Apprehend a little calorie is secured

When Howard first asked me–among several other Black Gate writers–if I would like to blog regularly for the web site, my first concern was about internet access. This was back in July, and I was soon to head off-grid for a yearly visit with my family in British Columbia, and after that to Dubai, where my spouse had taken a job, and where the government grants internet service only to those with residency visas, which he did not have yet. We didn’t get connected until the beginning of November. Fortunately, the web site wasn’t ready for us until the last few days! Now my concern, as a s..l..o..w writer, is generating content on a weekly basis…

At the start of a blogging endeavor it seems appropriate to introduce myself. I’m a writer of sf and fantasy whose academic background is in anthropology, oral literature, ethnolinguistics, and ethnohistory, and my geographic area of specialization is the indigenous north Pacific coast of North America. I post periodically about Dubai in my personal blog, and my website has a list of my fiction publications. Within the larger sf/f genre, I write all over the map, and at conventions I find myself on panels on shamanism and myth as often as those on the economics of space travel.

At such occasions and elsewhere I have witnessed much sub-genre bashing on all sides. I have also, when talking with people outside the genre, encountered more than my share of dismissive opinionating on the topic of sf and f in general (no doubt an experience shared by many readers of Black Gate) and, from within the genre, corresponding dismissiveness towards so-called mainstream fiction.

With regard to fantasy–the topic here–much of the bashing seems to come down to the view that the sub-genre is pathologically nostalgic, that it consists of little more than the endless recycling of the same tired cliches, and that writing fantasy is “easy,” in part because of its cliche-ridden nature and in part because in fantasy worlds, writers “can just make everything up.” There is, absolutely, too much fantasy that fits this stereotype. The topic of conventionalization in fantasy, however, is a much broader one that goes to the heart of how I think about genre, literature, and storytelling of all kinds, and I’d like to say just a few things about it in this first post.

One aspect of living in Dubai that I have not written about at my LiveJournal is the nature of communication here. Eighty percent or more of Dubai residents are expatriates from all over the world. English is the common language, but it is the first language of very few. Many people appear at first contact to speak English, but turn out only to be able to say or respond to a limited number of stock phrases, and much of the time will not tell you when they don’t understand you. Any transaction that deviates from the scripts they have memorized soon degenerates into chaos. I only wish I could provide a transcript of a call we made to Ikea Customer Service querying whether we had purchased the right kind of furniture treatment for our new put-it-together-yourself table. (I eventually realized that the transaction must have foundered over the term “unfinished furniture.”)

Having come up as a scholar through the study of unwritten languages and folk literature, I have a great respect for convention. All language, for example, depends upon shared conventions that govern how we parcel sounds and strings of sounds into meaningful categories. These rules do not determine what we say, but are rather the necessary tools for saying it.

Successful storytelling similarly depends upon many kinds of conventions, and from a folklorist’s perspective, all stories are examples of one genre or another. What distinguishes any given genre is its particular constellation of stock elements along with its rules for combining them. Moreover (I would add), every genre has its own bell curve of conventionalization, from the completely cliched and predictable to stories that are barely comprehensible within the genre’s framework.

Communications consisting purely of stock elements–between store clerk and customer, between writer and reader–can work, but only if the subject matter and the needs of the participants never vary. Outside of this very narrow frame, however, attempts at communication are at constant risk of disintegrating into meaninglessness.

Customer: Do we have the right finish?

Ikea Customer Service: You need to finish your furnitures, sir?

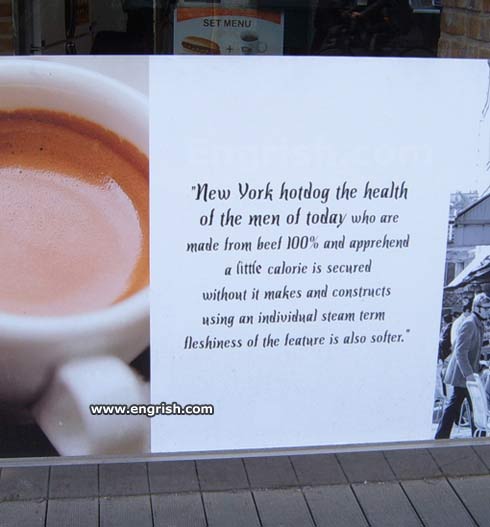

At the other end of the bell curve are communications that where the use of the relevant conventions is radically insufficient. These also can quickly descend into chaos. Take, for example, this sign (from Korea rather than Dubai) posted recently at that wonderful archive of under-conventionalized language, engrish.com:

Conventions, in other words, are not in and of themselves the enemy of literary value (howsoever that may be assigned) any more than the rules of English syntax and semantics are the enemy of comprehensible speech. Conventions are what make it possible for a writer to arouse the reader’s interest and to satisfy the reader’s expectations–to create meaning. As a reader, the most satisfying stories for me are often those that manage to find a middle ground and place conventions at the service of the unexpected. As a writer, my own creative process is often a dialectic between the raw power of convention to shape a story on the one hand, and my reaction to those conventions on the other, which often means wanting to tear them apart and reassemble them. A broad topic, as I said, and one I hope to come back to.

I like the idea of conventions creating meaning (or sometimes blocking its creation), especially because they tend to be socially determined. And genre turf wars typically boil down to: “We are This Kind of Person–we are not That Kind of Person Reading/Writing That Kind of Icky Stuff.” A social grouping justifies the genre, which justifies the social grouping. But if there is some permeability along the genre’s borders, there will probably be some along the group’s borders also.

The way in which social meanings get mapped onto linguistic or literary conventions is another big aspect of it! I’m reminded of stuff my sociolinguistics professor, Bill Labov, used to say about the connections people make between certain phonemes and social status (for instance so-called R-less dialects in New York City). The absolute arbitrariness of that is maybe most visible when you’re learning a foreign language. With stories and genres, though, I think there are other factors at work, for instance the degree to which a genre’s conventions lean toward particular emotional interests, or whatever the best term might be, and whether those are stigmatized or valorized in the larger culture.

Labov was my hero as a linguistics undergrad (before I switched back to Latin). It was fascinating how he got at the gulf between actual speech performance and self-reporting.

I’ve been thinking lately that genres fall into two types: ones that elicit a particular emotional response (horror, comedy, romance) and ones that have a certain set of furniture (i.e.: swords + spells > s&s; sixguns + rustlers > westerns; Professor Babbage’s Steam-Powered Thinking Machines + zeppelins > steampunk). Whether this is socially-driven or not is hard to say, but certainly fans of the second type (in which I include myself) may be more prone to the “my genre, my self” thinking.

I know that the emotional response thing is a classic way of looking at (sub)genres, and that fantasy doesn’t usually fall into the category of those that are defined in terms of emotion. This summer I was on a panel with David Swanger, who’s written on the emotional roots of fantasy. I can’t locate an online version of the article (it was published in NYRSF which is only slowly coming into the internet age), but I think I have one hiding somewhere on my hard drive–will have to look it up.

What I originally meant by “emotional interests” was something rather different than what David is talking though. An example would be the emotional appeal of stories in which ordinary (or, better, marginalized) boy/young man discovers hidden GREAT POWERS and saves the ENTIRE universe. This is not where my personal emotional interest lies, though I’m happy to read such stories if there is enough other stuff going on in them. Or, vampire romances featuring very manly alpha males drinking blood and falling for the mundane but extraordinarily beautiful heroine. There’s no compelling interest there for me. Obviously, however, both subgenres do hold intense emotional interest for many.

[…] my previous post here I wrote about conventions in communication, and this is really the same issue, or at least it’s connected in my mind. A more general […]

This is an absolutely fascinating post. It makes me think about what I loved about Gene Wolfe’s Wizard Knight duet, in which he seems to use familiar tropes to set up, and then mess with, reader expectations. In those books, not only is the language and narrative beautiful, but the conventionalizing itself is turned into a wonderful work of art in its own right.