Special Fiction Feature: “Iron Joan”

By ElizaBeth Gilligan

Illustrated by Chris Pepper

This is a Special Presentation of a complete work of fiction which originally appeared in Black Gate 3. It appears with the permission of ElizaBeth Gilligan and New Epoch Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2001 by New Epoch Press.

Joan came to our village a hardy, unsmiling woman of no more than seventeen, young even for our folks to be setting up house. That brute of a man, Thomas Murfie, brought her… her and her round-cheeked Baby John.

Joan came to our village a hardy, unsmiling woman of no more than seventeen, young even for our folks to be setting up house. That brute of a man, Thomas Murfie, brought her… her and her round-cheeked Baby John.

Even before Thomas bragged about her in the tavern, we knew who she was. He, a lowly sailor with never more than a copper to his name, had a woman of noble birth to set up his house and give him his children. What did he care if she came from a family marked as the devil’s own? That even with this birthright, she had been shamed? Who could have got that child on her? How had he dared? That Thomas showed no concern for the baby which was not his own seemed sign of witchery. Thomas Murfie wasn’t the sort who accepted another man’s spawn as if it were his own kith and kin.

Thomas took her straight to Pastor Matthew for the marriage blessings and after, before Pastor Matthew could offer her welcome, he packed her and her babe back into her rickety cart pulled by the sorriest nag this side of the grave anyone had ever seen. We watched her, that noble-born woman, daughter of the High Chief of Glen Cluain. She, who had been raised in luxury on the profit of her father’s robber baron ways, sat straight and stiff in that cart with wee Baby John on her knee. Thomas promptly left her at the shack she was meant to make a home and made his way to the tavern.

She sat for the longest time, still as stone, staring into the sea. We half-expected her to leap from the cliff. But after what seemed forever, she turned and surveyed her sorry patch of land and the shack that did no more than cut wind in a gale. With no one’s aid, she came down off her cart, put her infant in a basket cradle and began to unload the cart’s meager contents.

Where was the dowry of a High Chief’s daughter? She brought less to the marriage than a village girl; nothing more than a battered trunk, a squawking old hen, a bushel bag of potatoes, a half barrel of provisions and a flea-bitten bed roll.

Joan wasn’t a woman familiar with hard labor. Anyone could see that in the way she moved. Unloading the cart, however meager its contents, was man’s work, but she did it nonetheless. She never once looked back at the menfolk watching her from the village, though she surely must have felt the heat of our eyes. When the trunk slid onto her, not one of us heard a muttered oath. No. She stood rigid a moment before bending her back to work again.

She moved everything into the shack that afternoon and when she was done, she unhitched the horse and tethered it on a patch of winter grass near the house. Then, as she stood on the threshold of her new home, she stopped and turned. She looked each of us in the eye, over the distance of her rocky field before withdrawing into the shack.

Joan was the daughter of a High Chief, shamed by her father’s house, with a babe near a year old before any pastor said the marriage blessings over her, but her pride remained unbroken. She wasn’t humbled by the shack that replaced her father’s castle nor her ale-swilling husband. We knew the stories about evil magic in the high family of Glen Cluain. Some of us were fool enough to think we saw a hint of it in the unbending, silent stance of a fair-haired young woman that day.

Would that I could tell you we greeted Joan with pleasantries that first morning she came to the village; or the second or even a month of days later. We spoke to her when we were spoken to, then quickly turned our backs and whispered prayers to turn the evil eye.

She came early each day, Baby John perched upon her hip. From the Widow Turlough she bought milk for her baby, and oats from Miller Dunne for her nag. She paid with bright shiny pennies carried in her apron, then she would wish us a good day and begin her slow walk back to the shack.

Those first months, sometimes we would pause in our labors and look toward the shack by the cliff. We could see Joan grooming the remnants of the winter coat from her horse, or stringing a line behind the house to hang out her wash, all the while talking to Baby John. Thomas, we saw in the pub each night.

The day Joan came to the village with the marks of her husband’s fist on her face, we knew we’d seen the last of Thomas. Widow Turlough offered Joan a poultice then nearly died from fright when Joan’s face turned stony while she waited for her milk. That night Thomas Murfie was warming his normal seat at the pub.

The entire village breathed a sigh of relief that early spring morning two weeks later when Thomas’s ship sailed from the port at the county seat. Joan and Baby John watched the ship from the edge of the cliff then went back into her house.

Plowing and seeding time brought a new flurry of debate. It was the men’s duty to look out after the widows and lonely women, to see to it they had a crop to feed their families. For all of our God-fearing obligation, we couldn’t decide who would be the one to step forward. Joan, in her own silent way, ended the talk.

With Baby John settled in a basket nearby, Joan and her aging nag struggled with a make-shift plow through the rockiest patch of land inside County Ros. It was backbreaking man’s work, but the High Chief’s daughter had set her mind to it. She stopped every so often, whistling and clucking to the horse as she squatted down and dug through the soil with her bare hands to unearth the rocks that pitted her field. Stranger than a woman plowing that field by herself was what she did with the stones she came upon. She would loop a rope around the rock and drag it to cliff-side. There, between a craggy tree and the cliff, she set her stones. As the morning progressed, more of us hovered at village edge where we could watch her plow the field and build her coiling pattern of stones. If Joan saw us, and surely she must have, she pretended otherwise. Toward noon there was a jostling of elbows among the men as we encouraged one another to offer help. It was Widow Turlough’s half-daft son, William, who broke from his mother’s side and approached Joan at her plow. We all strained to hear what he said and, in turn, what she said to him, but they spoke softly. William nodded and trudged back over the field to us.

“What did she say, boy?” I asked.

William looked up in that dazed way of his and shrugged. “She says she’ll do for herself.”

Fear trembled the best of us then. Who among the highborn turned away service unless they were angry?

“What does she want of us?” Miller Dunne asked.

William squinted up at the miller’s puffy face and shook his head. “She says the field’s her own and the work’s her own.”

We turned to Pastor Matthew. “She’ll be cursin’ our names, Pastor. You have to do somethin’!” Farmer Brennan pleaded.

Matthew straightened his church smock and pressed back his wild red hair, then crossed the field to Joan’s side. She stopped her digging when he came upon her, cleaning her hands respectfully on her apron before she greeted him. She looked at us then, when Pastor Matthew spoke to her. She grew tall and stiff, her face more stony than ever before. She shook her head and watched Pastor Matthew until he reached us before turning back to her work.

We looked expectantly at the red-faced pastor. “She wishes us no ill and she will accept no help.” He stopped to take a deep breath. “She said that she will owe no man nor woman in this village.”

“Then the curse is upon us,” Widow Turlough moaned. “A witch cannot owe those she curses.”

Pastor Matthew held up his hands. “The woman claims she holds no ill against us. She says upon my very God’s cloth that there will be no curse.”

“But what nature of a woman wants no help in the field?” Miller Dunne asked.

Matthew shook his head. But I watched Joan, straight-backed stiff, whistle to her horse and push her plow on through her field.

“She’s made of iron, that one,” I said. The others nodded. No one doubted my judgment. And so it was that we came to call her Iron Joan in those days of plowing and seeding.

Overnight, someone left a decent plow by her doorstep … an offering to turn the curse. We watched her in the fields with that new plow and watched the pattern of rocks by the cliff take shape.

There was a time when it looked, from the village, as though she built a serpentine monster and the wind in the craggy tree looked to be its winking eye. She toiled on, ignoring those of us who watched her on those long miserable days, praying that she wasn’t planning her vengeance on us. Gradually, however, our fancy of fear was replaced by reason and the pile of rocks slowly turned into a house. We watched her after seeding time, when she packed mud between the rocks of that craggy house she built. We watched Daft William wander over one day before anyone could catch him and begin to work beside her.

We saw many things that spring — like her rooster-less hen followed by a trail of peeping, downy chicks and the nag begin to look like a glossy-coated young mare. Daft William brought her the blind runt from his bitch’s litter. When one of Farmer Brennan’s milk cows dried up, Iron Joan arrived on his doorstep with a handful of pennies, a bushel bag of potatoes and the rickety cart. Brennan sold her the cow and gave her its sickly calf for good measure. Like everything in Joan’s care, the calf grew hale and hardy and the cow gave milk.

Daft William crossed Joan’s field with impunity whenever he was lacking for work in his mother’s house. He would come away talking of Joan’s cooking and the stories she told of sleeping dragons who could be summoned if you knew the way. We couldn’t help but wonder at the strange friendship but none of us dared speak against it.

Joan’s house of stone continued to take shape and, even with her belly swelling with her second child, she refused all help but William’s. Offerings made in the night … hammer and some nails, strong timbers for beams … these were the only things she did not refuse. No one admitted to the offerings and certainly no one showed for lack of the items that appeared by Joan’s doorstep.

In the heat of one day, she broke down the shack her husband had given her and passed the boards up to Daft William to nail down as a frame for her roof. That night she and Baby John slept beneath the rickety roof, refusing even Pastor Matthew’s offer of a bed in the church. Morning brought sight of another anonymous offering: thatches for her roof.

Thomas Murfie returned from the sea mid-summer. We watched him carefully as he paused at village’s edge to stare at the wonderment of his wife’s work. A fine house had taken place of the shack; a well-groomed mare replaced the nag; and there were chickens, a cow and her calf, and a young dog who stood at his mistress’s side with his lip half-curled back. Baby John wore toddler’s clothes and hid from Thomas among his mother’s skirts.

We waited with great anticipation in the pub, coins already pressed into Angus’ hand to pay for the rounds of ale that would loosen Thomas’ lips. But Thomas was brooding and sullen, silent in his cups. Well past time for the more sensible among us to be in bed, he shambled back to his wife’s house with hardly a word spoken. There was a glint in his eye that did not bode well for Joan. Some among us considered waylaying him, but in the end, fear held us.

We were unsurprised to see Joan moving stiffly about her chores the next morning and none among us were without shame for having done nothing. But what were we to say to Thomas Murfie? And would the Iron Joan we grudgingly admired have accepted our interference?

Mercifully, Thomas’ stay from the sea was brief. He set out for the port at the county seat with his pay still in his pockets, leaving his wife to make due with whatever she had. The day his ship set out to sea, she stood with Baby John in her arms on the edge of the cliff, watching.

When Finna Brennan’s time came early that fall, my Grania, the village midwife, was called to her side. It was a gray day, made worse by the signs that Brennan’s wife was going to bring forth another stillborn child, only this time she seemed likely to die with it. Pastor Matthew and I stayed with Brennan, trying to distract him from the sounds in the house. Late in the day, Grania called Pastor Matthew inside. We saw the news on his face when he returned.

“I’ve done what I could,” he said.

Brennan sank to the ground, leaving me to ask, “Is there nothing anyone can do?”

“She wants the witch. She says only the witch can save her and the baby,” Pastor Matthew said.

“The witch’s curse caused this!” Brennan said.

Pastor Matthew shook his head, but kept his own council.

“Let’s see what Iron Joan can do,” I said.

So it was I who set out to her stone house. Despite the wind, her door was open. I smelled fresh baked bread and heard John and William laughing. From the shadows of her house, I heard Joan’s steely soft voice speak to me.

“Come, Smithy Kerwin. Warm yourself by the fire and have some tea to warm your bones.” She came forward into the light then and I could see her own time was near.

“I’ve come … Pastor Matthew sent — ”

“Finna Brennan’s time has come then, has it?” she said, reaching for the shawl by her door. “William, bring the boy.”

I followed her with William beside me carrying John. None of us spoke during the strange march to the Brennan farm. It frightened me how she saw me by her door before I was there and how she knew my purpose. William caught my gaze and laughed, bouncing John into the air.

Farmer Brennan hovered near the door of his house like an angry bee. As Joan stepped up, he pulled away from Pastor Matthew and blocked her way. “Let no harm come to my Finna, Witch! I know you for what you are — ”

“Enough!” Matthew said, taking hold of Brennan’s arm.

Joan went directly to the birthing room but paused at the door. The silence that followed seemed to stretch into forever … then she spoke.

“There is no laughter in this house, Finna, and that is why your children die!” She came into the main room and looked at us sternly. “Why is there no laughter in this house, Brennan? You have a good wife and a fine farm. Open your windows! William, show these men how to laugh!”

“She’s as daft as William!” Brennan growled, rising.

Our Joan met him, her face grim as she stared into his eyes … and big man that he was, Farmer Brennan knew enough to recognize his better. “Welcome this child with laughter, Brennan, and make his days sweet and you will have a fine healthy son; but raise your hand to me, the child or the wife and never will you have a family to gather at your hearth!”

We were silent, staring at Brennan and waiting. He crumpled into his chair, shaking his head mournfully.

“John!” she said and held out her arms. Her boy ran to her laughing, then William rolled his head back and let out such a guffaw I thought the roof would come down on us. The pastor’s rich chuckle rumbled from deep within him and, God help me, even I began to laugh until the tears ran from my eyes. Grania came to the door, confusion on her face, and suddenly she was laughing too. Brennan began to shake and the first laugh came out like a croak, an odd sound at best, then he sat back and let the laughter out.

Joan watched us, that stony stoic mask never once twitched, then she set her boy down and went in to Finna. It seemed but a moment more before she brought out the baby.

Brennan held the boy in his arms and the laughter stilled for a moment as he stared in wonderment at the child, then he threw back his head and laughed like he would never stop.

When the women’s business was done, I went with Joan and her boy and William back to the stone house. I’m not sure why I went, but I did. John toddled chortling at his mother’s heels while William grinned at me and tossed rocks over his shoulder. As we neared Joan’s house, I asked about the laughter.

Iron Joan paused in the doorway, ruffling John’s hair as he ran inside. “I grew up in a house with a man who’s very breath was a scourge. There was no laughter in his house either. I have John because I promised to give him a home with laughter in it.”

“But laughter — ?”

She stared at me in her stiff way. “Believe as you please, Smithy Kerwin.”

William came for Grania when Joan’s time came. We watched my wife make her way along the road, following in Daft William’s footsteps that warm fall day.

Somehow, we were all about the village square late into the evening when Grania returned. Had we doubted she would come back? Did we expect news of some demon child borne of Iron Joan? Grania told us only that Joan’s child was a girl named Saraid then shut me out of my house for the night.

William, with his mother’s leave, started the harvest of Joan’s crops the next day. Farmer Brennan left his family and crops to join him. By noon, Joan was working beside them with her newborn daughter asleep in the basket cradle nearby.

Thomas Murfie came home from the sea in early winter. Neither his new daughter, nor his wife’s labors seemed to please him overly much. We waited of an evening in the pub, hoping that he might speak of Iron Joan’s secrets, but the garrulous braggart who brought her to us nursed the ales we bought him with barely a word of thanks and nary a murmur of conversation.

The winter was long and hard. We spent hours watching the stone house, wondering what happened there. It seemed Thomas, though he had grown sullen and silent, still did not hesitate to raise a hand to his wife, perhaps to punish her for giving some other man a son and him only a daughter.

We could see Joan about her chores stiffer than even the cold and her straight-backed way called for. What man sired Joan’s son and could be worse than the brute she married that she would let Thomas treat her so? We grew less and less interested in anything he might tell us and, soon enough, Thomas was paying for his own drinks.

None of us were sad to see the back of Thomas Murfie that spring morning he headed off to the county seat. His wife stood on that same cliff, watching the ship sail by, with sturdy John beside her and fair Saraid in her arms, her belly already swollen with another child.

The second year went much as the first. She plowed her own field, but this time young John seeded the soil behind her. Her cow calved two fine bull calves, though it was a mystery when or how the cow had been bred. The dog scattered even more chickens and chicks in his wake through Joan’s yard than any of us could count. Then Farmer Brennan, with young Luke astride his shoulders, brought her two ewes near lambing time. We watched from the village as she refused the gifts at first, but after Brennan said something else, she opened her gate and let the sheep onto her land.

We stopped Brennan on his way home and asked about his gift to Joan.

“‘Twas no gift. Those two were blighted from first breech lambing. I’ve enough to busy my hands without those two.” But I saw him wink as he turned, swinging Luke onto his shoulders again.

So it was that Joan’s small farm prospered. The village children didn’t fear her as their parents did. Many a morning, we would spot a child scamper between the fence posts and up to the stone house. Only the Widow Turlough was willing to go after William and when she did, the other children came running back, laughing and talking about the wondrous stories of magic and dragons Iron Joan told.

Moira and Mahon were born to Joan early that summer, long weeks before they were expected. But nothing ever seemed to whither or fail in Joan’s home and so it was that they were strong sturdy babes when Thomas Murfie found his way home in the late weeks of summer. Neither the riches of the farm nor chuckling twin babes — even one a son — pleased him; so, sour and sullen, Thomas languished his evenings in the pub. Joan was stiff from his beatings when she stood with her children upon the cliff and watched his ship pass out into the sea.

Come fall, Brennan and William took one of Joan’s bulls to market in the county seat. She and her children harvested and stored the fruit of her field without aid. When Thomas returned from the sea in the early winter, Joan met him at the gate. We watched as he raised his hand. We watched Joan lift her chin and fix him with her stoic gaze. Thomas Murfie dropped his hand and Iron Joan opened the gate for her husband.

So it was that years began to pass and Joan’s family prospered and grew as readily as her small farm. In ten short years, she bore seven more children: Shonna, Brendan, Colum, Myles, Kaitlin, Una and Ronan; and, though she still made us uneasy with her stiff, unsmiling ways, we learned to trust her.

We thought it odd that midsummer’s day when the rider, wearing the colors of Glen Cluain, came to the village and demanded to know where he could find Joan of the High Clan Cluain. So many years had passed since we thought of our Joan as a member of her accursed father’s family that Miller Dunne was speechless with confusion. It was Pastor Matthew who caught the rider’s fist when he would have struck the miller and I who stepped forward and asked him why he looked for her.

“I come in her father’s name!” the rider snarled.

Thirteen year old Saraid spoke with that soft steely voice so like her mother’s, “Come down off your horse then, Sir, and pray let him rest. You may come with me to my mother’s house.”

The rider turned a hard eye on the blonde girl and apparently saw enough of Joan in her that he dismounted and followed her to the stone house with its craggy tree by the sea.

As had long been our habit, we watched our Joan come from her house with young, strapping John hard on her heels. If it was possible, she stood stiffer and straighter than we’d ever seen and her face, always stoic and cool, seemed to be frozen like a cold winter morning. She opened her fence just wide enough for Saraid to enter, but snapped it shut so that her father’s rider could not follow. Strange behavior, indeed, for the woman known for having the warmest and most welcoming hearth in the village. She shook her head and spoke quietly to the rider who grew angrier and louder by the moment. Twice Joan stopped John from stepping forward and gestured for the rider to leave.

I went to my forge for my hammer and found, upon my return, that I was not the only man in our village prepared to defend Joan from this armed rider. We would even risk a raid from Clan Cluain. She looked toward us as we approached, I with my hammer, Farmer Brennan and his son with their staves. A score of others stood behind us. The rider turned and saw us too. He said something more, quietly, harshly, so that we could not hear him, then mounted and rode away. Joan nodded to us then returned to her house.

We were not pleased when the second rider came the following week, but he came from the direction of the county seat and seemed friendly enough when he asked for Joan Murfie. I pointed the way, but kept a wary eye turned in the direction of the stone house. Young John greeted the rider at the gate, pitchfork in hand, and, after a time, opened the fence to let the rider in.

Dunne came from his mill and Matthew from the church. We found ourselves at our watch posts when Joan came from her house and welcomed the rider inside. We talked, the pastor, the miller and myself, about our prospects come fall, then the weather, and finally our musings about the riders.

Late in the afternoon, the rider paused by the mill pond, long enough for his horse to drink and for us to join him.

Matthew caught the horse’s reins and idly stroked its head. “Greetings,” he said.

“And to you, sirs,” the rider said warily. He fidgeted with the reins.

“What brings you looking for Joan Murfie?” I asked and patted the horse’s flank.

He started. “I came to bring news of Thomas Murfie’s death. He — he died last night. A man — A stranger gave me coins to bring her the news.”

“Was the man dressed in red? Did he bear the arms of Glen Cluain?” Pastor Matthew asked.

The rider nodded and turned his horse abruptly back to the road as soon as Matthew freed the reins. We considered one another quietly. Evil, a long time forming, had come to roost in our village, at our Joan’s doorstep.

So it was a week later that Luke Brennan sat idly by the south road instead of tending his father’s flocks. He brought news of the riders a full hour before they reached the village and we were ready for them, or so we thought.

We heard the riders before we saw them, the chinking and creaking of their saddles and armor, the stamping of their war horses’ hooves. Every last one of us filled the village square. We tried to seem unafraid of the High Chief of Glen Cluain and his entourage of warriors and fine ladies. We were blinded by the gleaming brilliance of the war band’s armor and the richness of their ladies’ dress.

A man of such immenseness that even I felt runted before him, dismounted and pushed between the snapping and snarling war dogs. He stood before me all tall and bold, smelling of sweat and sweet herbs. He was fair, with hair like bleached flax. It seemed impossible to guess his age until I looked into his hard gray eyes. His eyes and the twist of his lips showed him as old and soulless as the demon he was told to be.

He, the demon-chief, slowly pulled off his scarlet-trimmed black leather gloves and slapped them against his blood red tabbard. “Smithy,” he said as he stared down at me, “your people have blocked the road.”

I did not speak, could not speak, for my very throat seemed to have frozen. His voice was soft steel, like his daughter’s.

He turned abruptly and remounted. “I give you one last chance to make way before I set the dogs on you.”

I felt a tug on my sleeve. Daft William stood beside me so I leaned over to hear him. “She says to let him pass. You must not do this.”

Others also heard William. There was grumbling; we were prepared — finally — to help Iron Joan and now we didn’t want to be found lacking as staunch allies.

“She says you must not stop him,” William insisted.

“But we want — ” Pastor Matthew began.

William shook his head. “Don’t you see? You cannot fight her father … only she can. Now, if only now, you must respect her enough to stand aside.”

I glanced back at the High Chief of Glen Cluain. For so many years, I’d thought Thomas Murfie a brute of a man, but now I saw him for the sniveling cur he was beside this man who was Joan’s father. Now I understood how she endured Thomas for so long before she changed him.

“Step aside,” I said quietly. The villagers did as I said, leaving me alone in the path of the High Chief and his riders. “You’ll find our Joan up the road in the stone house. She’s waiting for you.” Then I, too, stepped aside, barely dodging the flailing hooves of the High Chief’s horse.

We found our watch posts easily enough and peered hard through the dust flung up by the riders. When the dust settled, I could see Joan standing outside her house with her children behind her. I couldn’t hear what she said, nor her father’s reply, so I climbed down from the fence and walked a piece up the road barely aware of the others close behind me. I stopped in the shade of a tree. I was close enough now to hear and see everything.

The High Chief leaned against his saddle horn, a picture of complacent indifference, but still, there was an energy about him that gnawed like a terror-stricken rat at my gut. “I’ve come for the boy, Joan,” the High Chief said. He gestured with his glove at the tallest of Joan’s fair-haired brood, young John.

John shifted behind his mother, but stilled when she shook her head. “My John stays with me,” Joan said. She stood braced and ready.

We watched her father, the villagers, the warband and their ladies. The High Chief flicked at a fly with his gloves then motioned to his daughter and her brood. “You’re my daughter and as such of the High Clan of Glen Cluain. Widowed and your children orphaned, of course, you must turn to your kinsmen for succor.”

“I ask nothing from the Clan,” Joan said. “It has been my prayer for many a year now that if my kinsmen looked upon me they would see neither kith nor kin.”

The High Chief straightened on his charger, as stiff and stern as his daughter had ever been. “Your tongue hasn’t dulled these many years, Joan. We offer you kindness and comfort and you give us a full measure of your temper. Is there so little gratitude in you?” His voice had a lethal softness that stole over the gathering like a smothering quilt.

Our Joan stood staunchly. “Gratitude, Father? You offer me nothing I would thank you for.”

“I would bring you and your children to the seat of Glen Cluain. Your very own children would stand in line to take my throne when I relinquish it! I’d have your children know the riches of being sons and daughters of the High Clan of Glen Cluain, inheritors of a king’s fortune and members of a warrior’s family.” His voice was softer now, coaxing, but his bearing was that of someone willing to take a treasure by force.

She trembled, as she placed herself squarely between her children and father, and for that I hated the High Chief even more. “They would inherit a fortune stolen from the humbler people of three counties. They would be branded thieves and murderers as you and your mighty warband have been.” She shook her head. “No, Father, you’ll not have me nor my children.” She squinted up at him then, her voice as frigid as ice. “I know that I hold no great charm for you and neither do ten of my children. No, Father, let it be known that you have come for my eldest, our own son, John — ”

“Have a care, daughter! Your tongue has gotten you in trouble before!” the High Chief snarled at her. His horse reared and pawed the air. I held my breath, fearing Joan might be hurt but she seemed all too skilled at avoiding a warhorse’s hooves and came to no harm.

Joan looked at her father’s riders and then back at us. “Do you think you can still shame me to silence, Father?” She crossed her arms and stood her ground. “You branded me seductress and whore in your house when your second queen found you in my bed.” She ignored his thunderous demand for her silence as she continued, her words spilling out in an unstoppable flow. “I was shamed before the clan you would have me show gratitude to and cast out with little more than the clothes on my back. So, now that your queen cannot whelp you a son, you take more interest in the boy you got on me.”

“Enough!” the Chief commanded. “This talk is not meant for open company!”

Iron Joan turned and looked at us — at me — as though judging her revelations’ effect. I did not turn away. These many long years she had worked to become one of our own and I would not deny her her just earned respect.

“You can no longer silence me, Father!” She looked at the riders behind her father. They would not meet her gaze. She spat on the ground in front of them. “You shamed and shunned me, knowing what he’d done! You follow him like dogs to your deaths!”

“You’ve gone mad,” the High Chief declared.

Iron Joan smiled. The first I’d ever seen from her. There was power in that expression. A power that seemed to wash over her.

Daft William tapped my arm and pointed toward the stone house. “See! She has summoned her dragon!” he whispered.

I squinted down at him, sure that he was mad. He pointed insistently and I could not help but look. At first, I did not see it, then, as I was about to call him a fool, I caught the suggestion of a great scaly back in the stone house. As it had in those early days of building, a monstrous shape could almost be seen — if you looked for it, if you believed in such things. The craggy tree which seemed to extend from within the house was a long neck. A great wind swept in from the sea, billowing the cloaks of the High Chief’s riders and rattling the upper branches of the tree as it shifted and contorted … like a mighty dragon stirring from a long slumber.

“Do you think I didn’t know Thomas took your gold in those early years? So that you might know what became of me? So that I might be indebted to you?”

“Hold your tongue! Have you no respect — ” her father began, glaring angrily at those who stood to witness his evil revealed.

“Respect, Father? What should I respect?” Her rage was in full bloom. Around her, winds billowed and small stones in the house began to shift as if the dragon continued to stir, restless in his sleep. “I grew up fearing you. I tried to love you and honor you as a daughter should. Did you respect my gift? No, like anything in your house, it was trod beneath your boot. When my mother could no longer get you an heir, you called her a witch and let her burn at the stake. You left me in the hands of kinsmen who feared me because I was my mother’s daughter while you attacked innocents, taking what you wanted and leaving ruin in your wake. Anything that lived wilted at your touch. Your legacy is death, chaos and grief!”

“And what have you to show for your life, Joan? Eleven brats? A drunkard husband? A patch of land no bigger than my barn! You shame yourself and your children, revealing yourself as you have!” the High Chief spat.

The wind buffeted Iron Joan’s thin body as she gathered her children to her. The sky roiled with sudden dark clouds. A thatch loosed itself from her roof and scattered in the faces of the demon-chief and his subjects. The dragon shape shifted. Was that a blinking eye? Or only branches tossing in the wind?

With her arms around her children, Joan turned to her father. “You have sewn hatred and poison that taints all you touch. For every coin you stole, I sewed a seed. For every murder, I have brought healing,” she said. She turned her face into the rain as it began to fall. “Tears from heaven, Father.”

We stood there, in the rain, waiting for Joan’s father to speak … for his warband or one of their ladies to do something. The rain fell, soaking us to our skin, and still everyone waited and watched. Then, the youngest, the lowliest of the High Chief’s band turned his horse toward home. Without a word, others followed. The High Chief sat rigid in his saddle only turning to stare at his company of riders as the last of them left.

We stood there, in the rain, waiting for Joan’s father to speak … for his warband or one of their ladies to do something. The rain fell, soaking us to our skin, and still everyone waited and watched. Then, the youngest, the lowliest of the High Chief’s band turned his horse toward home. Without a word, others followed. The High Chief sat rigid in his saddle only turning to stare at his company of riders as the last of them left.

He sat there, astride his horse, stiff and silent for the longest time. When he spoke, he nearly erupted from his saddle as he spewed his anger and humiliation. “You have brought a shame that will never heal upon my house!” He pulled his mighty sword and raised it over his head.

Lightning flashed. I glanced back and saw that only Daft William, Farmer Brennan, Pastor Matthew and I remained to witness the end. I pointed towards the war-chief and yelled through the storm that we should do something. Matthew shook his head and pointed. I looked back at Joan, her children behind her, as she stared up at her father. A strange expression creased her face and then she laughed — a free and unfettered laugh that rang with power.

“It wakes!” William said excitedly, pointing at the house.

The stones that were once Iron Joan’s house were now clearly the pebbly scales of a craggy necked dragon. It swung its mighty tree-like head as though summoned by the bell-like laughter of our Joan. The High Chief spurred his warhorse toward his daughter and swung his great sword in what was surely meant to be a killing blow. Instead of striking Joan, the sword bit into the rocky flank of the thundering beast and there it stayed. The wind howled round the monster as it seized the armored man off his steed and into its great maw.

Thunder clapped and a second bolt of lightning cut through the sky. The storm rolled overhead and spewed fist-sized hailstones at us, forcing us to duck low to protect ourselves. Even through the deafening storm, we heard a scream of such mortal terror that behind me, Pastor Matthew whispered a prayer. I could only hold my breath. Then, just as it began, the storm was over.

We waited a long moment, crouched beside the fence. Somewhere a bird sang and Grania called from the forge. We looked to the village as our neighbors came from their houses. We looked slowly toward the stone house, half-expecting to see a rocky, scaled dragon, but all was normal.

Young John was already clambering up to the roof to fasten down the fly away thatches and the younger children were herding the animals toward their pens.

I stood beside Pastor Matthew and Farmer Brennan and stared at the farm. Had I imagined it? Then Iron Joan met my eye, stared me full in the face and smiled a slow, warm sunny grin as she gathered up her youngest and went into her house.

I looked to my neighbors, but they seemed as confused as I, until William tugged at my sleeve. We looked to where he pointed. There, in the tree, sticking out of the wood as if it grew there, was a scarlet and black leather glove … and above it, in the branches, a bit of shiny metal winked in the sun.

Years later, as visitors speculate over the mysterious disappearance of the High Chief of Glen Cluain, I stand away from my forge and listen … for the sound of a woman’s laughter coming from a stone house by the cliff.

By The Same Author

By The Same Author

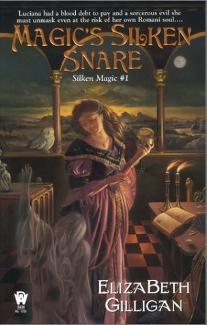

Magic’s Silken Snare

Silken Magic #1 (DAW, April 1 03, 556 pg)

ElizaBeth Gilligan’s first novel opens the Silken Magic saga, set in 17th-century Sicily — and a mythical kingdom across the water known as Tyrrhia. It is a world in which magic has the power to shape the course of history… and love has the power to unravel it. Where religions rise, governments fall, and the only thing more powerful than a Gypsy’s passion… is a Gypsy’s curse. It is on sale April 1st, 2003.

One thought on “Special Fiction Feature: “Iron Joan””