Dark Muse News: Sword & Sorcery Chain Story (#14-#18)

In August 2025, we hailed the emergence of a second Chain Story project championed by Michael A. Stackpole. This is a Sword & Sorcery-focused, contagious set of connected (“chained”) stories. Each is:

- A standalone tale

- Readable in any order

- Free to read

- Interconnected via a theme involving a Crown

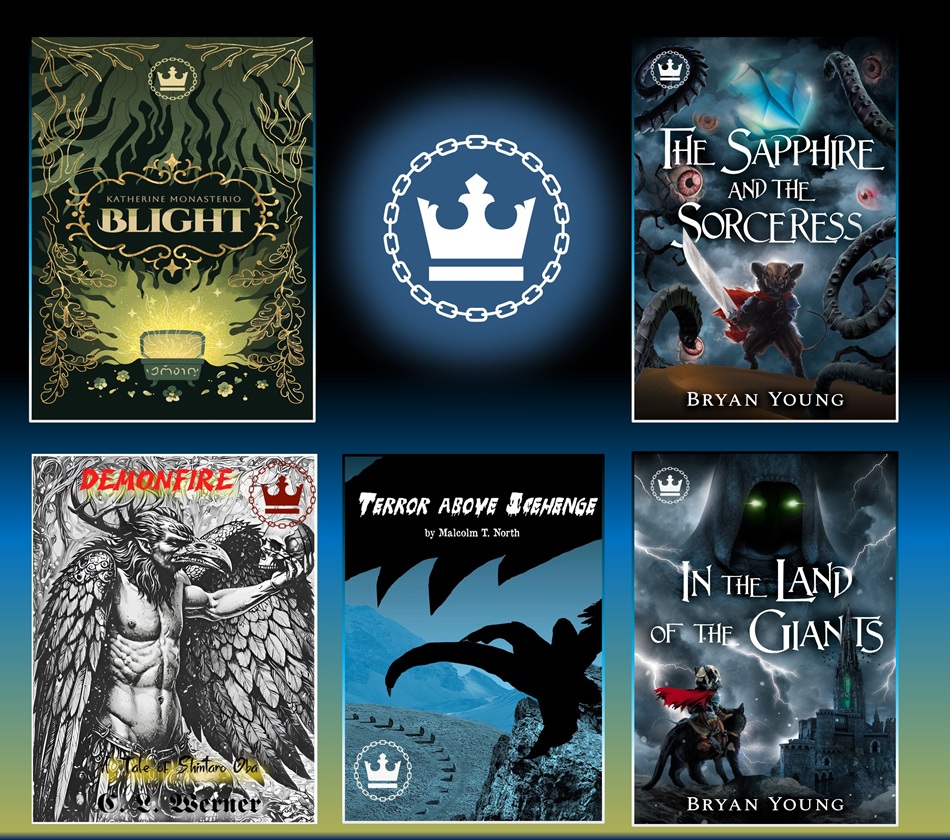

Stories are being released every few weeks. We’ll round up groups, but check the Chain Story website. for the latest. In this post we highlight the latest set of five, Episodes 14-18:

- 14 Blight by Katherine Monasterio

- 15 In The Land of the Giants, by Bryan Young (second in the series via the chain!))

- 16 Demonfire: A Tale of Shintaro Oba by C. L. Werner

- 17 Terror Above Icehenge by Malcolm T. North

- 18 The Sapphire and the Sorceress by Bryan Young (third in the series via the chain!)

Previous Black Gate posts have chronicled groups of the growing chain:

- The Chain Story 2 – Sword and Sorcery Entries 1-3 (Aug 2025)

- The Chain Story 2 – Sword and Sorcery – Episodes 4-8 (Oct 2025)

- The Chain Story 2 – Sword and Sorcery – Episodes 9-13 (Nov 2025)

The Chain Story 2 – So Far

Entry |

Chain Post Link/Date |

Story(Link to Free version) |

Author |

Abstract |

| 18 | January 19, 2026 | The Sapphire and the Sorceress | Bryan Young |

As with all good heroes, Pip does not shrink from danger and adventure. Still, there are times when it would be good to relax at home. But Pip is far from home, and is searching for a powerful sorceress who can help him on his way. |

| 17 | January 14, 2026 | Terror Above Icehenge | Malcolm T. North |

To reach her, however, he’ll have to venture through the Chaos Realm and, as every true hero knows if you undertake that journey lightly, it will end quickly. But Pip has no choice, and therein our adventure begins. |

| 16 | December 31, 2025 | Demonfire: A Tale of Shintaro Oba | C. L. Werner |

A forbidden ritual conducted in secret, bathed in blood and death enables a demon to grasp unimaginable power—the power to destroy all enemies and raise himself above all others. |

| 15 | December 24, 2025 | In The Land of the Giants, | Bryan Young |

A Samurai, whose duty calls for him to hunt down such a creature. A destiny he must pursue even as the world burns around him. |

| 14 | December 10, 2025 | Blight | Katherine Monasterio | Forest Ranger Hazel Boncliff is a Green Speaker, a person with the magical ability to commune with plants. When the king summons Hazel and her assistant to the capital to heal the strange blight affecting his hunting grounds, she’s reluctant to help—least of all because he’s insisting his inexperienced secretary go along for the journey. But with a reward she can’t refuse and the blight’s effects more harrowing by the moment, she’ll take all the help she can get. |

| 13 | November 26, 2025 | Ice Hawk’s Aerie | Bryan Young | A chance meeting in the dark forest. A tale of woe and injustice. Pip Strongpaw, the last of the fabled Great Catriders, must once again wield the runed-sword Feathersbane, to end the chilling menace threatening to destroy the hamlet of Riveroak. A menace of sorcerous origins against which even the bravest of heroes may not prevail. |

| 12 | November 12, 2025 | Blood for the River | Michael Stackpole | Chased into a swamp by homicidal cultists, Kellach and Serinna encounter a fire mage who saves their lives, and then leads them on an adventure that is sure to get them killed. |

| 11 | October 14, 2025 | Of Nightmares & Jewels | Robert Greenberger | Something drew the mage onward, always toward the northwest, through restless evenings and dark dreams of ill portent. Yet when Jareth’s traveling companion, the swordswoman Talin, asks him why, he has no idea. And then they reached a tiny town at the edge of nowhere, wherein lurked an evil with roots sunk deep in times beyond remembering; an evil that has chosen their visit as a time to awaken. |

| 10 | October 14, 2025 | The Cursed Cuff | Aaron Rosenberg | She came to them spinning a tale of woe. An army of undead lay siege to the Manor she called home. She had barely escaped and sough adventurers brave enough to free her people. But to do that Birr Blackjaw and his companions would have to wrest an ancient artifact from the hands of a cult leader who had his own army, and a hellish pet none could hope to defeat. |

| 9 | October 1, 2025 | The Monastery Plot | Bryan Young | Shield Maiden and legendary sleuth Sister Agatha, accompanied by her faithful initiate, Brother Dominguez, sought to enjoy peace and quiet at the Monastery of St. Maryam.Despite their desires, they soon find themselves investigating twin murders. Murders which become all that much more bizarre when the name Tarru-Syn turns up, and their search leads them into the very bowels of the earth, to face a foe from beyond their reality. |

| 8 | September 24, 2025 | On Memories | Michael Stackpole | Dancillius Hrekt is fairly new to the world of Monster Fighting. All he wants to do is to make a good impression with his peers. And all they want is for him and his best friend to die. |

| 7 | September 10, 2025 | The Village of Morvoss | Thomas Grayfson | In this new Kavion adventure, our tormented knight clings to the last threads of family and sanity as he navigates the mysterious Village of Morvoss. Haunted by fractured memories, he must confront the darkness around him—and within. |

| 6 | August 27, 2025 | Fragment of a Sorcerous Crown | Joan Marie Verba | In this tale from the Chronicles of the Library of Sorcery, the sorcerers investigate a dangerous magical artifact of mysterious origin. Can the sorcerers uncover the truth?Sorcerer Serena is called to investigate an enormous, carnivorous plant. She finds that a mysterious magical artifact is behind the phenomenon. To find out where the artifact came from and what its properties might be, she consults the Library of Sorcery, where she uncovers the answers, but not on the Library shelves. Can the artifact be banished from the sorcerous regions before it becomes a more deathly threat? |

| 5 | August 13, 2025 | Grave’s Brood | S.E. Lindberg | Doktor Grave sends Brood to recover a crown from the Red Orchard, only for Brood to find it is the source of a bloody plague caused by Grave’s experiments. Facing vampiric plants and their loyal clan, Brood must confront his past and question whether he can trust Grave or escape the nightmare himself. |

| 4 | July 28, 2025 | Shard of Song | Rigel Ailur | Two wizards search desperately for a way to stave off a vicious magical-musical attack before the dragons succumb. A powerful relic ancient beyond memory calls to them, but do they dare use it? |

| 3 | July 16, 2025 | Forest of the Fallen Colossus | Bryan Young | A dying robber hands Laila and Zaki a mysterious artifact in the middle of a fae-haunted wood. “Danger,” the robber manages before dying. Suddenly sister and brother find themselves safeguarding an unwanted gift—on the run for their lives in the Forest of the Fallen Colossus. |

| 2 | July 3, 2025 | Death Grip | Michael Stackpole | The man hadn’t died easily.A smoking hole sat where his heart should have been. Terror twisted his features, and he clutched an emerald reeking of magick as if would somehow save him. Neryon and Magistrate-Martial Logan find themselves in a race to find the killer before he has a chance to harvest more victims. But, with the amount of power used on his first target, there was a big gulf between finding and stopping; and no guarantee he wouldn’t kill them, too. |

| 1 | July 3, 2025 | Blade of the Storm Witch | Robert E. Vardeman | Her vengeance became elemental! The Conqueror-King’s minion murdered her pirate husband. The Lady Rennata was condemned to follow him into a watery grave—until wind and wave swept her to a magical blade that commands all of Nature. |

S.E. Lindberg is a Managing Editor at Black Gate, regularly reviewing books and interviewing authors on the topic of “Beauty & Art in Weird-Fantasy Fiction.” He has taken lead roles organizing the Gen Con Writers’ Symposium (chairing it in 2023), is the lead moderator of the Goodreads Sword & Sorcery Group, and was an intern for Tales from the Magician’s Skull magazine. As for crafting stories, he has contributed eight entries across Perseid Press’s Heroes in Hell and Heroika series, and has an entry in Weirdbook Annual #3: Zombies. He independently publishes novels under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction; short stories of Dyscrasia Fiction have appeared in Whetstone Amateur S&S Magazine, Swords & Sorcery online magazine, Rogues In the House Podcast’s A Book of Blades Vol I & II, DMR’s Terra Incognita, the 9th issue of Tales From the Magician’s Skull, Savage Realms Magazine, and Michael Stackpole’s S&S Chain Story 2 Project.