-haired, sword-swinging woman that Howard did create: Dark Agnes of Chastillon, sometimes called Agnes de le Fere. She appears in two stories and a fragment, and if Howard had sold the stories during his lifetime he might have written far more about her. She’s much-neglected in discussions of the author, and none of her stories have been in print since Ace’s 1986 printing of Sword Woman, which was first published by Zebra in 1977 and then re-printed by Berkley in 1979.

Another reason for the general obscurity of the abbreviated Dark Agnes cycle is that the stories are lesser pieces that feel rough alongside Howard’s classics. But their content is worth examining to see the author exploring the first-person female point of view. Detractors who consider Robert E. Howard—and sword-and-sorcery in general—misogynistic will discover a genuine surprise in Dark Agnes.

Howard wrote the Agnes stories contemporaneously with C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry stories, and it’s tempting to compare the two and wonder if they had any influence each other. The first Jirel story, “Black God’s Kiss,” was already in print when Howard wrote “Sword Woman.” Howard sent “Sword Woman” to C. L. Moore, and expressed appreciation of it in a January 1935 letter. But, as Leigh Brackett says in her 1977 introduction to the collection of Dark Agnes stories, “at this late date it is impossible to say which character was first conceived, or whether indeed there was any connection between them at all.” There is little in common between the characters aside from their red hair and their defiant spirit. The Jirel stories are strange, dark fantasies in which the heroine engages in emotional battles instead of physical ones. The Dark Agnes stories are historical swashbucklers with copious action and the heroine showing she’s better than any man with a sword . . . indeed, she seems born to the blade.

“Sword Woman,” first published in 1975 in REH: Lone Star Fictioneer No. 2, is Dark Agnes’s origin story. The setting is France, and based on the weaponry and mention that the Holy Roman Emperor is “Charles of Germany,” the time period is probably during the reign of Emperor Charles V, 1519–1556. Anges de Chastillon is a peasant girl, the daughter of an illegitimate son of the Duke of Chatillon. Her father, a former mercenary of the Free Companions, is a lout about to give Agnes into a hateful marriage. Agnes takes a desperate—and perfectly Howardian—way out: she stabs her groom to death at the altar and dashes off into the woods. The story never quite retains this level of gutsy shock again, but Howard makes Agnes into a tough figure the equal of any of his male heroes. She meets with the gentleman Etienne Villiers on the road, but when she finds out that he plans to sell her off to a brothel, she beats him to the edge of death. However, when Agnes discovers she has accidentally betrayed Etienne’s identity to the servants of the Duke of Alencon, who wants Etienne dead because he knows of the Duke’s plotting against the French Throne, she decides to save him. After she meets Guiscard de Clisson of the Free Companions, Agnes convinces him to let her join his company. But an ambush on the road by Duke of Alencon’s killers will throw Agnes into a partnership—although not a romance—with the hunted Etienne.

“Sword Woman” reads as set-up, perhaps a necessary piece for Howard to get the character ready for more developed stories. However, it ends up as the most interesting and polished of the three stories. The plot is a trifle and ends abruptly, but most of the focus is on Agnes as a character—and she’s riveting. That Howard chose to deny Anges a romantic foil, or to have her finally “give herself” to a stronger man, is remarkable for the time period. Her speech to Guiscard, when he first rejects her offer to join the Free Companions, is a classic Robert E. Howard Declaration of Principles:

“Ever the man in men!” I said between my teeth. “Let a woman know her proper place: let her milk and spin and sew and bake and bear children, not look beyond her threshold or the command of her lord and master! Bah! I spit on you all! There is no man alive who can face me with weapons and live, and before I die, I’ll prove it to the world. Women! Cows! Slaves! Whimpering, cringing serfs, crouching to blows, revenging themselves by—taking their own lives, as my sister urged me to do. Ha! You deny me a place among men? By God I’ll live as I please and die as God wills, but if I’m not fit to be a man’s comrade, at least I’ll be no man’s mistress. So go ye to hell, Guiscard de Clisson, and may the devil tear your heart!”

Howard isn’t subtle, but his passion is undeniable. No wonder C. L. Moore liked the story so much.

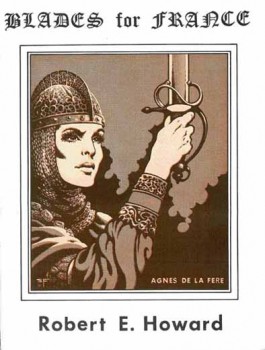

“Blades for France” was first published in 1975 in a limited edition chapbook from George Hamilton. It follows closely on events in “Sword Woman,” with Agnes and Etienne still paired up, and seeking a way to Italy while Renault d’Valence chases them because of they know too much about his part in Guiscard’s death. Through an accidental encounter, a disguised Agnes falls in with d’Valence’s men and uncovers a plot involving French royalty and English pirates. The brief story ends up with too much plot for its own good, although the historical “guest stars” who pop up at the finale add a nice touch, and the action scenes have the usual Howard snap. Agnes remains tough and unfazeable, although her personality isn’t at the forefront as much as in “Sword Woman.”

“Blades for France” was first published in 1975 in a limited edition chapbook from George Hamilton. It follows closely on events in “Sword Woman,” with Agnes and Etienne still paired up, and seeking a way to Italy while Renault d’Valence chases them because of they know too much about his part in Guiscard’s death. Through an accidental encounter, a disguised Agnes falls in with d’Valence’s men and uncovers a plot involving French royalty and English pirates. The brief story ends up with too much plot for its own good, although the historical “guest stars” who pop up at the finale add a nice touch, and the action scenes have the usual Howard snap. Agnes remains tough and unfazeable, although her personality isn’t at the forefront as much as in “Sword Woman.”

Howard left the third Agnes story, “Mistress of Death,” unfinished. Gerald W. Page completed it, based on Howard’s surviving synopsis, and it first appeared in print in the January–February 1971 issue of Witchcraft and Sorcery (a magazine that Page owned), making it the earliest of the Agnes stories available to the public. It’s the only story with fantasy elements: Agnes faces an undead sorcerer in the city of Chatres. She has a new partner in this venture, a Scotsman named John Stuart whom she runs into during a fight with killers in an alley. The story finishes in a good horror-filled encounter in the catacombs of the necromancer Costranno, and if this is the work of Page, it’s an excellent imitation of Howard’s style. But Agnes does a bit of the “wilting damsel” routine at the end, which goes against her established fearlessness, and I suspect that this is also Page’s doing.

Roy Thomas adapted “Mistress of Death” into the Conan story “Curse of the Undead Man” for the first issue of Savage Sword of Conan, with art by John Buscema and Pablo Marcos. John Stuart becomes Conan, and Dark Agnes becomes, of course, Red Sonja. (Actually, there is some intermingling of the original characters’ functions.)

Because the Dark Agnes stories do not fill enough space for a single volume, the collection Sword Woman includes two unrelated fragments: “The King’s Service” and “Shadow of the Hun.” The first was intended as a novel, but the Howard only got through a prologue and two chapters. It shows significant promise for a longer story that combines Howard’s love of the Celtic hero with his favored plots about exotic lost civilizations and political intrigue. The fragment begins with a ship of Saxon warriors finishing an astonishing journey around the tip of Africa to the glorious Indian city of Nagdragore. Their Briton prisoner and the intended hero of the story, Donn Othna, is able to speak in Latin to the Greek rajah of the city, Constantius. The rajah wants the Northlanders to help him against factions that are trying to ruin him. The aborted piece concludes after an exciting fight between Donn Othna and a muscular strangler sent to murder the rajah. Just as things were getting exciting. . . .

“The Shadow of the Hun” is a strange stub that seems as if Howard was flailing in several different directions, trying to find the path that worked the best, and sometimes writing passages that read more like notes to himself. The hero is Turlogh Dubh O’Brien, the Gael who appears in two of Howard’s best stores, “The Dark Man” and “The Gods of Bal-Sagoth.” A prologue begins with Turlogh and two companions riding across the ocean, then an abrupt leap back in time takes the reader to Turlogh rescuing a Slavic youth from attackers on the Turkish steppes. Turlogh joins the boys tribe. Another flashback within this story explains how Turlogh got so deep into Central Asia. With so many ideas leaping around, it seems that even Howard didn’t know to go with it and abandoned the piece.

With the current crop of excellent Howard reprints, it’s strange that Dark Agnes has not made the leap into the thick anthologies of the author’s stories. Although they do not reach the level of quality of Howard’s great works, the subject matter makes them worthy of reappraisal.

Del Rey are supposed to publish a ‘Dark Agnes’ collection (padded with other historicals) in 2011.

‘El Borak’ collection is due out in 2010.

[…] Dark Agnes: http://www.blackgate.com/2009/12/29/howard%E2%80%99s-forgotten-redhead-dark-agnes/ […]