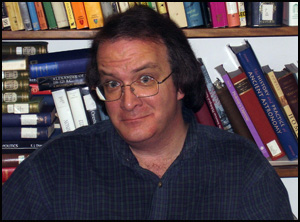

James Van Pelt has posted some great articles on writing the last two days — one on April 23, one on April 24. You owe it to yourselves to check them out here:

A few years back, when I was reviewing for Tangent and reading widely to get a better feel for various markets, I ended up reading a lot of stuff that wasn’t my cup of tea. James can be found in all sorts of magazines, and I quickly discovered that he always delivered a nice story, even it it wasn’t the kind of tale I usually enjoyed. More to the point here — he really seems to know what he’s talking about, technique-wise, so I hope you’ll see what he has to say.

In the spirit of writing techniques, here’s some thoughts I jotted down for Daniel Blackston a few years back on description and ended up putting on the swordandsorcery.org site. I thought it might have some relevance to story beginnings as someone asked about last week.  A lot of tales I reject start with laborious descriptions of the main characters.

Writing Descriptively

I look on description as my camera. If I am analogous to the director of the film my readers watch, then description controls many of the aspects of that story experienced by the reader. That camera is critical for conveying pacing, setting, character, and plot.

Description does not sit statically — it has a purpose. Like makeup, it is applied sparingly to highlight or emphasize what we wish to show, to draw attention away from what we do not. It cues the reader as to what is critical to the story and ensures that a tale maintains momentum.

Either in the opening paragraph or within the first few lines of dialogue, our camera pans over the scene so that the reader sees the environment through which our characters move. Usually the characters are seen as well.

Lin Carter, editor extraoirdinaire and author of many thrilling tales of fantasy and science fiction, wrote Imaginary Worlds, on the history and techniques of writing fantasy, which should be a required read for all fantasy writers. Such writers also should run, not walk, to purchase Poke Runyon’s Drell Master, wherein is printed a letter from Carter about describing fantasy heroes and setting more useful than many semesters worth of writing classes. Here is a brief excerpt from that letter:

Notice how Burroughs describes a hero? Just a few brief sketches:

Tarzan is golden bronze like a Greek god. Fierce eyes under black mane. Moves with regal dignity and pantherine grace. That’s all. That’s enough. Or John Carter: lithe and sinewy, his naked body clasped in the Barsomian warrior’s harness, crusted with badges of rare metal and glittering gems, gem-studded butt of radium pistol, rapier hilt, dagger. Boots.

We do not need to know the color of every ring upon our hero’s finger, nor the subtle shape of his chin. Details in excess overwhelm.

Robert E. Howard was a master of description. Consider the following excerpt, the opening paragraph to “The Slithering Shadow” (also known as “Xuthal of the Dusk”):

The desert shimmered in the heat waves. Conan the Cimmerian stared out over the aching desolation and involuntarily drew the back of his powerful hand over his blackened lips. He stood like a bronze image in the sand, apparently impervious to the murderous sun, though his only garment was a silk loin-cloth, girdled by a wide gold-buckled belt from which hung a saber and a broad-bladed poniard. On his clean-cut limbs were evidences of scarcely healed wounds.

In this short paragraph we see setting, character, and even some hint of the challenges that lie both before and behind the protagonist. Howard fastens our eyes upon the interesting and we do the rest. Take careful note that the description of Conan doesn’t start at the top of his head and work down. Showing someone in that manner may be an efficient way to construct a prose painting, but it is rarely how we view people. We see them in motion, reacting to the environment through which they move.

Lest you think all successful description must read like Howard, consider Lord Dunsany, writing in a very different style as a neglected rocking horse remembers its master in “Blagdarossâ€Â:

…we would pass by night through tropic forests, and come upon dark rivers sweeping by, all gleaming with the eyes of crocodiles, where the hippopotamus floated down with the stream, and mysterious craft loomed suddenly out of the dark and furtively passed away.

These two enormously gifted writers, seemingly miles apart in subject matter and style, share much in common. They let verbs do the work. They carefully avoid was, were, and other forms of “to be.†Adjectives are used precisely to convey mood. And both writers anthropomorphise.

Let’s look at the first line of Conan’s paragraph. Howard might have written “the desert was shimmering in the heat waves†or “the desert sat shimmering in the heat waves†but he wrote “the desert shimmered in the heat waves. BAM. He wasted no time conveying his image. He avoided was, he used but one verb, and he avoided the “ing†form of the verb, a present participle in this sentence (although “ing” verbs are frequently gerunds).

Careful reading shows that skilled writers use action verbs. They do not zealously strip every gerund and every to be verb from their work (successful writing is never that simple) but rather employ those forms sparingly. We don’t see “Conan the Cimmerian was looking†we see “Conan the Cimmerian stared.†In Dunsany we don’t have the “hippopatumus was floating†we have “hippopatumus floated.†Without the to be verb and the gerund clogging our way the action is conveyed directly.

Particularly egregious would be “was floating†because it wastes time with a to be verb followed by a descriptive verb. You don’t need both. Use only the verb that paints a picture in the mind of the reader. Does your character head up the stairs, or does he race, stroll, pound, drag? To “head†up the stairs provides no picture. If you state merely that “he was a tall man†you waste the potential for emotional reaction, or even simply an interesting camera angle. “He towered over the other warriors,†say. Strive for both precision and economy, but do not employ these tools to such exclusion that your prose reads like parody.

Some excellent writers slather on adjectives to wonderful effect — but overuse of adjectives is more often a sign of bad writing. In the examples above Dunsany and Howard wield adjectives shrewdly to present pictures with just two words: “dark river†and “tropic forest,†or “blackened lips†and “murderous sun.†These words instantly present images.

There are schools of thought today that instruct writers never to use anthropomorphism. This is folly. We cannot help but ascribe motivations to the unliving objects around us; it is how humans instinctively think, and writers should use this inclination to their advantage. Shakespeare certainly did, and he should be studied devotedly by any who wish to succeed at writing. Consider Macbeth, who has tomorrow creeping at its petty pace and yesterdays lighting the way to dusty death. Howard’s murderous sun and aching desolation, and Dunsany’s mysterious craft passing furtively demonstrate how ably a little unscientific attribution dresses a scene.

Pacing and description are vitally linked. Too much description during an action scene and the moment conveys no excitement, too little and the moment is confusing. In dramatic sections the sentences or phrases should be crisp and short — flowery phrasing is fine for describing a melody or a sunset, but when the pace quickens, urge the reader along with fewer words. In a scene from Leigh Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon the protagonist, Carse, leads slaves to rebellion:

With belaying pins, with their shackles, and with their fists, the galley slaves charged in and the soldiers met them. Carse with his whip and his knife, Jaxart howling the word Khondor like a battle-cry, naked bodies against mail, desperation against discipline.

Note how the camera pulls back; in painting terms the scene is shown in broad strokes. In other instances the camera needs to focus tightly, providing the illusion that it shows every movement (it doesn’tâ€â€the eye should still be pointed only to the crucial aspects so that the reader does the rest). Still there is an economy of words to preserve momentum. Consider this excerpt from Harold Lamb’s “The Winged Rider:â€Â

They swerved into the fire and out again, their blackened boots smoking in the snow. Then Skal grunted. One of his ribs had broken. Ayub, grimly silent, tightened the grip of his steel-like arms.

Skal’s twisted face grew black and he screamed suddenly, choking as the breath was driven from his lungs. His arms went limp and he lay in Ayub’s grasp, his ribs cracked, his back broken.

While it should never be forgotten that all elements of a story are interlinked, when you contemplate description you should most remember precision, action, economy, and pacing.