‘On Thud and Blunder’ — Thirty Years Later

. . . writers who’ve had no personal experience with horses tend to think of them as a kind of sports car.

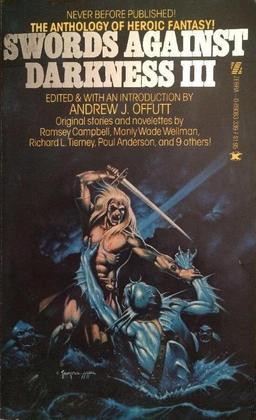

It’s been thirty years since Poul Anderson wrote his essay on the need for realism in heroic fantasy, ‘On Thud and Blunder,’ which you can read in its entirety at the SFWA site, and I think it holds up well even though the genre — and the perception of it — has changed greatly. ‘On Thud and Blunder’ originally appeared in the third installment of Andrew Offutt’s classic anthology series Swords Against Darkness; though it was in the excellent, if unimaginatively named, collection of Anderson’s called Fantasy that I first encountered it. But already at the time of my reading a whole generation of writers had made a name for themselves by following the dictates of realism and common sense in designing their fantasy worlds.

The essay begins with a satire of the genre that features a barbarian cleaving through armor with a fifty-pound sword and riding a horse as if it were a motorbike, among other ridiculous things. It’s the kind of thing that gave heroic fantasy and sword and sorcery a bad name, and perhaps the sort of thing that meant it would soon be eclipsed by a rising tide of ‘high fantasy’ in the eighties and nineties. But, in 1978, hf — as Anderson terms heroic fantasy in an abbreviation that seems to have never caught on — was an emerging star:

Today’s rising popularity of heroic fantasy, or sword-and-sorcery as it is also called, is certainly a Good Thing for those of us who enjoy it. Probably this is part of a larger movement back toward old-fashioned storytelling, with colorful backgrounds, events, and characters, tales wherein people do take arms against a sea of troubles and usually win. Such literature is not inherently superior to the introspective or symbolic kinds, but neither is it inherently inferior; Homer and James Joyce were both great artists.

A wonderfully concise statement in defense of the genre, something I could easily see being forwarded today on some blog in support of the much-hoped-for internet revolution in pulpish storytelling. However, on today’s bookstore shelves, it isn’t sword and sorcery but high fantasy books that are all the rage — a genre possessing a set of conventions that do tend to nicely address the concerns Anderson raises in ‘On Thud and Blunder,’ but one that itself brings a whole host of new excesses to the table. Perhaps a contemporary writer of Anderson’s perspicacity could produce a follow-up article aimed at high fantasy’s faults, which I propose be titled ‘On Bloat and Blather.’

But that is not to say I dislike high fantasy, far from it. I no more dislike it than Anderson does hf when he lampoons it. Nor is that the focus of this post, I merely wanted to suggest how the background of fantasy publishing has shifted dramatically — so dramatically, in fact, that many of the virtues Anderson enumerates have themselves been used to excess by certain authors in the quest for better fantasy worlds.

Another thing that Anderson decries that has changed for the better, though perhaps not to the extent that it should, is the development of fantasy worlds based on histories and mythologies outside of the European and Near Eastern tradition. Already in the seventies the shift could be seen, and on today’s shelves, too, an increased variety of influences are in evidence. While many veins of culture remained to be tapped, there are at least Asian, African, and Native American inspired fantasies available — even if the generic brand of fantasy remains overwhelmingly a bland distillation of Medieval Europe.

Another thing that Anderson decries that has changed for the better, though perhaps not to the extent that it should, is the development of fantasy worlds based on histories and mythologies outside of the European and Near Eastern tradition. Already in the seventies the shift could be seen, and on today’s shelves, too, an increased variety of influences are in evidence. While many veins of culture remained to be tapped, there are at least Asian, African, and Native American inspired fantasies available — even if the generic brand of fantasy remains overwhelmingly a bland distillation of Medieval Europe.

Though all of that is incidental to the purpose of Anderson’s essay, which is a call for greater realism in fantasy — and not merely realism, but logic and common sense, too. Anderson does a wonderful job of skewering so many of the misconceptions and lazy assumptions of the genre, bringing his historical knowledge to bear on such things as the day-to-day realities of a pre-industrial society, the likely workings of politics and religion, and, of course, some of the practical aspects of fighting and combat. ‘On Thud and Blunder’ does more to get the reader thinking in these terms, and inspired to go out and do some research, than a great many of today’s shallow, cynical books written on the subject of world building and aimed at the would-be fantasy writer.

And, while this essay is targeted at writers, ‘On Thud and Blunder’ will be appreciated by anyone interested in both fantasy and history. Anderson throws off interesting historical anecdotes like sparks off a grinding wheel, from the pervasiveness of disease and the development of cities, to the social underpinnings of a nation’s army and the fragility of a horse’s health. It is fascinating stuff — and for a writer looking for ideas, it’s a goldmine.

It has sometimes been said that we are now witnessing the Golden Age of fantasy — and, with so many series out there varying from the extremely sophisticated to the utterly banal, it’s hard to disagree with the statement at least from the standpoint of quantity. It seems to me fantasy has had to change from its sword and sorcery roots in order to generate the mass appeal that it now holds; it had to get away from many of the flaws Anderson is drawing attention to. In some ways it’s a shame that the pendulum has swung so far away from the rollicking good action tale, but it does show signs of swinging back and, perhaps, ushering in a new crop of tales at once sophisticated and viscerally paced. I don’t know if this really is the Golden Age, and I can’t claim that I like all the changes I see in the genre, but I do believe fantasy has improved with time — and I fully expect it to get even better.

BILL WARD is a genre writer, editor, and blogger wanted across the Outer Colonies for crimes against the written word. His fiction has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, as well as gaming supplements and websites. He is a Contributing Editor and reviewer for Black Gate Magazine, and 423rd in line for the throne of Lost Lemuria. Read more at BILL’s blog, DEEP DOWN GENRE HOUND.

[…] Click here to read ‘On Thud and Blunder’ — Thirty Years Later […]

Thanks for this: I’m a big Anderson fan and it’s a pleasure to reread this article. I first read it in that same volume, too, the Tor collection Fantasy–a rotten title for a great book.

The issues have certainly changed in 30 years. It seems to me there’s no lack of period detail in imaginary world fantasies–maybe too much detail, sometimes, obscuring the line of the story. But it’s still the authentic points of concrete imagination that strike deep, and Anderson was a past master at those.

Thank you for posting this.

It’s something I was trying to put my finger on a while back.

I even started a post about one of these topics over on the official REH site about fighting styles. You see these old black and white pictures of REH where he’s either boxing, or has swords, or guns. And my post was simply asking, what type of fighting skills did REH possess. It is obvious to me when you read any of the fight scenes that he really understood personal combat, the ebbs and flows of a fight, etc. And there are intricacies to blade fighting that you might not pick up on, unless you have at least a rudimentary understanding of it. Ah well, i find it to be quite fascinating.

[…] read with interest Bill Ward’s entry two weeks ago about Poul Anderson’s famous essay, On Thud and Blunder. While I agree with Ward that […]

[…] Black Gate — “It has sometimes been said that we are now witnessing the Golden Age of fantasy — and, with so many series out there varying from the extremely sophisticated to the utterly banal, it’s hard to disagree with the statement at least from the standpoint of quantity. It seems to me fantasy has had to change from it’s sword and sorcery roots in order to generate the mass appeal that it now holds; it had to get away from many of the flaws Anderson is drawing attention to. In some ways it’s a shame that the pendulum has swung so far away from the rollicking good action tale, but it does show signs of swinging back and, perhaps, ushering in a new crop of tales at once sophisticated and viscerally paced. I don’t know if this really is the Golden Age, and I can’t claim that I like all the changes I see in the genre, but I do believe fantasy has improved with time — and I fully expect it to get even better.” […]

[…] a retrospective essay, Bill Ward notes that Anderson unleashed his frustration at heroic fantasy just when Tolkienesque […]