Read Planet: Kline’s The Swordsman of Mars

I read The Swordsman of Mars out of a sense of obligation, which is probably the worst way to read anything, and with the firm conviction that it would suck. That’s the word on the virtual street about Otis Adelbert Kline: he’s a poor man’s Edgar Rice Burroughs. So I was thinking: ERB, without that mellifluous prose style and brilliant plotting. Urk.

Well, I was completely wrong. I enjoyed the book enormously, but that’s not all. You can enjoy almost any piece of writing if you approach it with the lowest possible expectations (and, yes, I am thinking of Lin Carter‘s multifarious pastiches here). I came away from it with considerable respect for Otis Adelbert Kline as a writer of fantastic fiction.

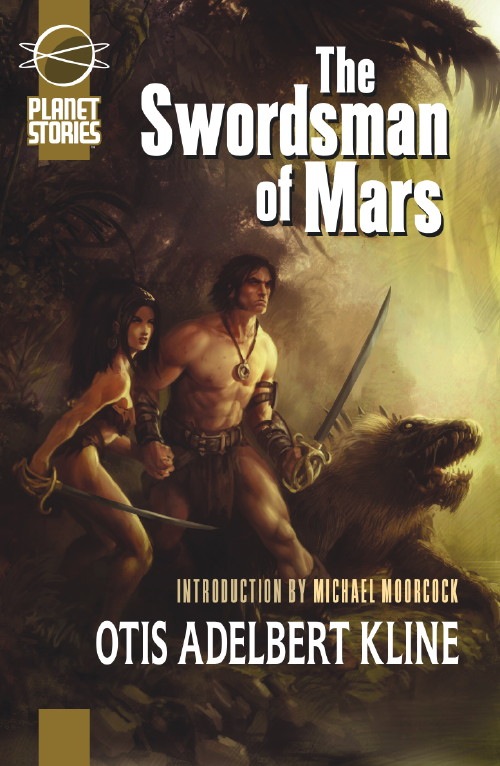

Some details: I read the book in the recent Planet Stories edition and I recommend that others do the same. (I know this sounds like I’m on the pad for them, but I assure you the payoff did not go as planned there is no truth to that rumor.) Originally serialized in Argosy, the novel appeared in book form first in the 1960s, those “go-go” years that saw the great boom in paperback adventure fantasy. It was pretty heavily abridged for Ace’s Draconian space requirements, possibly by the savage hand of Wollheim. (Actually, no one knows who did the abridging, but I badly wanted to use the phrase “savage hand of Wollheim.” It would make a great title for something, maybe a Viking novel.) The Planet Stories edition has a thoughtful and informative introduction by Michael Moorcock, who knows something about these matters, and a clean text of the original serialized version of the novel, with an evocative cover painting by Daryl Mandryk. (For those who, like me, can’t get enough of this stuff: the sequel, The Outlaws of Mars, is due out from Paizo early next year.)

The Swordsman of Mars is decidedly within the narrow limits of sword-and-planet as established by ERB. As someone recently put it: “a lone American (not a Canadian–not a Ugandan–not a Lithuanian–an American) is mysteriously plunged into an exotic other world which is both more advanced and more primitive than the earth he knows. He conquers all by virtue of his heroism and marries the space princess.”

Lone American: check. His name is Harry Thorne; he’s a down-on-his-luck scion of a rich family whose shallow sweetheart has just dumped him.

Mysterious plunge to another world: check. As a substitute for the suicide he was about to attempt, he agrees to trade bodies (via astral projection which–stop snickering or I’ll turn this syllogismobile right around!) with a Martian adventurer named Takkor who happens to be his doppelganger.

Space princesses: double check. There are two on hand for our hero to flirt with. I won’t tell you which one he ends up with, but you knew it would be one or the other and it is.

The heroism I will leave you to discover for yourself, but it does have some interesting aspects. At one point Thorne is sentenced to slave until his death in the deadly baridium mines. He is befriended there by a guy who helps him survive. When the inevitable rescue comes, Thorne insists that his friend be taken out with him and won’t go unless his friend is allowed to go too. Against opposition, he wins his friend’s freedom. Then there’s a fight with some thugs and his friend is killed anyway. It is a strikingly somber note in this colorful adventure tale. Later, Thorne and his “faithful retainer” Yirl Du are fleeing from the villainous Ma Gongi. Yirl Du is captured and there is nothing Thorne can do about it. So… he does nothing. The faithful retainer later escapes, but that’s not due to anything the hero does. This struck me as somewhat frosty, but maybe realistic. It made me think less of Thorne, but it was an interesting choice by Kline.

Kline’s characters are not finely detailed, but his women are worthy of mention, especially Thaíne: a beautiful, fierce and intelligent warrior-maiden who lives in the marshlands with her faithful dalf Tezzu. (A dalf seems to be a cross between an alligator and a wolf.) Many sword-and-planet adventures are spackled with passive, object-like women, but OAK doesn’t go in for that. The other space princess in the book is more conventionally princessy, but she takes significant action through the story: she’s not just waiting around for some jeddak to rescue her.

Kline’s villains vary in quality. The Ma Gongi are interesting–evil moon men intent on refighting the interplanetary war that devastated their planet–but none of them rises to the level of an individual. The native Martian villains are hypocritical advocates of a fraternal philosophy which sounds a great deal like (and is evidently meant to sound like) Communism. This is potentially interesting, but OAK’s handling is a little too clumsy to make his message effective. Here’s Thaíne’s summary of the situation:

Once [my father] was Vil of Xancibar with a magnificent palace in Dukor and two hundred million subjects to do his bidding. There was a revolt led by a man named Irintz Tel, who wished to establish a new order of government, abolish all property rights and make all men servants of the state.

That was very wrong of him, no doubt, but it doesn’t really establish a clear superiority for either side–more like a matter of “meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” The Vil is an absolute monarch whose office is apparently both hereditary and elective. So you know it’s got to… I mean, it… No, I don’t think it makes any sense. (It’s a floor wax and a dessert topping!)

The principal antagonist is another American, a rather low-class fellow you will be shocked, I’m sure, to hear, who preceded Thorne to Mars via astral projection and goes by the moniker Sel Han (alias Frank Boyd). He throws in with V. I. Lenin Irintz Tel and seems inclined to make the best of things on the Red Planet. (See what I did there?) In one of the funnier scenes in the book, he confronts Thorne and talks to him in English, of a sort.

“Don’t get stormy with me, wise guy,” said Sel Han. “I came here to make you a proposition. If you don’t like it, all right. I can put you on the spot. If you are a right guy and want to ride along I can make a big shot out of you. What do you say, Harry Thorne?”

Thorne says what you might expect and the fight rages on, but this was the scene where I became conscious of how well OAK writes. The “hey, mac” quality of “Han”/Boyd’s English stands out (deliberately on OAK’s part, I’m sure) because no one else talks like that. The other characters, without affecting ye Olde Corninesse, all speak in a less colloquial style, and they don’t all sound the same. Kline is a deft (and usually unobtrusive) stylist.

The Mars of the book is a rather damp and densely populated world. I found this difficult to wrap my head around, since the pulpy tradition of Mars as a wasteland is so strong in my imagination (reinforced by the bitterly cold and dry reality that we’ve since had drummed into us). But it’s OAK’s universe and he gets to call the shots, and he builds his world out of interesting elements: varied topography, giant predatory giant mosquitoes, dalfs, elflike Winged People, etc. OAK has a knack for cool inventions, too: in the escape from the mines Thorne and his faithful retainer Yirl Du use “desert legs”–stilts with springs that make it possible to cross the desert swiftly and safely. One doubts they’d really work, but the descriptions of striding like giants across the desert landscape and leaping from great heights were fun to read. The colored death rays that the Martians and the moonmen use to wage war are more conventional, but you couldn’t leave Earth without packing polychromatic death-energy in those days.

Conventional, but not wholly so, is not a bad summary of the book. OAK enriches the genre without transforming it. If you don’t like the sword-and-planet genre, The Swordsman of Mars is not the book that will make you a convert. If you don’t know whether you like it or not, this might be a book worth trying. If you’re already a fan of sword-and-planet you’ll want to read this, even if (perhaps especially if) you’ve already read one of the earlier, silently abridged editions.

I was pleasantly surprised by this too, definitely better than I thought it would be.

Yes, I think OAK definitely gets the benefit of lowered expectations. I wonder if Outlaws of Mars will suffer from expectations that are too high?

IMHO, The Outlaws of Mars is in fact better than Swordsman. The story is tight and it’s a great romp for fans of pulp adventure. Hope you’ll check it out.

[…] was reading buckets of sword-and-planet last year (some of which I reviewed in this space) and it constantly occurred to me that the aboutness of these books is concerned with male […]