Fiction Review: Infinite Crisis: The Novel by Greg Cox

A Review by D. K. Latta

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

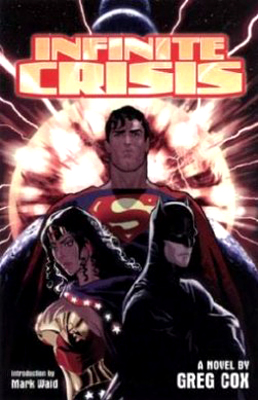

Infinite Crisis: The Novel

Greg Cox

Ace (384 pages, October 2006, $15.00)

Comic book heroes have occasionally made the jump to prose novels, but unlike when such properties are turned into Hollywood movies, where filmmakers liberally reinvent the source material, the novels are usually extensions of the mythos in the comics.

Occasionally, the plot itself is taken from the comics as well. Written by Greg Cox (no stranger to media tie-in projects, having written original novels derived from Iron Man to Star Trek), Infinite Crisis — featuring Superman, Batman, and the entirety of DC Comics’ fictional universe — is a novelization of a story first serialized in comics.

As such, it’s hard to decide who its target audience is. DC first tried such a novelization over a decade ago with The Death and Life of Superman by Roger Stern, adapting a story that had made headlines and was serialized in scores of different comics — as such it could be seen as being aimed at non-comics regulars, curious because of the press coverage, and comics fans who might find tracking down the relevant issues rather daunting.

But Infinite Crisis (the comic) was largely unremarked upon by the mainstream press, and was serialized over only seven issues (plus a few ancillary comics) — seven issues which themselves have been compiled in a collected edition.

As well, Infinite Crisis acts as the climactic final act to events that had been introduced in various earlier comics. There is plenty of recapping to get a new reader up to speed, but it still means the novel lacks a carefully established beginning. Imagine reading the Lord of the Rings…but starting with The Two Towers.

Still, it starts fast and furious with the mysterious destruction of the HQ of the Justice League (DC’s main super hero team/alliance). From there, threats manifest on various fronts, from a distant, intergalactic war, to a ruthless alliance of super-villains on earth, all part of a — literally — universe-shaking plan. Writer Greg Cox, adhering religiously to the source material, keeps the action level high. His prose style is clean with a kind of blunt efficiency that makes for an easy page turner, even as the metaphors and similes, when employed at all, are straightforward leaning toward clichéd. Cox tends to describe the scenes as they would appear in the comic, rather than embellishing them with non-visual descriptions (sounds, smells, sensations).

There is a fun aspect to it all, particularly for ex-comics readers who will derive a nostalgic thrill reading about characters with whom they haven’t visited for a while.

But it has a lot of weakness, too. This is meant to be a grandiose universe-shaking, epochal event involving almost the entirety of DC’s pantheon of heroes and villains. Characters die! New characters are introduced! Nothing will ever be the same!

Yadda yadda.

The problem is that DC churns out these sort of “must read” “never to be repeated” epochal events every year or so. From The Crisis on Infinite Earths, which largely begat the trend, to Legends, Millennium, Invasion, Zero Hour, Worlds at War, Obsidian Age and more. Infinite Crisis itself was sandwiched between Identity Crisis and 52 Weeks and One Year Later. The repetition rather mutes the effectiveness.

Granted, other than the apocryphal Kingdom Come, this is the first one novelized, so to non-comics regulars it’ll enjoy some novelty. But, like with most of the others, the very conceit — to involve all these heroes in a massive crisis — means much of the story is just a parade of semi-familiar (and some truly obscure) characters, most of whom have barely a line of dialogue — if that. A character appears, is given a paragraph or two explaining who he/she is — and often, just as quickly, disappears from the story.

Key heroes like Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman are featured prominently, and less famous characters like Power Girl and Animal Man (in a bit part) achieve a bit of an emotional connection with the reader, as does Dick Grayson, the original Robin, now called Nightwing, who has kind of become the heart and soul of the DC Universe (Frank Miller notwithstanding).

But the action is repetitive, as we cut from one group of characters mindlessly battling each other to another group of characters battling, in scenes that often seem to have little connection or relevance to each other (much of the mayhem is simply to distract the heroes from the real crisis). And the plot is a bit jerky and ill-explained, as characters come and go, or reappear with new costumes that are never satisfactorily explained.

Because this is supposed to have lasting repercussions, characters get killed — it’s mainly house cleaning as many are fairly obscure, or are killed simply to make way for a new character. We’re supposed to be moved by such deaths…but how do you decide who to mourn for when characters are being killed sometimes two or three per scene? And how do you weigh such deaths in a story where whole planets are obliterated?

Part of the impetus for this story was that comics had become increasingly dark and nihilistic, where even the heroes weren’t always acting like heroes. Infinite Crisis seems to be addressing that, as the heroes themselves realize things have gotten out of control. Except as the story unfolds (without giving too much away) most of those lamenting the loss of innocence are cast in, well, less than flattering light. And the story is chock full of characters getting their heads ripped off, having fists punched through chests, torn to pieces by cosmic forces…and subjected to the occasional acid spray.

Despite Mark Waid’s introduction heralding this as a refutation of the “grim and gritty” trend, the true message is: DC is quite happy with the vicious creative tone of its current line and isn’t about to change, thankee very much.

And there are a few dangling subplots by the end with characters whose fates remain unclear, presumably to be followed up on in the pages of other comics.

Those familiar with super heroes only through movies will probably find the parade of characters bewildering and the endless descriptions of the bizarre back stories kind of silly, while ex-fans might enjoy the nostalgia of revisiting their old heroes, though even they are liable to be confused by the changes and alterations many have undergone. Cox hasn’t necessarily embellished the material enough to make this an essential addition for those who’ve read the original comics. Sometimes a picture really is worth a thousand words.

At times a fun, briskly-paced romp, the story can also be rather thin and repetitive, relying too much on extended fight scenes and violence.

Infinite Crisis (mildly) resets the bar for the DC Universe, and for those curious to keep abreast of their heroes, it might warrant a look. For old time fans (like yours truly) the story re-acknowledges some of DC’s older continuity and even seems to reintroduce concepts that had been written out a decade or two ago. But it probably won’t be long before the next big “event” comes along, and Infinite Crisis will become as seminal as, say, your old copies of It! the Living Colossus.