Short Fiction Review #16: We’ll Always Have Paris by Ray Bradbury

In his for the most part disdainful observations of science fiction as a cultural phenomenon, The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of, Thomas Disch characterizes Ray Bradbury, among other notable genre authors of the post- WW II generation, as being in “affluent decline” by the 1980s, suffering from “the literary equivalent of repetition compulsion” (122). He also rues that SF is a young man’s game, not because it is physically exhausting, but because the marketplace focuses on a largely juvenile audience in terms of intellectual temperament, if not actual age. Established authors such as Bradbury who remain successful within the genre do so because they have a “permanent mind-set that is ‘forever-young'” (213). I don’t think this is meant as a compliment.

I can only wonder what Disch may have thought of Bradbury’s 2007 Pulitzer Prize special citation. But, I have to admit he has a point.

Quick, name any Bradbury fiction written after the 1960s that had remotely any affect on you similar to The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Dandelion Wine (1957), A Medicine for Melancholy (1959) or Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962)? And if you weren’t a baby boomer reading any of these works at the so-called golden age of wonder, i.e. 12, and most likely male and most likely a bit of a nerd, during an era roughly contemporaneous to their publication, give or take a decade, you probably have no idea what the point of the question is.

As an aforementioned male baby boomer nerd whose reading of The Martian Chronicles in the fifth grade weaned me off of Hardy Boys books (for further details about this awakening, see this), Ray Bradbury is why you’re reading this (go ahead, blame him). Bradbury was my literary hero, though, for me, these days he’s something of a faded hero. The problem is that I’ve grown up, while Bradbury seems stuck in perpetual small town adolescence, a side trip to Europe or Mars or Los Angeles notwithstanding. For some readers, sometimes you can’t go home again.

It is also true that much (though, not all) of science fiction and fantasy has grown up, too. These days, it is sometimes hard to distinguish, except in marketing terms, what’s mainstream literature and what’s genre. Bradbury himself for a long time has published in mainstream publications stories set in non-fantastical situations, albeit in the same prose style of fantastical wonderment that characterizes his writings, whether they concern rocket men or hard working Illinois salesmen.

Which brings me to We’ll Always Have Paris, Bradbury’s most recent short story collection which appears, like much of his recent work — Farewell Summer and From the Dust Returned — to comprise reworkings of previously discarded and/or unsold material. The guy is, after all, 89, so he should be allowed to coast.

To what degree any of these previously uncollected and presumably unpublished stories have been edited or revised for this edition is uncertain, and perhaps irrelevant. While Bradubury in his introduction says that the stories came to him at various points in his life — “..from a very young age through my middle and later years” (xii) — there’s little indication from tale to tale that they were written by anything other than a man who has maintained throughout his long life the worldview of a young man’s wonder of the sheer fact of being alive.

Not necessarily, contrary to Disch, a bad thing.

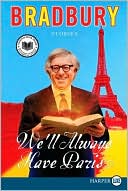

First impressions are not promising. You might not want to judge this particular book by its amateurishly garrish cover featuring a middle-aged Bradbury with a godawful reddish image of the Eiffel Tower superimposed on his suit jacket that most any seven year old could have done a better job of photoshopping. But it’s not as bad as you might fear, though it has more than a few that make you wince in the realization that without the Bradbury nameplate a few of these would never have transitioned from the rejected pile to the printed page.

The title story, an obvious allusion to Casablanca that has little to do with it beyond that of a relationship that can’t be fulfilled, depicts, of all things, the narrator’s (Ray’s?) brief homoerotic, though not even close to consummated, encounter with a young male Parisian. Since this is Bradbury, it is, of course, perfectly charming, if somewhat pointless.

Homosexuality also figures in “Come Away with Me” (does Ray listen to Norah Jones?), though the abusive relationship depicted could just as easily have been heterosexual. Joseph Kirk is intolerant of those who degrade others. Even though it is none of his business, Kirk rescues a young man from the verbal assaults of his lover. Kirk knows neither man personally, and, as a straight married man, has no interest, sexual or otherwise, in the young man he defends. Kirk takes the young man, Willy-Bob (I kid you not), under his wing, tries to give him some manly advice about not taking any crap from anyone, but to no avail as Willy-Bob returns to his submissive role with his boyfriend. Not hard to figure out why this one was never previously published.

Like everything else in Bradburia, homosexuality is depicted through the idealized prism of a Depression-era midwestern mentality in which the strongest oaths consist of “goddamn” and “bastard,” beautiful wives tolerate the antics of their menfolk who have simple commonplace names like “Smith” and “Hill” and “Joe,” music is played on phonographs, movies appear in black and white and the circus is coming to town, while all the while odd shadows lurk beneath the wondrous experience of breathing air and loving words. Sometimes loving words a little too recklessly. While Bradbury’s over-the-top exuberance to coin a phrase is for the most part held in check, occasionally you will run across things like this from “Massinello Pietro”: “His house, his Manger, his shop, different! Filled with squeaks and stirs and mutters of bird sound, filled with feather whisper and murmurings of pad and fur and the sound that animal eyelids make blinking in the dark” (7). Let’s stop and think about that for a second. Exactly what kind of sound do blinking eyelids make? And who can hear it? But the more you do think about it, and realize it is describing something unreal, it does leave you with an image that is strangely evocative. At some level, eyelids must make some kind of noise going up and down. Are zoos filled with a cacaphony of blinks that maybe only the “lower” animals can detect? But for Bradbury, it probably doesn’t much matter, any more than how rocket ships could actually work, it’s just all part of an imaginary world that’s more goshdarn extraordinary than mundane reality.

There are four stories here of particular note, a reminder that even Bradbury at his most eccentric can still be thought provoking. In “Ma Perkins Comes to Stay,” Joe Tiller comes home to find a radio character entrenched in his living room, and a wife who likes her company despite her husband’s protests. At first, I thought this was going to be another Twilight Zone type ending that characterize too many of the tales here. And while it is, the depiction of a reality invaded by radio characters is more in line with Fahrenheit 451 in “predicting” the dangers of seemingly harmless entertainment. It’s kind of cool that he can do this in employing a 1940s radio personality from the supposed good old days, although younger, twittering readers may well wonder who the hell Ma Perkins was.

“Apple-core Baltimore” is a redemption of the nerd tale, in which the aforementioned visits the grave of his supposed friend and finally, after all these years, gets some psychological revenge to top off the best revenge of all, namely staying alive. Also largely non-fantastical is “Pietá Summer,” which depicts a father’s love for his son and vice-versa.

The main attraction is “Fly Away Home,” a sort of outtake from The Martian Chronicles. A military contingent (comprised, of course, only of men, remember this is the future as it takes place in the Eisenhower era) are on expedition to colonize the barren red planet, somehow able to breathe the air and seemingly not there for any other reason than to be there. Problem is, they get homesick. The solution? Set up a makeshift main street, complete with the pretty girl behind the drug store soda fountain along with a hint that other young ladies of another sort might be found in rooms above the tavern, where they serve rye, straight up.

That’s the Bradbury that enchanted me when I was in fifth grade. And, now in my fifth decades, still does.

Having recently introduced my son to Bradbury’s short stories, I found this entry especially relevant. When I was in grade school you could count on at least one Bradbury story being in the class reader; times have changed, and my son hadn’t seen The Sound of Thunder, or The Foghorn or The Blue Bottle, or many others I still remember fondly.

I too was thinking about Bradbury, and was trying to find a version of The Martian Chronicles that collected ALL of his stories set on Mars. I’d heard that such a book existed. Turns out it doesn’t exist yet. It is due to be printed, but the price tag will leave it out of the range of most mortals. I hope that some enterprising publisher will pick up the trade paperback rights so that anyone interested in having the fiction readily at hand without buying every Bradbury short story collection can afford it. Anyway, here’s a link:

http://www.subterraneanpress.com/Merchant2/merchant.mv?Screen=PROD&Product_Code=bradbury09&Category_Code=B&Product_Count=16

[…] — as well they should, this is, after all, Bradbury in his prime — than his latest We’ll Always Have Paris that I recently reviewed. Even from my adult […]