The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Location, location, location…that might have been Clark Ashton Smith’s motto for fantasy writing. Where most continuing fantasy sagas center on the adventures of specific heroes, such as Conan, Tarzan, and Imaro, Smith elevated milieu over character. Smith’s dark ironies and bleak fates made continuing characters unlikely, and his writing style cleaved more to the sensations a setting could evoke than the deeds of the people within it.

Location, location, location…that might have been Clark Ashton Smith’s motto for fantasy writing. Where most continuing fantasy sagas center on the adventures of specific heroes, such as Conan, Tarzan, and Imaro, Smith elevated milieu over character. Smith’s dark ironies and bleak fates made continuing characters unlikely, and his writing style cleaved more to the sensations a setting could evoke than the deeds of the people within it.

The lands of Averoigne, Hyperborea, and Zothique comprise the bulk of the Northern Californian author’s fantasy stories, but a few “mini-cycles” of two to five tales each also emerged during his most active period of fiction-writing in the early 1930s. Smith may have planned to expand these series into full cycles large enough for book publication, as he attempted with Zothique and Hyperborea. Internal references in this handful of tales, such as the recurring figure of Malygris in the Poseidonis stories and Maal Dweb in both Xiccarph chronicles, indicate that their creator was attempting to weave a unified backdrop for further works — except that the later works never emerged.

The three most important mini-cycles occur on a remnant of sinking Atlantis called Poseidonis, a human-colonized Mars containing ancient horrors from its primordial past, and the mysterious planet of Xiccarph. The Poseidonis stories resemble the style of the Zothique cycle in their doomed terrestrial environment. The other two mini-cycles take place in interplanetary settings that would normally fall under the aegis of science fiction. Smith did pen a number of straight science-fiction works like “The Master of the Asteroid” and “An Adventure in Futurity,” but the tales of Mars and Xiccarph have more in common with dark fantasy than the space opera of the early 1930s. Smith’s adept melding of science fiction, fantasy, and horror in these two planetary settings offers a fascinating view of his genre-blurring style.

Smith’s attitude toward science fiction made this blend natural for him, as he mentioned in a short essay published in 1973:

Science has discovered, and will continue to discover, an enormous amount of relative data; but there will always remain an illimitable residue of the undiscovered and the unknown. And the field for imaginative fiction, both scientific and non-scientific, is, it seems to me, wholly inexhaustible.

Smith’s science fiction leans toward the “undiscovered and unknown” instead of what he termed “the modern more materialistic science,” pushing his stories into the realm of the fantastic. Xiccarph and his vision of Mars could possibly exist within the boundaries of hypothetical science, but they exude the wonder and mystification of fantasy and the chill touch of supernatural horror.

Smith’s continuing focus on Zothique followed by his sudden departure from fiction writing in 1934 (he would return sporadically to the form until his death in 1961) aborted these series before they could properly begin. What exists of these abbreviated sagas contains some of Clark Ashton Smith’s finest prose work, but it also leaves a residue of the frustration of unfulfilled potential. What other wonders might High Priest Klarkash-Ton achieved with the weird worlds of Xiccarph, ancient Mars, and drowning Poseidonis?

Poseidonis

Poseidonis

Atlantis towers as one of humanity’s grand legends, a myth that has evolved into a cornerstone of storytelling, folklore, and metaphor. Originally created as a philosophic example for two of Plato’s dialogues, the Timaeus and the Critias, Atlantis really emerged as a contemporary myth/fantasy milieu/conspiracy theory/New Age cynosure because of two eccentric nineteenth-century individuals: Minnesota Congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly and Theosophical Society founder Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Donnelly’s popular 1875 work of pseudo-science, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, proposed that Atlantis existed as more than a philosophical metaphor and could have sunk as Plato claimed and theorized that the lost continent explains anomalous commonalities between disparate world cultures. Blavatsky took the mystical path, suggesting in her books Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine that Atlantis was a cultural exemplar and home to the fourth “Root Race” that was destroyed through black magic.

Regardless of what later writers have thought of the veracity of Blavatsky’s and Donnelly’s claims (scientists and anthropologists have debunked Donnelly since his first publication, and Clark Ashton Smith dismissed outright the pan-religious teachings of Theosophy), they did embrace the concept of the ancient continent as these two imaginative trailblazers re-envisioned it. From hard science-fiction novels to ethereal fantasies, Atlantis has turned into a tabula rasa of speculative fiction: it can be anything a writer desires it to be.

Clark Ashton Smith could hardly let his pen pass up a vanished continent rife with sorcerous potential. As he mentioned in a letter to H. P. Lovecraft in May 1932, the fantasy backdrop Blavatsky created in Theosophy had a direct influence on the creation of a number of his fantastic settings, like his Hyperborean cycle and references to Mu and Lemuria in stories such as “An Offering to the Moon” and “The Epiphany of Death.” But except for a few poems, Smith didn’t approach Atlantis as an entire continent. Befitting his love of cultures in decline, he wrote about Atlantis in its death-throes, reduced to a final splotch of land that Blavatsky called Poseidonis, which according to Theosophical doctrine sank in 9,564 B.C.E. (Beware of exact numbers, Helena.) The idea that Atlantis submerged not in a single cataclysm but over an extended period comes from Theosophy and not any source connected to Plato.

Mentions of Hyperborean lore in “The Double Shadow” indicate that Smith intended Poseidonis to postdate the destruction of his version of Hyperborea. The people of this Poseidonis fit with Blavatsky’s controversial racial theory that the Atlanteans were the root of an “Aryan” race. Smith describes the high Atlanteans as people of “fair complexions and lofty stature, with the features of a lineage both aristocratic and knowledgeable.” There are few geographical hints about Poseidonis in the story, although the two most important cities are the capital Susran and the port city of Lephara.

Despite its storytelling potential, Smith finished only four stories about Poseidonis, plus a peripheral work in an historical setting. His notes indicate that he planned at least two more Poseidonis entries before his first phase of fiction-writing ended in 1934. He never returned to the foundering island in his later periods of productivity.

I have listed the stories in the order of composition as near as it can be ascertained. Lin Carter in his Ballantine Adult Fantasy collection Poseidonis arranged them by internal chronology, slotting “The Double Shadow” after the two Malygris stories, concluding with “A Voyage to Sfanomoë,” and adding “A Vintage from Atlantis” as a sort of epilogue. As with the other articles in this series, I have worked from the stance that a better understanding of Smith’s writing comes from viewing his work in order of composition.

“The Last Incantation”

“The Last Incantation”

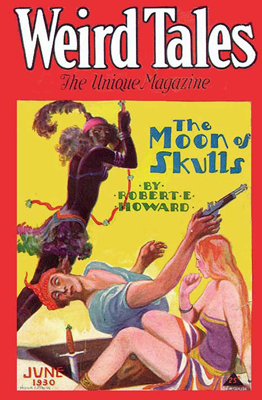

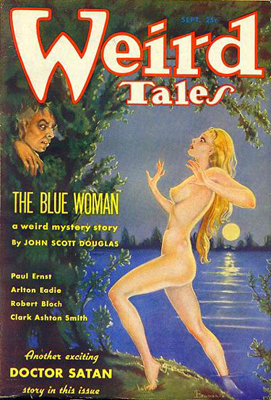

Completed September 1929. First published in Weird Tales, June 1930.

This is one of the earliest works from Smith’s productive five-year period of short-story writing. It is the second story logged in the “Black Book” where he maintained a record of his fiction. “The Last Incantation” is a nearly plotless sketch, but contains an emotional coda that even readers unaccustomed to Smith’s Byzantine style can appreciate.

The wizard Malygris lords over Susran, the capital of Poseidonis, but he has declined into hoary old age. His mind turns back to “the girl Nylissa whom he had loved in days ere the lust of unpermitted knowledge and necromantic dominion had ever entered his soul.” He asks his demon familiar to summon an image of Nylissa, but instead of finding comfort, he learns an unpleasant lesson about memory. In literature, memory usually carries warm nostalgia, but Smith constructs it here, as he does in the Zothique story “Xeethra,” as a trap. Malygris can love Nylissa in his memories, but his own soul has changed too greatly to recognize her real form when it appears. Although a brief tale, “The Last Incantation” has a theme relevant to all of Smith’s dying worlds: memory brings no solace to the corrupted, only the painful reminder of what corruption has forever placed out of reach.

“A Voyage to Sfanomoë”

“A Voyage to Sfanomoë”

Completed July 1930. First published in Weird Tales, August 1931.

In his second Poseidonis story, Smith seems uncertain exactly how he wants to portray this final vestige of Atlantis. “The Last Incantation” shows a world of sorcery, but here the backdrop shifts toward science fiction. One of the popular tropes in Atlantis fiction, which originates with Plato, is that Atlantis was the most technologically advanced civilization of its time. Smith embraces the concept here, but all of Atlantis’s scientific knowledge cannot halt the submergence of its last remnant, Poseidonis. Eventually the two greatest thinkers of Poseidonis, Hotar and Evidon, choose to escape the sinking island in their own spacecraft and fly to the planet Sfanomoë (Venus). Smith borrows a few ideas from H. G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon for the fuzzy science behind Hotar and Evidon’s globular vessel. The finale, where the scientists meet a bizarre but benign end, might have influenced science-fiction author Stanley G. Weinbaum’s own version of Venus in his classic story “Parasite Planet,” published a few years later, and it appears identically in the 2006 film The Fountain.

Although the story does not state it for certain, Poseidonis at last sinks beneath the waves during Hotar and Evidon’s flight, making this the terminal work of Poseidonis’ chronology. However, “A Voyage to Sfanomoë” ranks as a minor piece, interesting principally for its science-fiction elements; “The Death of Malygris” makes a more fitting finale for the short saga.

“A Vintage from Atlantis”

“A Vintage from Atlantis”

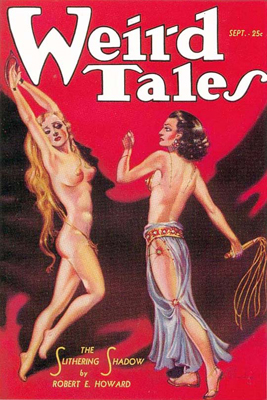

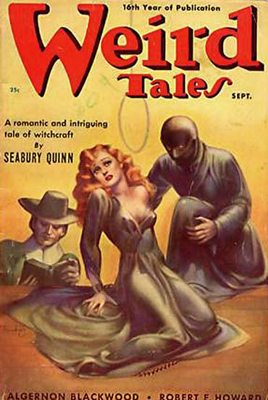

Completed 1931. First published in Weird Tales, September 1933.

This is an associational tale of Poseidonis that occurs in historic time, probably in the early eighteenth century during the golden age of piracy. Smith uses a device that appears in a number of his stories where the protagonist receives a memory implant of a lost era and feels compulsively and fatally drawn into it. This “false memory” plot works powerfully in “Xeethra” and “The Vaults of the Yoh-Vombis,” but Smith stumbles over his choice of backdrop in “A Vintage from Atlantis.” The setting feels disconcerting: Clark Ashton Smith telling a pirate yarn? Was he trying to lure in some of Robert E. Howard’s audience? His attempts at sea-dog slang in the mouth of Captain Red Barnaby sound stiff and often unintentionally funny, and the voice of the narrator, “Stephen Marbane, the one Puritan among that Christless crew,” comes across as stagy and unconvincing, too audibly the mouthpiece of Clark Ashton Smith’s style. Marbane relates how Barnaby’s crew discovers a massive, ancient flask of wine on the shore of an island where a storm has beached them. Red Barnaby declares the flask must have come from Atlantis, which is proved when the crewmembers drink from it (and force it on Marbane) and experience a vivid hallucination of the submerged civilization.

The name “Poseidonis” never appears, but the wine-induced vision contains the series’ most detailed description of how one of its great cities, probably Susran, appeared in its prime:

…great marble walls ascended, flushed as if with the ruby of lost sunsets. Above them were haughty domes of heathen temples and spires of pagan palaces; and beneath were mighty streets and causeys where people passed in a never-ending throng…. I saw the trees of its terraced gardens, fairer than the palms of Eden. Listening, I heard the sound of dulcimers that were sweet as the moaning of women; and the cry of horns that told forgotten glorious things; and the wild sweet singing of people who passed to some hidden, sacred festival in the walls.

“The Double Shadow”

“The Double Shadow”

Completed March 1932. First published in “The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies,” Auburn Journal 1933. Edited version published in Weird Tales, February 1939.

The events of this story, one of Smith’s finest, occur two generations after the wizard Malygris ruled Susran with his necromantic terror. Malygris’s final surviving pupil, Avyctes, has withdrawn from the world to content himself with scholarly studies in a marble mansion above the sea. His own student, Pharpetron, narrates the tale of the fate that befalls them when they unlock the magical secrets of a tablet of the extinct serpent-men that washes ashore near the mansion. After unraveling the cipher on the tablet, the two sorcerers use it to cast a summoning spell. The invocation appears to fail, but a few days later Pharpetron notices a second shadow tailing behind his master’s own: “its form was altogether monstrous, having a squat head and a long undulant body, without similitude to beast or devil.” Worse, the new shadow seems to creep closer to Avyctes’ real shadow with each day.

The power of the “The Double Shadow” comes from its clever magical curse that creates a tangible creeping doom and its excellent word-wizardry that shows the author doing what he does best: weaving literary magic with a perfectly selected choice of weird words. In lesser works, Smith could go over the top with his heapings of obscure diction, acting like someone flaunting his knowledge “Thesaurophical” (if you pardon me inventing a word). But when his muse was at its strongest and most inspired, he could create a work like “The Double Shadow,” which ensnares readers in otherworldliness from its opening and then sustains it without ostentatious distraction.

Although it does not directly deal with the fall of Poseidonis, the imagery of a “ravening” and destructive sea is potent in “The Double Shadow.” The writing keeps readers constantly reminded that Avyctes’ mansion lies perched over turbulent waters, and this instability heightens the tension and keeps the doom of Poseidonis at the forefront of a story of personal doom.

Smith must have had a fondness for this work, since not only did he publish it in his privately printed first volume of stories after it failed to sell, he named the whole collection after it. “The Double Shadow” would eventually appear in Weird Tales with some alterations, mostly small changes in diction and minor deletions. The major change is the omission of a paragraph that links “The Double Shadow” to the events of the two Malygris stories, and thus weakens the sense of a Poseidonis cycle.

“The Death of Malygris”

“The Death of Malygris”

Completed June-July 1933. First published in Weird Tales, April 1934.

The dark sorcerer Malygris returns, an uncommon feat for a Clark Ashton Smith character — although appropriately he returns already dead. Malygris’s adversary, King Gadeiron’s arch-sorcerer Maranapion, suspects that the tyrannical necromancer in his castle above Susran has died and kept his corpse intact to fool everyone into believing he still lives. Maranapion and the other great wizards of Poseidonis weave a magical plot to be certain of Malygris’ death. But the King and his loyal wizards learn that Malygris has found a way to extend his necromantic reach beyond death for a final act of terror.

Malygris appears more malignant here than the mournful old man in “The Last Incantation.” Since the sorcerer’s death was mentioned in the unedited version of “The Double Shadow,” that glimpse might have inspired Smith to tell the tale in full. This final Poseidonis chronicle has much in common with the Zothique series; it is filled with images of death, tombs, and putrescence. It is an appropriate end for the series: a dying civilization portrayed as withered corpses in royal robes scattered upon a black marble floor, the sole survivor an emerald adder slithering between the dust.

Mars

Mars has fascinated humanity since prehistory, and this fascination helped give birth to the genre of science fiction. Some of the earliest modern science fiction concerns voyages to the fourth planet of the Solar System, and the Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs are foundational works of the pulp genre. Smith first visited the Red Planet in “A Seedling of Mars” (also known as “The Planet Entity” and based on a plot from another author, F. M. Johnson) published in Wonder Stories Quarterly in 1931. This story has no connection to the Martian setting he would establish afterwards and is not considered part of the Martian science-fantasy mini-cycle that started with “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis.”

This story landed on the surface of Mars almost as an afterthought. Originally in Smith’s notes he had it occurring on a strange planet, like Xiccarph, but he altered it to Mars when he came to actually write the story. Steve Behrends suggests that the change was inspired by a recent brushfire near Smith’s cabin in Auburn, which the author noted in a letter to August Derleth had made the skies “as dark and dingy as the burnt-out sky of the planet Mars.”

In Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Martian novels, he indicated that the drying of the planet was gradually killing its civilizations; Mars was a dying world. Envision Burroughs’s Mars thousands of years after the death of its greatest civilizations, just as Earth colonists have started to arrive, and you have an approximation of Smith’s Mars. The difference is that the lost civilizations of this Mars are grim and gothic, hoarders of weird horrors unlike the adventurous wonders of Burroughs’s “Barsoom.”

The current inhabitants of Smith’s Mars call themselves “Aihai,” and have barrel chests, multi-articulated arms, high flaring ears, and pit-like nostrils. The best remembered of the dead civilizations, the Yorhi, have physical similarities to the Aihai but left behind sinister ruins and legends of their passing. The colonizing humans live primarily in the Martian cities, principally the trading port of Ignarh. The three stories follow the same plot outline: human explorers uncover a horror from Mars’ elder days beneath its red surface.

Smith had a negative experience selling these cocktails of interplanetary science fiction and weird fantasy, which may account for the series’ short life. The first two stories both had difficulty selling and underwent drastic revisions, one of them without Smith’s permission. Both works are now considered among the author’s best, which shows what potential died out with the series.

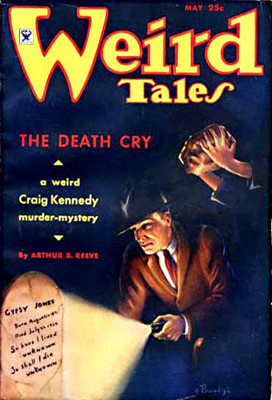

“The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

“The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

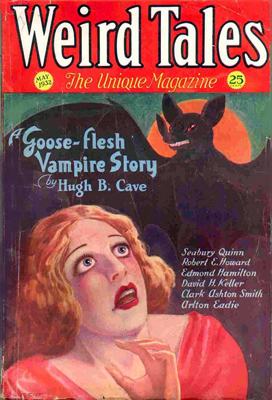

Completed August 1931. First published in Weird Tales, May 1932.

In a science-fiction pulp magazine like Planet Stories, this would have a title like “Brain-Sucking Leeches of the Red Planet.” It is an accurate plot description, but Smith’s customarily bizarre title, hinting of fantasy with the name “Yoh-Vombis” and horror with the mention of a vault, shows his eccentric approach to the Martian setting. The story demonstrates how the author could stew science fiction, fantasy, and horror into an unclassifiable brew.

From a Martian hospital, the sole survivor of a human exploration team tells about the terror that befell his companions after they set out from the city of Ignarh to explore the taboo ruins of Yoh-Vombis. The ancient city was built by the extinct Yorhi, whom the Aihai say died in a great catastrophe. The men enter the eerie ruins, and eventually find… well, please see my above alternate title.

Although there is more to the story than its terror — the aura of ancientness is palpable, and the ironic conclusion excellent — Clark Ashton Smith wrote few tales of pure fear superior to this, one of the best examples of the classic “weird tale.” It remains a genuinely frightening read today. In his introduction to the collection Xiccarph, Lin Carter held up this particular story as the ideal example of Smith’s peculiar genre niche. I concur: if I had to select a single work to introduce a new reader to Smith’s style and themes, I would pick this one without hesitation.

However, “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” went through a difficult period before it sold. Smith failed to sell a longer version to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales, and he cut about two thousand words before the editor accepted it. Most of the word casualties come from the establishing material at the beginning, and Smith later seems to have preferred the shorter version, since this was the one he submitted to anthologies of his work. Although the longer version provides interesting glimpses of the setting, the edited story feels more polished and moves faster at the opening to make the later horrors more potent. Changing the original version’s prologue into a postscript also adds a better “sting” to the finale.

“The Dweller in the Gulf”

“The Dweller in the Gulf”

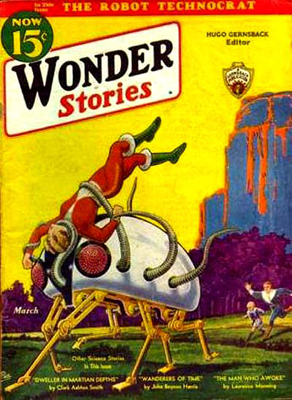

Completed August 1932. First published in edited form as “Dweller in Martian Depths” in Wonder Stories, March 1933. Unedited version first published in The Abominations of Yondo, Arkham House 1960.

Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales rejected this story, which Smith originally titled “The Eidolon of the Blind,” as too sickening for his readers, and Smith eventually had to sell it to Wonder Stories, a science-fiction magazine edited by Hugo Gernsback. Wonder Stories had provided a steady market for Smith’s more overtly science-fiction offerings like “The Master of the Asteroid.” For Gernsback to accept the story, Smith had to rewrite it to create more scientific justification for the events — exactly the opposite affect of what he wanted to achieve with these Martian stories. When the story finally appeared in the magazine it had undergone further changes not authorized by Smith, including a more positive ending. The incensed writer broke off his relationship with Gernsback, only selling one more story to the magazine seven years later.

The story ranks among its creator’s most grotesque, competing with the horrors of “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis.” (Smith considered “The Dweller in the Gulf” a “running mate” to the earlier story.) Human explorers in the Martian wastes again run afoul of a subterranean survival of the planet’s ancient days. Three gold-hunters in the empty region called the Chaur take shelter from a dust storm inside a cave. There they discover a corkscrew road swirling down into the stygian deep. A shuffling army of eyeless Martians forces the unlucky prospectors down the road to meet the horrible inhabitant who rules from below. The conclusion, which Smith proudly called “Dantesque” in a letter to August Derleth, is one of his most visceral and unforgettable. From the science fiction setting, Smith ably crafts something nearly infernal.

“Vulthoom”

“Vulthoom”

Completed February 1933. First published in Weird Tales, September 1935.

Once again, human explorers find weirdness beneath the rocks of Mars; this time, the mystery isn’t found in the taboo wastelands, but beneath its major city, Ignarh. Bob Haines, a former assistant pilot sacked from his job, and Paul Septimus Chanler, a science fiction writer, venture into the older area of the city out of curiosity in the exotica of Mars. A strange Aihai leads them to an underground complex where they encounter Vulthoom, an alien entity stranded on Mars who wishes to make an escape to Earth with the help of the two men. Neither wish to give it, and when an escape plan fails, they resort to more drastic measures the keep Vulthoom from bursting free to the surface.

As a more straightforward adventure tale, “Vulthoom” lacks the horror and atmosphere of its sister Martian stories, and the subterranean world where Haines and Chanler find themselves is not one of Smith’s better realized weird settings. Although weaker than its shivery companions, “Vulthoom” does provide a great deal of information about the life of humans on Mars and their co-existence with the Aihai. The dual nihilistic/heroic conclusion also works effectively, even though most readers will see it coming by the middle of the story.

Xiccarph

In a 1930 letter to H. P. Lovecraft, Smith described his predilection for completely invented settings: “I am far happier when I can create everything in a story — including the milieu. I haven’t enough love for, or interest in, real places to invest them with the atmosphere I achieve in something purely imaginative.” His planet Xiccarph, which lacks connection to anything terrestrial or historical, is the ideal realization of this concept.

Smith fashioned a number of extra-solar worlds as backdrops for one-shot stories, such as the planet Lophai and its tyranny of ghastly plant-life in “The Demon of the Flower.” In most cases, these planets exist to explore a single idea, like Lophai’s ecology of a humanoid race dominated by sentient plants, and are unsuitable as series settings. However, Xiccarph feels as if the author was developing a new cycle, his most bizarre yet. The character Maal Dweb plays key roles in both stories, and in “The Maze of the Enchanter” Smith gives a list of countries of Xiccarph that has enough variation to provide copious material for further tales:

Tiglari discerned in the throng the women of Ommu-Zain, whose flesh is whiter than desert salt; the slim girls of Uthmai, who are moulded from breathing, palpitating jet; the queenly amber girls of equatorial Xala; and the small women of Ilap, who have the tones of newly greening bronze.

It is a list to quicken the pulse of any fan of Clark Ashton Smith. What other phantasmagoric marvels might have arisen from this planet!

The two stories that did arise were written near the end of Smith’s principal fiction-writing phase, and when that concluded so did the promise of future Xiccarph chronicles. What the author might have done with the strange world and its infinite possibilities remains a mystery. But the two completed stories count among his most popular, and Lin Carter bequeathed the planet’s name to one of his Ballantine collections that re-introduced Smith’s work to the world.

The two works provide a few details about the planet. It has four small moons and rotates around a triple sun, giving it a short night. The abundance of sunlight may account for the overgrowth of dangerous vegetation, although there are hints of deserts and other arid terrain, probably near the equator. The civilizations of Xiccarph seem to be at a tribal level with Iron Age technology, with the exception of Maal Dweb and his “sorceries.”

Maal Dweb is the dominant force on the planet. “Magician,” “tyrant,” or “wizard” — exactly what he is remains purposely unclear. He rules over all the kings of Xiccarph through the power of his knowledge. Likely the knowledge is scientific, and Smith describes Maal Dweb’s extraterrestrial travel, genetic experiments, and advanced mechanics (the animated iron statues that serve him may be robots). But from the view of the people of Xiccarph and the readers, Maal Dweb is a wielder of magic. His powers are supernormal in the strict sense of the word, and the stories of Xiccarph are principally fantastic in tone.

“The Maze of the Enchanter”

“The Maze of the Enchanter”

Completed 1932. First published in “The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies,” Auburn Journal 1933. Published in an edited version as “The Maze of Maal Dweb,” Weird Tales, September 1938.

Smith held this story in high regard, since he had his unedited version printed in his self-published volume when he had difficulty selling it. The edited version that eventually appeared in Weird Tales makes a few deletions and changes, but is not significantly different. Either version counts as one of the author’s best and strangest works of fiction.

The apparent hero, the tribesman Tiglari, ascends the mesa where Maal Dweb dwells to rescue Athlé, a girl from his tribe, whom the tyrant has seized for one of his brides. Tiglari loves Athlé, although the warrior Mocari competes for the girl’s affections. As Tiglari slips into Maal Dweb’s abode, he discovers that Mocari may have also made the journey to rescue Athlé. Then the trap of Maal Dweb closes and thrusts the tribesman into the enchanter’s beautifully grotesque maze.

Smith had a particular love of describing unearthly plants, as in “The Demon of the Flower” and “The Seed from the Sepuclhre,” and he gives Xiccarph a luxuriant flora of grotesque proportions. The maze’s plants have sickening abilities, and Smith dives headfirst into this vegetative phantasmagoria:

The torturous maze became wilder and more anomalous. There were tiered growths, like obscene sculptures or architectural forms, that seemed to be of stone or metal. Others were like carnal nightmares of rooted flesh, that wallowed and fought and coupled in noisome ooze. Foul things with chancrous blossoms flaunted themselves on infernal obelisks. Living parasitic mosses of crimson crawled on vegetable monsters that swelled and bloated behind the columns of accursed pavilions.

“The Maze of the Enchanter” is an unusual work, even for its author. It defies the easy categorization of a hero; seeming to tell the story of Tiglari, who races to rescue a girl who may not care about him at all, it shifts focus at the end to the supposed villain, Maal Dweb. “Am I not Maal Dweb, in whom all knowledge and all power reside?” he asks, only to receive the unsatisfying Socratic “Yes, indeed” answer from the automaton at his side. Like Malygris, Maal Dweb learns that the pinnacle of power can be a lonesome place.

“The Flower-Women”

“The Flower-Women”

Completed 1933. First published in Weird Tales, May 1935.

This direct sequel to “The Maze of the Enchanter” makes Maal Dweb the main character — in fact, makes him into a hero of sorts. Still afflicted by ennui after the close of the previous story, the sorcerer chooses to make a journey to one of the other five worlds that circle the triple suns of Xiccarph. Using a dimensional cloud to travel to the planet Voldat, he discovers the vampire-flower women and then sets out to rescue them from the attacks of a race of reptilian sorcerers. The plot is a standard fantasy adventure, draped in weird extraterrestrial dross, and again abundant with floral imagery. It lacks the effect of “The Maze of the Enchanter,” but nonetheless is intriguing for two reasons.

First, it both expands and mystifies Maal Dweb’s abilities, whose powers sound more scientific, but receive overtly magical descriptions and titles. Second, “The Flower Women” presents the enticing possibility that Smith perhaps planned to make the Xiccarph series entirely about Maal Dweb — making it his first “character-centered” cycle. Maal Dweb survives the story, and his shift into a more heroic — while still morally ambiguous — mode indicates that Smith might have explored more cosmic gulfs and weird worlds with the character. However, by the time “The Flower-Women appeared in print, Smith’s main fiction writing period had come to end, and Maal Dweb would venture forth no more.

Postscript

Although Smith’s story cycles attract the most attention of his short stories, there are other treasures in his vault of weird prose. Previously, fans of the author had to buy various overlapping anthologies, many from out-of-print booksellers, in order to amass a reasonable collection of Clark Ashton Smith’s prose work. Fortunately, Night Shade Books has started a series of volumes that will collect all of Smith’s short fiction in chronological order, which will finally make his work available in an easily collectible format. Aside from his fantasy cycles, readers can discover his more traditional horror stories (“The Return of the Sorcerer,” “The Seed from the Sepulcher,” “The Gorgon”), strange romances, and straight science fiction (“Marooned in Andromeda,” “The Amazing Planet”).

This is the last of my articles on Clark Ashton Smith’s fantasy cycles, which started with the mundane French province of Averoigne and ends on the remote planet of Xiccarph. To conclude this last essay, I would like to draw attention to a story that fits in with none of the author’s cycles, “The Symposium of the Gorgon.” Smith wrote it in the last years of his life, and it captures the sorrow of an aging man who continually longs for the otherworldly, even when he has apparently found it. An unnamed man, transported by the winged horse Pegasus to a tropical island, accidentally becomes the god of the islanders. But it is not enough, this removal from the everyday, and the last paragraph — a single line — is a potent closure to Clark Ashton Smith’s life and work:

“I wish that Pegasus would return.”

You can read Part I of this series here, Part II here, and Part III here.

Our recent coverage of Clark Ashton Smith includes:

New Treasures: The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies, Vol. 1 by Clark Ashton Smith

Vintage Treasures: The Timescape Clark Ashton Smith

The Shade of Klarkash-Ton by James Maliszewski

One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith by Thomas Parker

New Treasures: The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

The Crawling Horrors of Mars: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

Deepest, Darkest Eden edited by Cody Goodfellow by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Adventures in Stealth Publishing: The Return of the Sorcerer

A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith by Matthew David Surridge

The Unqualified Unique: The Daily Mail Interviews Me for Clark Ashton Smith’s 50th Morbid Anniversary by Ryan Harvey

Of Secret Worlds Incredible: A Psychedelic Journey into Clark Ashton Smith’s Poetic Masterpiece by John R. Fultz

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part I: The Averoigne Chronicles by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part II: The Book of Hyperborea by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part III: Tales of Zothique by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph by Ryan Harvey

Ryan Harvey has lived most of his life in Los Angeles, although he attended Carleton College in Minnesota where he studied Medieval History, Classical Islam, and Film. He considers himself a full-fledged writer, with three completed novels, but has supplemented his income at various times as a speed reading instructor, reading development teacher, and magazine copyeditor. When not absorbing mounds of science fiction and fantasy literature and indulging in pulp, he swing dances wearing bizarre 1930s clothing. He also maintains his own website: The Realm of Ryan.

5 thoughts on “The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph”