The “Other” Harryhausen: The 3 Worlds of Gulliver

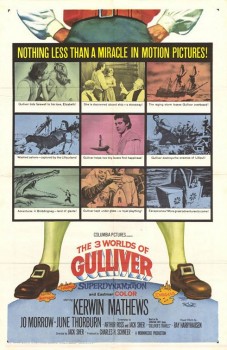

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960)

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960)

Directed by Jack Sher. Starring Kerwin Mathews, June Thorburn, Grégoire Aslan, Basil Sydney, Jo Morrow, Sherri Alberoni, Peter Bull.

First there was the Dynamation spectacle of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. Then there was Mysterious Island. Then the miracle of Jason and the Argonauts, and… wait, I seem to have skipped one. Oh yes, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver, made right after Sinbad. Now how did that one slip away?

Among the “Core Ten” Harryhausen films, the ten color fantasy and period science-fiction pictures he made between 1958 and his retirement in 1981 (all but one produced with Charles H. Schneer), The 3 Worlds of Gulliver gets the least amount of love now. For most of the 1980s, it was probably the unfortunate The Valley of Gwangi that suffered the most neglect, but that was because of its unavailability on video. (The weird name wasn’t helping it either; it certainly wasn’t the filmmakers’ first choice for the title.) Today, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver has turned into something of “the other movie” in the list of Harryhausen classics, even though it came out in 1960 fresh after the smash global success of The 7th Voyage Sinbad and featured that movie’s star, Kerwin Mathews, and its composer, Bernard Herrmann. In fact, Herrmann’s score is well-loved and appreciated among music fans through multiple re-recordings, but those same music lovers often haven’t watched the movie that inspired the music.

As a Harryhausen fanatic, even I’m guilty of ignoring The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. Although I saw it a number of times as a child and then as an adult enthusiast of fantasy and visual effects, it’s the only Harryhausen film I didn’t own on DVD. I decided it was time for a re-evaluation of the “missing” film of the catalogue, so I at last purchased the disc and took a good look at Ray Harryhausen’s visit to the Jonathan Swift classic.

I’ll step back for a moment and let Ray say something about his own opinion of the film. From his autobiography, An Animated Life:

When I see the film today, I find it entertaining, but I have to say it is not one of our best. It retains some elements of the Swift books and maintains a good, eighteenth-century feel, but the pace is not right, and because of this the film as a whole suffers. Although I am generally pleased with the overall effects, I miss the creature set-pieces—another reason it lacks that all important magic quality that any fantasy film needs.

Perhaps I need not continue with my own review, because the Great Man himself has zeroed in on my feelings about The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. It’s enjoyable — definitely above the more tatty attempts at children’s fantasy that were coming out at the time — and maintains a touch more Swiftian satire than you might imagine considering its target younger audience. But it never gels into a whole like some of Harryhausen’s other classics, especially the astonishing The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, my choice for the best work he and Charles H. Schneer ever did. The first half of the film, where Gulliver plays giant to the diminutive Lilliputians, manages to engage with its oriental court trappings and sharp-tongued dialogue, but the story starts to drag once Gulliver shifts over to imprisonment among the enormous Brobdingnagians and their dull medieval dross. This is probably the pace problem that Harryhausen noticed years later; the film simply feels done a half an hour before the words “The End” appear on screen.

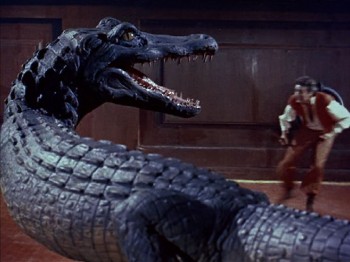

Most damaging, however, is the movie’s lack of stop-motion marvels. There are only two: a briefly spotted squirrel and a giant alligator. Because we associate Ray Harryhausen with his monsters, dinosaurs, and living skeletons, the general absence of these wonder creatures in The 3 Worlds of Gulliver can’t help but disappoint viewers today.

Most damaging, however, is the movie’s lack of stop-motion marvels. There are only two: a briefly spotted squirrel and a giant alligator. Because we associate Ray Harryhausen with his monsters, dinosaurs, and living skeletons, the general absence of these wonder creatures in The 3 Worlds of Gulliver can’t help but disappoint viewers today.

Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels has confounded adaptation for centuries. It looks like a children’s adventure story on the surface, but it’s really a vicious satire on humanity. Consequently, nobody seems to know what to do with it on film or television. Most versions use only the first two parts of the episodic novel: Lemuel Gulliver’s adventures among the tiny and petty Lilliputians (a mockery of the court of King George I) and then with the enormous but kindly Brobdingnagians. Some versions only use the Lilliputians. The visit to the floating island of Laputa and the marooning in the land of the intelligent horses called the Houyhnhnms usually don’t get mentioned, and that’s the case with The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. Common with many other film and television versions, the movie largely lays aside Swift’s misanthropy to focus on the fantasy elements that appeal to children.

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver is the only script of the Harryhausen-Schneer canon that they did not develop in-house at Morningside Productions. Writers Arthur Ross and Jack Sher penned the script for a planned musical with Danny Kaye, but after Universal dropped the option, Columbia picked it up for Morningside. Two brief and unmemorable musical numbers survived into the film, but the writers re-worked the screenplay to fit the style of a straightforward fantasy. Sher also took the helm as director.

Some satire creeps into the finished product, although the script handles it lightly and most of it occurs in the Lilliputian segment. The Lilliputians are again petty realpolitik twerps, and are at war with the neighboring country over something as silly as what end of an egg to crack open first. The giants of Brobdingnag are completely different from their literary source, portrayed as trapped in a medieval mindset. They eventually condemn Gulliver as a witch because he can practice effective medicine. Elizabeth, Gulliver’s wife, joins him on the Borbdingnagian adventure. This romance element further softens the satire of the novel, which has Gulliver turn more and more bitter throughout his journeys until he completely rejects humanity.

Even though there are only two stop-motion sequences, the film is gorged with special effects that kept Harryhausen so busy and stressed during the shooting in Spain that he developed dysentery. To create the illusion of the huge differences in height that are the core of the film required extensive optical and miniature work, all of which stand up well today in the digital world. Harryhausen avoided the standard rear-screen projection technique and instead used Rank Laboratories’ traveling matte process, and the results look impressive. The miniature sets for Gulliver blend well with the footage of the Lilliputians and the Brobdingnagians. One of the most impressive uses of a traveling matte and a miniature set is when Gulliver “sits in” on an outdoor court of the King of Lilliput. The combination between the two sets of footage combined in the traveling matte is seamless here. Also excellent are the oversized sets of Brobdingnag, such as the enormous chessboard where Gulliver gets to play the ultimate version of human-sized chess against the King.

Even though there are only two stop-motion sequences, the film is gorged with special effects that kept Harryhausen so busy and stressed during the shooting in Spain that he developed dysentery. To create the illusion of the huge differences in height that are the core of the film required extensive optical and miniature work, all of which stand up well today in the digital world. Harryhausen avoided the standard rear-screen projection technique and instead used Rank Laboratories’ traveling matte process, and the results look impressive. The miniature sets for Gulliver blend well with the footage of the Lilliputians and the Brobdingnagians. One of the most impressive uses of a traveling matte and a miniature set is when Gulliver “sits in” on an outdoor court of the King of Lilliput. The combination between the two sets of footage combined in the traveling matte is seamless here. Also excellent are the oversized sets of Brobdingnag, such as the enormous chessboard where Gulliver gets to play the ultimate version of human-sized chess against the King.

Kerwin Mathews is quite good as Gulliver; he’s actually far better as Gulliver than he is as a “white picket fence” Sinbad in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. He looks the part, and although a U.S. actor he shows a good sense for the eighteenth-century English milieu. Most of the character actors playing Lilliputians perform their parts with the appropriate energy and feel for Swift’s material, even if that material doesn’t always show up in their lines. It’s a pleasure seeing Peter Bull essentially playing the same character he would portray in Dr. Strangelove a few years later, only minus the Russian accent.

Child actress Sherri Alberoni gets an impressive credit “as Glumdaclitch” in the main titles, and she’s a naturalistic and charming addition to the movie as it starts to grind down during the second half. Alberoni went onto voice-actress fame in Josie and Pussycats (she voices Alexandra Cabot) and The Superfriends. However, she gets briefly upstaged by what I think is the single best human performance in the movie, the uncredited Waveney Lee as Shrike, the daughter of the quack royal doctor of Brobdingnag. Crikey, but this little girl is aggressively spooky. I’m afraid she’d slit my throat in my sleep if she were my daughter.

Enough about the people. The two animated creatures deserve special mention, since they are what will draw most viewers to the movie. The Brobdingnagian squirrel isn’t much to talk about: it pulls Gulliver down into a hole and then snarls a few times at Elizabeth (in a sound Harryhausen bemoans as “more like a wheeze than a squeak”) before disappearing. The model and the animation look good, but the creature makes little impact because of its brief screen-time.

However, the encounter between Gulliver and the titan alligator, which the king of Brobdingnag forces him to duel, is a great piece of work and the film’s highlight — it almost saves the whole second half. Harryhausen mixes the close fighting between Gulliver and the ‘gator (using scrolling effects to give the illusion of camera movement) with overhead shots of the court of giants watching the action. The trickery used here makes the interaction between Mathews and the animated creature near perfect. As he did in the duel with skeleton in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Mathews shows how skilled he was at acting out scenes with absolutely nothing and making it look believable. The sequence has the feeling of a classic knight vs. dragon battle, and it carries the electrifying fantasy feel that the picture needs in so many other places. Harryhausen is proud of what he did here, and rightfully so.

However, the encounter between Gulliver and the titan alligator, which the king of Brobdingnag forces him to duel, is a great piece of work and the film’s highlight — it almost saves the whole second half. Harryhausen mixes the close fighting between Gulliver and the ‘gator (using scrolling effects to give the illusion of camera movement) with overhead shots of the court of giants watching the action. The trickery used here makes the interaction between Mathews and the animated creature near perfect. As he did in the duel with skeleton in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Mathews shows how skilled he was at acting out scenes with absolutely nothing and making it look believable. The sequence has the feeling of a classic knight vs. dragon battle, and it carries the electrifying fantasy feel that the picture needs in so many other places. Harryhausen is proud of what he did here, and rightfully so.

Bernard Herrmann provided one of his best scores for The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, and he must have enjoyed that experience tremendously because he hopped right aboard for this voyage (as well as the Mysterious one and the one with Jason and the Argonauts that followed). Herrmann’s score for The 3 Worlds of Gulliver is another brilliant and colorful work, packed with a variety of orchestrations and a loving embrace of eighteenth-century English music. The main march captures the “Three Worlds” with a grand British Empire flourish, a miniature step for the Lilliput, and heavy brass and bassoons for Brobdingnag. Herrmann also composes a pleasant pastoral love theme for Gulliver and Elizabeth. His best piece in the film is the tremendous pursuit music for the finale, where he creates an intense feel of Brobdingnagian size as the giants chase Gulliver and Elizabeth. The score heard on its own (there are some superb re-recordings of it on CD) has a better sense of fantasy and Swiftian satire than the actual film.

In closing, I would like to make mention of producer Charles H. Schneer, who formed a long-lasting partnership with Ray Harryhausen from the mid-‘50s until Harryhausen’s retirement after Clash of the Titans in 1981. Schneer died in January of this year, mostly unnoticed among fandom, but we owe this man an enormous amount. Harryhausen’s effects get the most attention from viewers and critics, but without Schneer none of these films would have even gotten made in the first place; he had the intelligent producer’s eye to see what the special effects master could do, he had a similar love of colorful fantasy material, and he had the production skill to turn the small budgets into epics. Schneer was a special kind of creative producer, and without him our world would have been a much duller place.

[…] on this blog, I wrote about one of more ignored of Ray Harryhausen’s films, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. This inspired me to review two other films of his that don’t get enough attention—the […]

[…] Schneer’s color films. It followed the global success of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and the tepid The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. Like Gulliver, it goes to the well of classic public domain literature, but Verne is better suited […]

[…] often forget that he was an all-arounder when it came to visuals. The First Men in the Moon and The 3 Worlds of Gulliver depend more on model work and optical trickery than stop-motion, and all of it is wonderful. But […]