My Fantasia Festival, Day 11 (part 2): To Be Takei and The Creeping Garden

I saw two movies in the late afternoon and evening of the Sunday before last (the 27th). Both were documentaries. You’d think that the first one would have had the more obvious science-fiction content, being a biography of an actor who rose to fame playing a character on perhaps the best-known science-fiction TV show of all time — while the second film was an in-depth examination of what sounds like the most mundane substance in the world. This did not turn out to be the case. The old saying about truth, fiction, and strangeness applies.

I saw two movies in the late afternoon and evening of the Sunday before last (the 27th). Both were documentaries. You’d think that the first one would have had the more obvious science-fiction content, being a biography of an actor who rose to fame playing a character on perhaps the best-known science-fiction TV show of all time — while the second film was an in-depth examination of what sounds like the most mundane substance in the world. This did not turn out to be the case. The old saying about truth, fiction, and strangeness applies.

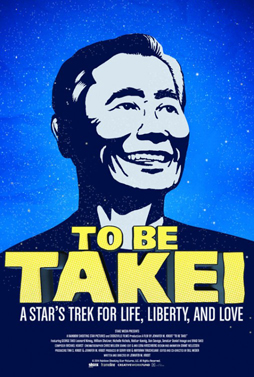

At 5:20 I saw To Be Takei in a packed, and fairly raucous, De Sève Theatre. It’s much as it sounds: the story of George Takei, the original Star Trek’s Mister Sulu. But Trek is only a part of his life and of the movie, which ranges from Takei’s childhood in a World War Two internment camp to his experience as a gay man growing up and forming a career to his later political experiences to his current status as a social media celebrity.

Then at 9:45, I saw the world premiere of The Creeping Garden, a documentary about slime mould. Which, it turns out, is a deeply strange thing, not plant nor animal nor fungi, a creature that occasionally demonstrates something a lot like intelligence. There’s an almost Lovecraftian air to the movie, which ends up exploring odd byways of cinema history, art projects, and ‘alternative computing.’ There’s cutting-edge science in this documentary, if not actual mad scientists.

But let me start with the earlier film (preceded, in this case, by 35mm trailers for two of the Star Trek movies, III and VI). To Be Takei was co-directed by Jennifer M. Kroot and Bill Weber. For the most part they remain offscreen; you occasionally hear a voice asking a question, but Takei and his husband Brad seem quite able to carry the cinematic conversation on their own. And indeed maybe more than George Takei himself, the relationship between the two men is the focus of the movie. You learn a lot about their marriage, and how they met, and how they support each other emotionally. How they care for each other. You see them together for important family events, notably when they scatter Brad’s mother’s ashes. The movie also describes Takei’s activism for gay marriage rights, and there may be a level on which the film in and of itself helps normalise the idea of two men married to each other — simply by depicting a supporting and loving marriage which has two husbands.

But let me start with the earlier film (preceded, in this case, by 35mm trailers for two of the Star Trek movies, III and VI). To Be Takei was co-directed by Jennifer M. Kroot and Bill Weber. For the most part they remain offscreen; you occasionally hear a voice asking a question, but Takei and his husband Brad seem quite able to carry the cinematic conversation on their own. And indeed maybe more than George Takei himself, the relationship between the two men is the focus of the movie. You learn a lot about their marriage, and how they met, and how they support each other emotionally. How they care for each other. You see them together for important family events, notably when they scatter Brad’s mother’s ashes. The movie also describes Takei’s activism for gay marriage rights, and there may be a level on which the film in and of itself helps normalise the idea of two men married to each other — simply by depicting a supporting and loving marriage which has two husbands.

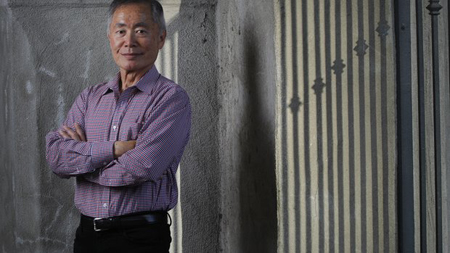

If the marriage anchors the documentary in the here-and-now, it also of course moves back to George Takei’s childhood and gives an overview of his life. The movie argues convincingly that he was shaped by his early experiences in the internment camps. There’s a montage of a speech he gives at public events giving the background of the camps and what happened to him and his family, but beyond that there’s considerable reflection by Takei himself and by his friends on how the camps affected him. The film shows us Takei as driven to achieve and relentlessly positive, and implies those characteristics were shaped by his reaction to the camps and the racism of the 1940s.

There’s also a considerable amount of screen time given to what it was like for Takei discovering he was gay in a society that really did not encourage such a discovery. That becomes an investigation of what it was like to live a closeted life for decades, and what prompted him to finally come out (Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2005 veto of a bill that would have allowed gays to marry). It examines his experiences alone and as part of a couple, and his worries about how his sexuality and coming out of the closet would affect his career.

There’s also a considerable amount of screen time given to what it was like for Takei discovering he was gay in a society that really did not encourage such a discovery. That becomes an investigation of what it was like to live a closeted life for decades, and what prompted him to finally come out (Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2005 veto of a bill that would have allowed gays to marry). It examines his experiences alone and as part of a couple, and his worries about how his sexuality and coming out of the closet would affect his career.

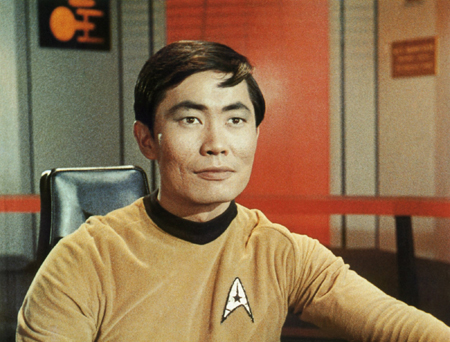

That career, of course, is what mainly led to the movie. It’s almost a paradox. Takei’s led a full, accomplished life, much of which was deeply affected by one TV role he played in the 1960s. It doesn’t denigrate his work to observe that he wasn’t at the centre of the Star Trek phenomenon — he wasn’t one of the primary creators, or one of the top-billed actors. He was an important part of the show, but not its core. Yet the success of Trek has affected his life (so far as the movie shows, for the better) and allowed him to gain visibility both for himself and for the causes that matter to him. So in discussing his life, Star Trek is both at the centre and outside it: it has a kind of gravitational pull, if you like, an effect that Takei contributed to but for which he was not primarily responsible. The movie finds a way to discuss Trek in the context of Takei’s life without overbalancing; without moving away from Takei by putting too much weight on the show.

It likely helps that Takei doesn’t seem at all conflicted over his Trek experience. He does mention that the original show is for him not unlike “baby pictures,” but Trek obviously mean a lot to him beyond the effect it’s had on so many people around the world. There’s a touching joy in the way he talks about Star Trek VI, and what it was like for him to start reading the script and see that Sulu was now a captain; and then to get to the end, and see that Sulu and his ship came in to save the day. There’s also charming glee in the way he insists that film was actually a “Captain Sulu” movie. (Takei’s also happy when he talks about his favourite episode, “The Naked Time,” when he got to get out from behind his console and swing a sword — originally written as a samurai sword, before Takei, a fan of Errol Flynn movies, suggested changing to the less-stereotypical rapier.)

It likely helps that Takei doesn’t seem at all conflicted over his Trek experience. He does mention that the original show is for him not unlike “baby pictures,” but Trek obviously mean a lot to him beyond the effect it’s had on so many people around the world. There’s a touching joy in the way he talks about Star Trek VI, and what it was like for him to start reading the script and see that Sulu was now a captain; and then to get to the end, and see that Sulu and his ship came in to save the day. There’s also charming glee in the way he insists that film was actually a “Captain Sulu” movie. (Takei’s also happy when he talks about his favourite episode, “The Naked Time,” when he got to get out from behind his console and swing a sword — originally written as a samurai sword, before Takei, a fan of Errol Flynn movies, suggested changing to the less-stereotypical rapier.)

Takei remembers having an oblique discussion with Gene Roddenberry about doing a Trek episode centred around homosexuality. Although the show was and is famous for the way it dealt with social issues, Roddenberry felt that the issue was too contentious, and Trek too low-rated, for gay issues to be brought forward on the show. The movie does an interesting job contrasting that with the fanzine culture that sprang up around Trek, and the slash fiction that developed out of that (and it is a distinctly surreal experience to see Leonard Nimoy discussing slash fanfiction). Takei also speaks about gayness with respect to the Trek ideal of IDIC, Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations, and how that ideal mattered to him.

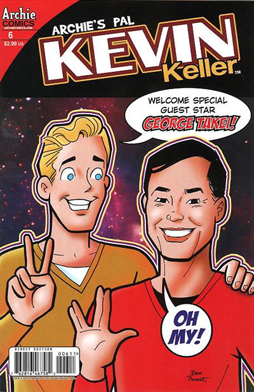

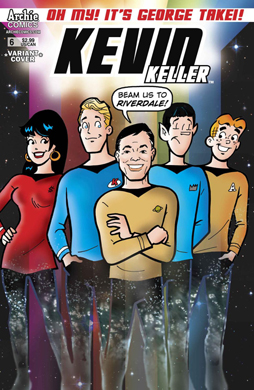

To Be Takei is a very funny movie. Takei himself has a tremendous sense of humour, and excellent comic timing and delivery. But the film also pushes past that humour to present the importance of the man. People like Dan Savage and John Cho (Sulu in the Trek reboot movies) talk about Takei as an icon. We see him at comics conventions, signing an Archie comic in which he guest stars.

To Be Takei is a very funny movie. Takei himself has a tremendous sense of humour, and excellent comic timing and delivery. But the film also pushes past that humour to present the importance of the man. People like Dan Savage and John Cho (Sulu in the Trek reboot movies) talk about Takei as an icon. We see him at comics conventions, signing an Archie comic in which he guest stars.

And at the same time it hints some darkness in his character. Brad Takei complains that George likes to tease people about putting on weight. We see George himself doing push-ups and sit-ups: after he kids Wil Wheaton about gaining weight, and the crestfallen Wheaton says something about Takei being in shape, he tells Wheaton “You’ve got to maintain!” That hint of competitiveness comes out in the movie’s discussion of Takei’s relationship (or lack of same) with William Shatner, lead actor and former captain. It’s clear that the rest of the original Trek cast have had their differences with Shatner, but it also seems that Takei feels it especially keenly. There’s an odd omission in the movie when it shows a clip of him at a roast of William Shatner bursting out “Fuck you and the horse you rode in on!” without noting that Shatner had, in fact, ridden in to the event on a horse. But the passion in Takei’s voice, after seeing him otherwise so composed throughout the film, is startling.

I noticed another omission that was perhaps more significant. The film discusses Takei’s career in the context of ethnically Asian actors in the American industry, from his first roles as dubbed voices in Godzilla movies through Trek and beyond. As a part of that Takei mentions some demeaning roles he took, in which he had to speak in an affected accent and generally play to ethnic steroetypes. And he talks about how conflicted he was about the roles, and the career pressures he felt. But elsewhere the movie shows Takei in an episode of The Twilight Zone, and doesn’t talk about the role he had therein: the son of a Japanese-American who betrayed the US to the Japanese. Never rerun in America due to protests, the episode imagined a kind of treason that never happened, but the fear of which led to the creation of the internment camps. So given how much the movie deals with Takei’s childhood in the camps, it seems like Takei’s choice to take the role and his feelings about the job might have been worth exploring a little further.

I noticed another omission that was perhaps more significant. The film discusses Takei’s career in the context of ethnically Asian actors in the American industry, from his first roles as dubbed voices in Godzilla movies through Trek and beyond. As a part of that Takei mentions some demeaning roles he took, in which he had to speak in an affected accent and generally play to ethnic steroetypes. And he talks about how conflicted he was about the roles, and the career pressures he felt. But elsewhere the movie shows Takei in an episode of The Twilight Zone, and doesn’t talk about the role he had therein: the son of a Japanese-American who betrayed the US to the Japanese. Never rerun in America due to protests, the episode imagined a kind of treason that never happened, but the fear of which led to the creation of the internment camps. So given how much the movie deals with Takei’s childhood in the camps, it seems like Takei’s choice to take the role and his feelings about the job might have been worth exploring a little further.

Still, that’s something of a quibble. Overall To Be Takei is a strong biography that shows what is significant about its lead — what there is to him beyond Star Trek. It’s well-structured, and builds character very nicely, as well as the relationship between characters. It hints at just enough darkness in its subject to give texture and the sense of a real, well-rounded person, while also establishing his significant virtues. It’s a fun documentary that deals with very serious topics, and ultimately makes the audience feel almost as upbeat as Takei himself.

Still, that’s something of a quibble. Overall To Be Takei is a strong biography that shows what is significant about its lead — what there is to him beyond Star Trek. It’s well-structured, and builds character very nicely, as well as the relationship between characters. It hints at just enough darkness in its subject to give texture and the sense of a real, well-rounded person, while also establishing his significant virtues. It’s a fun documentary that deals with very serious topics, and ultimately makes the audience feel almost as upbeat as Takei himself.

The Creeping Garden was an entirely different creature. Co-directed by Tim Grabham and Jasper Sharp, it shines a light on plasmodial slime mould. And it’s utterly, utterly fascinating. It is a strange movie, and very like something a New Weird fantasist might imagine. But it’s also understated, built mainly out of interviews with people investigating the peculiar nature of slime moulds. There’s a directness to this documentary, an intense seriousness that may in part come from a low budget but which in any event works with the otherwise surreal subject.

The one striking photographic technique that is used often is time-lapse photography, showing the slow-moving slime moulds sending out tendrils seeking food. Moulds like carbohydrates, so people that work with them use oat cakes and similar things as rewards. We see moulds ‘navigating’ a maze to find their food, and sprawling across maps to locate foodstuffs placed on the sites of major cities — it turns out that the moulds replicate roadways surprisingly accurately, so that on a map of Italy they recreated the Roman road network, while on a map of Germany they recreated the split between east and west. This sort of thing leads many to ascribe a rudimentary intelligence to slime moulds, if of an utterly inhuman kind.

There’s an uncanny feel to the documentary, which isn’t afraid to build atmosphere with long shots of the natural world. You can almost smell the damp and decay of the woodlands where an “amateur mycologist” seeks out the mould in its home terrain. An electronic soundtrack from Jim O’Rourke (former member of Sonic Youth) perfectly complements the visuals. There’s no psychedelia here, only an investigation of the nature of the moulds which proves mind-altering all on its own.

There’s an uncanny feel to the documentary, which isn’t afraid to build atmosphere with long shots of the natural world. You can almost smell the damp and decay of the woodlands where an “amateur mycologist” seeks out the mould in its home terrain. An electronic soundtrack from Jim O’Rourke (former member of Sonic Youth) perfectly complements the visuals. There’s no psychedelia here, only an investigation of the nature of the moulds which proves mind-altering all on its own.

The filmmakers interview artist Heather Barnett, who uses science in her art (one of her non-mould projects is wallpaper printed with individualised cell patterns, so “you decorate your interior space with your interior space”) and uses moulds specifically as an element that can be manipulated to a degree but not absolutely controlled. A man at a “fungarium” talks about the moulds as “black sheep of the mycological world.” A historian shows early magic lantern slides with scientific diagrams of the moulds; magic lanterns, as he points out, were used by the Victorians for education and entertainment, and were a kind of proto-cinema. Slime moulds, then, are linked with the prehistory of film.

The slime moulds have significance in a number of ways, starting with the modelling of decision making; Barnett is shown conducting a ‘human slime mould’ experiment, in which volunteers are roped together and given a set of rules mimicking mould behaviour under which they have to expand their links to reach a goal. The way moulds grow apparently has applications in how things like fire escape routes may be planned, and how non-hierarchical networks may be formed. The movie spends considerable time with a scientist at the International Center of Unconventional Computing, who discusses the importance of moulds in biological computing. He plays music derived from the electrical impulses of moulds in various states, demonstrating the ‘mood’ of the moulds — which also may be seen in a detailed robotic ‘head’ linked up to a mould colony.

The documentary’s perfectly clear at all times, but also dizzying simply due to the ideas it presents and its willingness to follow those ideas to very strange places. Its structure is clear and thankfully not entirely rational: it moves deeper and deeper into the possibilities people have found in the moulds. If you didn’t know that it was all quite true (and I have browsed around some links confirming what I saw in the film) you’d swear it was a some kind of science-fictional mockumentary. But the mould is very real, and truth very much stranger than our fictions.

The documentary’s perfectly clear at all times, but also dizzying simply due to the ideas it presents and its willingness to follow those ideas to very strange places. Its structure is clear and thankfully not entirely rational: it moves deeper and deeper into the possibilities people have found in the moulds. If you didn’t know that it was all quite true (and I have browsed around some links confirming what I saw in the film) you’d swear it was a some kind of science-fictional mockumentary. But the mould is very real, and truth very much stranger than our fictions.

A question-and-answer session with the directors followed the screening (as usual, the following is reconstructed from my notes). The filmmakers hadn’t had the chance before that evening to see the movie on a big screen or with an audience, and were obviously pleased with the sold-out showing. Jasper Sharp, who has written books about Japanese cinema and co-edits the Midnight Eye website, recalled that it had been three years that he had been working on the movie with his “partner in slime” Tim Grabham — an artist, animator, and filmmaker. They talked about how the movie began to come together as they worked out that it had to focus on the people involved in trying to understand the moulds.

In response to questions, they discussed the film’s link of the technical and the aesthetic. Grabham mentioned that they had much more material about the scientist at the Centre For Unconventional Computing, enough to make a whole film around him. Sharp said that they could’ve made a 20-hour film with all the material they found. Asked if they ever felt as if they were going “down the rabbit hole” in the making of the film, Sharp said yes, at once, “but that’s a good place to be, I think.” Grabham talked about working with the mould, which would grow at unpredictable intervals, and how the style found itself through what their two-person team was able to do. He did mention an influence from 70s science-fiction films.

In response to questions, they discussed the film’s link of the technical and the aesthetic. Grabham mentioned that they had much more material about the scientist at the Centre For Unconventional Computing, enough to make a whole film around him. Sharp said that they could’ve made a 20-hour film with all the material they found. Asked if they ever felt as if they were going “down the rabbit hole” in the making of the film, Sharp said yes, at once, “but that’s a good place to be, I think.” Grabham talked about working with the mould, which would grow at unpredictable intervals, and how the style found itself through what their two-person team was able to do. He did mention an influence from 70s science-fiction films.

Asked whether they believed the moulds were intelligent, the filmmakers were unwilling to say either yes or no. Grabham said that while he wasn’t sure, Barnett was convinced they were. Sharp pointed out that the moulds had been around for 40 million years, which on its own said something. This is a creature with, as he said, an unknown functionality. It seems in fact to have none — no specific ecological niche, no irreplaceable link on the food chain. It was an appropriate note to end on, an oddly evocative set of facts that only deepened the low-key sense of mystery. In examining a common everyday substance, Grabham and Sharp had brought out a real sense of wonder. Thoughtful and surprising, The Creeping Garden succeeds in making the world approximate the condition of science fiction.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Fascinating review, Matthew. I came for Takei, and ended up equally fascinated by the slime moulds. Sounds like a great double feature!

Thanks! Yeah, these were two really good films to see together. They balanced nicely, somehow.