Pre-Twilight Zone Birthday Notes

I’m going to be brief today, something that I rarely am. I’ve planned a massive retrospective of The Twilight Zone’s first season in honor of the show’s Fiftieth (yes, Fiftieth) Anniversary, which occurs on October 2nd. However, I didn’t want to throw it out before October 2nd, and as that day falls on a Friday, I wouldn’t be able to post on that exact date. Oh, and I haven’t finished the essay yet either, which is about the best excuse there is. So I’ve ended up with a topic hole for today. And that’s why I’m rambling about what you’re not reading about.

To compensate, I’m offering you a pre-Twilight Zone warm-up: links to reviews that I’ve done for various first season episodes. I spent a good part of the summer going over the the program’s first season and getting to grips with how it developed, and I’ll share those collected observations next week after the show has had time to blow out its candles. For right now, here’s the minutiae on selected episodes. Bring an extra pair of prescription glasses.

#1 “Where Is Everybody?”

#5 “Walking Distance”

#8 “Time Enough at Last”

#11 “And When the Sky Was Opened”

#13 “The Four of Us Are Dying”

#16 “The Hitch-Hiker”

#18 “The Last Flight”

#22 “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” (my favorite of the season)

#24 “Long Live Walter Jameson”

#27 “The Big Tall Wish”

#29 “Nightmare as a Child”

#30 “A Stop at Willoughby”

#34 “The After Hours”

#36 “A World of His Own”

I’m a sucker for retrospective anthologies. And F&SF is one of my favorite magazines — and has been since I first discovered tattered copies in the tiny library of Rockcliffe Air Force base in Ottawa, Canada, in the late 70s. Editor Gordon van Gelder has assembled an imposing, 470-page collection spanning more than five decades, starting with Alfred Bester’s “Of Time and Third Avenue” (1951) and ending with Ted Chiang’s “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” (2007).

I’m a sucker for retrospective anthologies. And F&SF is one of my favorite magazines — and has been since I first discovered tattered copies in the tiny library of Rockcliffe Air Force base in Ottawa, Canada, in the late 70s. Editor Gordon van Gelder has assembled an imposing, 470-page collection spanning more than five decades, starting with Alfred Bester’s “Of Time and Third Avenue” (1951) and ending with Ted Chiang’s “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” (2007). I don’t often get the opportunity to encounter true works of ancient artwork, those anonymous pieces of bronze and stone and gold that appear reproduced in textbooks, volumes of history, and museum brochures. Living on the western edge of the New World means I have a lack of local access to them, and when I’m in the Old World, I’m usually among the artworks of the early modern masters, who painted onto canvas their dreams of the ancients. Not that such art isn’t wonderful, but I’m a classicist deep down in my cerebellum, and I don’t get to engage with the genuinely ancient as often I would like.

I don’t often get the opportunity to encounter true works of ancient artwork, those anonymous pieces of bronze and stone and gold that appear reproduced in textbooks, volumes of history, and museum brochures. Living on the western edge of the New World means I have a lack of local access to them, and when I’m in the Old World, I’m usually among the artworks of the early modern masters, who painted onto canvas their dreams of the ancients. Not that such art isn’t wonderful, but I’m a classicist deep down in my cerebellum, and I don’t get to engage with the genuinely ancient as often I would like. The much anticipated — and feared — “reimagining” of Patrick McGoohan’s classic cult TV series The Prisoner is scheduled for release on AMC in November. One good sign is that Ian McKellen is cast as Number Two (a role which, unlike the original series, will not revolve among multiple actors) and is (like the original) of fixed duration. James Caviezal is Number 6 and there are some interesting parallels here. Caviezal played Jesus in Mel Gibson’s (who was rumored to be a candidate for Number 6 in the various movie proposals over the year) The Passion of the Christ, controversial for its brutal, some would say sado-masochistic, portrayal of the Gospel stories. Like McGoohan, Caviezal is an observant Cathloic. Caviezal has made public stands on such issues as stem cell research and it is not inconceivable this might have affected his career in an industry that for the most part tilts left; McGoohan reportedly turned down the role of James Bond for moral reasons and insisted in his contract that he would not kiss women on-screen, particularly ironic given that The Prisoner was embraced by the sexual liberation advocates of the Sixties counter-culture for the program’s non-conformist ethos.

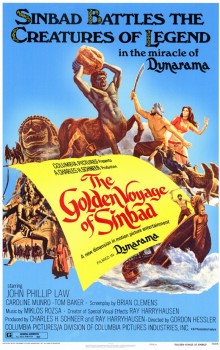

The much anticipated — and feared — “reimagining” of Patrick McGoohan’s classic cult TV series The Prisoner is scheduled for release on AMC in November. One good sign is that Ian McKellen is cast as Number Two (a role which, unlike the original series, will not revolve among multiple actors) and is (like the original) of fixed duration. James Caviezal is Number 6 and there are some interesting parallels here. Caviezal played Jesus in Mel Gibson’s (who was rumored to be a candidate for Number 6 in the various movie proposals over the year) The Passion of the Christ, controversial for its brutal, some would say sado-masochistic, portrayal of the Gospel stories. Like McGoohan, Caviezal is an observant Cathloic. Caviezal has made public stands on such issues as stem cell research and it is not inconceivable this might have affected his career in an industry that for the most part tilts left; McGoohan reportedly turned down the role of James Bond for moral reasons and insisted in his contract that he would not kiss women on-screen, particularly ironic given that The Prisoner was embraced by the sexual liberation advocates of the Sixties counter-culture for the program’s non-conformist ethos. The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974)

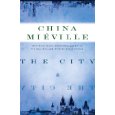

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974) Intriguing premise — and something quite different from his previous work, which is always good to see in a favorite novelist — where two presumably East European cities somehow physically co-exist, with the inhabitants following strict protocols to avoid one another whenever their separate realities intersect. Grossman would be happy that it has compelling plotting; however, as a “police procedural,” Miéville doesn’t quite play fair. Part of the game in these kind of things is to at least give the reader a chance of figuring out the mystery of “whodunnit,” which I doubt anyone would be able to, although I’m guessing this isn’t Miéville’s concern here. I think he’s aiming at something more metaphorical along the lines of the existential spaces we all tread among the various realms of social interaction. Nonetheless, the unfolding of the mystery struck me as a little forced. Potentially, this could be the start of a series.

Intriguing premise — and something quite different from his previous work, which is always good to see in a favorite novelist — where two presumably East European cities somehow physically co-exist, with the inhabitants following strict protocols to avoid one another whenever their separate realities intersect. Grossman would be happy that it has compelling plotting; however, as a “police procedural,” Miéville doesn’t quite play fair. Part of the game in these kind of things is to at least give the reader a chance of figuring out the mystery of “whodunnit,” which I doubt anyone would be able to, although I’m guessing this isn’t Miéville’s concern here. I think he’s aiming at something more metaphorical along the lines of the existential spaces we all tread among the various realms of social interaction. Nonetheless, the unfolding of the mystery struck me as a little forced. Potentially, this could be the start of a series.

Incredible Adventures

Incredible Adventures