An Interview With James Enge

By Howard Andrew Jones

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

When did you first create Morlock?

When did you first create Morlock?

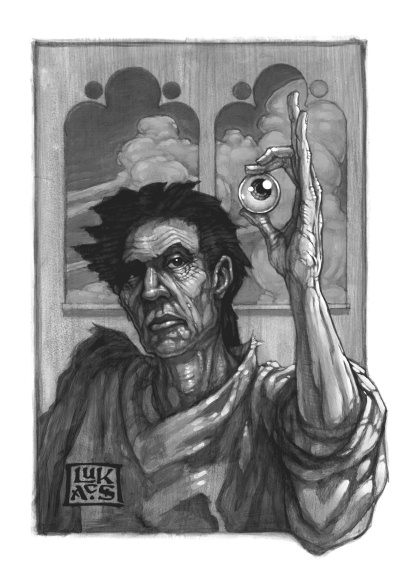

Morlock emerged in a massive and utterly immature novel series I was writing as a teenager. He appeared out of nowhere, and he was more interesting than the Lessingham-like hero, so when that series died from (my) boredom, I thought I’d write some about this Morlock Ambrosius guy. So I must have been writing about him as early as thirty years ago. He went through a major personality transformation in the late-80s, though. He had become a mopey Byronic wish-fulfillment self-image — what they call a Mary Sue, nowadays. So I took a big hammer and I smashed him until the faintest resemblance to me or my aspirations was gone. I’m wordy; he’s taciturn. I rarely drink; he’s a drunk. I couldn’t make a paper hat; he’s a master of makers. Things started to go better immediately after that, although it was a long time before he saw print.

The trigger for his genesis was reading H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine. I enjoyed it, but felt that Wells was not really giving the Morlocks a fair shake, much as Tolkien, in his depiction of Middle Earth, arbitrarily made Dwarves inferior to his favorites, the Elves. (Don’t get me started about Elves.) At the same time, some of the Arthurian stuff I was reading was full of names that sounded like Morlock (Morgan, Morgause, Mordred, Morholt). All these elements became connected in my mind, producing this Morlock Ambrosius guy, who was connected somehow both to Dwarves and to Arthurian legend.

Have you planned out his career in detail so that you’re able to write stories from any time period of his life?

Have you planned out his career in detail so that you’re able to write stories from any time period of his life?

I have his career blocked out, yes, so that I won’t shoot myself in the foot. I read the Hornblower stories in my youth, and liked them a lot, but since Forester wrote them out of order there are some glaring inconsistencies in the series, and I wanted to avoid that. Plus, both Zelazny and Poul Anderson say somewhere that it’s good for the writer to know more about the character than the reader does, so I figure my work on his biography isn’t wasted even if those stories never get written.

What about the rest of his world — how many of the lands and cultures have you mapped out?

I know Morlock’s world pretty well, some parts of it better than others. Most of the stories I’ve written so far are set in the central-to-western part of a continent called Laent, south of the divided Whitethorn/Blackthorn Range. There’s the Hidden Land (a high culture with no government, from which Morlock was banished) and the Second Ontilian Empire (an enterprise of his formidable sister, Ambrosia Viviana). Further east is the Anhikh Komos, which has some sort of government that Morlock dislikes. (He mentioned it, somewhat to my surprise, in “Payment Deferred,” Black Gate 9, and again in the upcoming novella “The Lawless Hours.” Someday I suppose I’ll have to figure out what he was talking about.) To the south of Laent is the continent of Qajqapqca, the home of the phoenix who comes up in “A Book of Silences” (Black Gate 10). North of the Blackthorn Range is a more shadowy area, a good place for Morlock to get in trouble.

I’ve heard rumors of Morlock novel — can you tell us a little about it? Is there any chance it will see the light of day soon?

After John bought “Turn Up This Crooked Way” for Black Gate, I decided that the next step was to write a Morlock novel. It’s called Blood of Ambrose (which may be too similar to Zelazny’s Blood of Amber). I’m currently flogging it to agents and any publisher who’ll take unagented queries. It’s set in a war for succession in the Ontilian Empire. Morlock’s sister, Ambrosia, has been ruling as a Richelieu-like power-behind-the-throne, but she’s getting a little old for the game and some sinister forces ally to destroy her. She calls on Morlock at a crucial point, and the trouble really begins. It has a trial by combat, a golem or two, zombie armies, demons, a flying horse, lots of crows, Morlock’s ex-wife and other things I thought were amusing. I hope someone buys it, because if not I’ll just have to write another one. (But I suppose I’ll do that anyway, given enough time.)

How many Morlock stories have you written? Do you have a definite number you intend to write?

How many Morlock stories have you written? Do you have a definite number you intend to write?

I just counted sixteen complete stories, aside from the novel, with any number of things in some state of incompletion. I don’t have any set number of stories planned, but I do have a sort of plot-arc in mind for Morlock’s career. When and if the major pieces depicting that arc are complete, the series would be finished. But I suppose that wouldn’t keep me from writing standalone episodes.

Tell us a little about your publishing history, and how long you’ve been writing?

I’ve been writing since I realized books were written by people. I was in no hurry to get published in the 70s and when, in the 80s, the magazine market began to turn away from the sort of adventure fiction I was writing, I had to decide whether to shape my fiction to appeal to the market or follow the promptings of my sordid Muse. I went with the Muse, which I still think was the right call, but it meant that the market had to change again before any of my stuff saw the light of day.

But now it has changed some, it seems. John O’Neill has bought five Morlock stories for Black Gate, including two pretty substantial novellas. And, of course, you, Howard, took three stories for the late lamented e-zine Flashing Swords: “A Covenant with Death,” which is still available at swordandsorcery.org, I believe; “The Red Worm’s Way,” which appeared in the Flashing Swords Annual, an e-book which doesn’t seem to be in “print” anymore; and “Green and Gray,” which also seems to have been lost in the foundering of the Pitch Black publishing empire.

This was a little upsetting to me: there’s no point in claiming a publishing credit for a story virtually no one has seen, but neither could I submit the story anywhere as unpublished. My solution to the problem was to set up a website where interested people can read “The Red Worm’s Way” on-line.

What are your writing habits? Do you outline? Do you work daily, have set hours, that you work each week, or some other method?

I admire writers who can keep regular hours, but I can’t work that way. Generally I daydream ineffectually about any number of stories that lie incomplete in my files. When one starts trying to chew its way out of my head, I pound it out on the keyboard as a less painful alternative. Then it’s back to daydreaming until the compulsion returns. I daydream a lot, so the compulsion is fairly frequent.

What other writing projects and characters are you working on?

I have written short sf/f that has nothing to do with Morlock or his world, but it doesn’t seem to have caught fire with anyone. My current big non-Morlock projects are a historical novel set late in the Roman Republic and a fantasy novel set in the Trojan War.

Who are your favorite authors? Your favorite specific authors who influenced you? What works of fiction most inspired you as a child?

This might take a while; stop me if I go on too long.

Reading Lord of the Rings when I was nine sealed my fate, I’d say. My first attempt at writing fiction was a ridiculous imitation of Tolkien (much like some people who had the misfortune to have theirs published). Lin Carter’s Ballantine series of classic fantasies opened up new worlds, too: Dunsany and Cabell became big favorites of mine. But without question the writers who cast the biggest spell on me (after Tolkien) were Zelazny, Le Guin and Leiber. Some of Zelazny’s Amber books appeared in Galaxy just after I discovered sf/f magazines, and they remain a high water mark in worldbuilding and storytelling in an American idiom. Le Guin’s science fiction had the earthy feel of fantasy, and A Wizard of Earthsea… is A Wizard of Earthsea. Leiber’s important to me for Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, of course, but also for works that intermingle the mundane and the fantastic: Our Lady of Darkness, A Specter Is Haunting Texas, “Catch That Zeppelin,” etc.

I love Jack Vance’s work, too, especially the Cugel stories. And I guess I have to mention Larry Niven’s Warlock series, especially “Not Long Before the End” and “What Good Is a Glass Dagger?” I dislike the hopelessness in them (a feature which began to poison Niven’s sf work in the late 70s and afterward) but I like the Warlock as a straight-faced worker of impossible wonders, and whenever Morlock pulls one of those bizarre fiery rabbits out of his hat, he tips the hat slightly toward Niven’s Warlock.

Some of my favorites aren’t influences on me — I don’t think they are, anyway: Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, for instance, or Norton’s Witch World books, or the classic (40s through 60s) sf I read as a youth and still reread. And Leigh Brackett’s sword-and-planet stories are a relatively recent enthusiasm of mine. As for writers who, you know, aren’t dead yet: I’m a big fan of Lois Bujold’s work — fantasy and science fiction.

I read a lot of narrative history, e.g. Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, and the ancient guys, especially Tacitus and Livy. About the same time I was dreaming up Morlock, I was reading and rereading Harold Lamb’s popular histories and biographies: Genghis Khan, March of the Barbarians, Babur the Tiger, the two volumes about the Crusades, etc. (That’s one reason I found Lamb’s Cossack stories so mind-blowing last year when I read the the first two volumes in your complete edition, Howard.)

I never laid my hands on Lamb’s biography of Tamerlane as a teenager, but when I was looking for it I came across Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, and was instantly addicted to his bombastic but brilliant poetic dramas. And I’m nuts about both Shakespeare’s Richard III and Kendall’s Yorkist biography of Richard, which is why Morlock has crooked shoulders and a monstrous reputation.

Then, too, I’m a big reader of mythology and epic. When I was a kid I must have read D’Aulaire’s Book of Norse Gods and Giants about a hundred times, and nowadays I frequently return to the great literary sources for European myth: Beowulf and the Old Norse sagas and narrative poetry, Vergil’s Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Dante’s Commedia, Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, Homer, of course (especially the Odyssey), the ancient novel. I was reading Apuleius’ Transformations of Lucius once when I thought, “Hey, I could use that bit in a Morlock story.” So I stole it (for “The Red Worm’s Way”).

T. S. Eliot is supposed to have said, “Immature poets imitate. Mature poets steal.” Assuming that the same applies to what we do, I’m proud to have attained maturity as a fantasist. Senility is obviously not far off, but as Leiber says somewhere, writing fantasy is one line of work where “being senile, even crazy, might help.”

Is there any place in particular from which you draw your inspiration?

Is there any place in particular from which you draw your inspiration?

Someone who makes universes should be legitimately interested in everything. I can’t quite live up to that standard, but I find that unexpected things become productive of fantasy. I was sitting around thinking about physics, once, and then I started wondering what would happen if Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle applied on a macrocosmic level, and pretty soon it turned into a Morlock story (“A Book of Silences”). Someone was explaining to me once how his family name had been misspelled as “lavabee” and I knew instantly that I would have to write a story with lava bees. (They appear in “Payment in Full,” an upcoming sequel to “Payment Deferred.”)

I have a theory that the secret source of fantasy is a failure to adapt to one’s environment. As human beings, we make our environments adapt to us, when we can, but we also learn to adapt to our environments when necessary. At the core of any fantasist or dreamer is a voice saying, “Yes, I know I could fly in one of those big noisy machines, but I wish I could fly like a bird. I know I can get money by working, but I wish I could change the rocks in my backyard into gold. I know that I can become famous by running for City Council, but I would prefer to slay a Dragon.”

Maladjustment is usually viewed as a bad thing, but the ability to dream about things as they are not may be related to the ability to change things as they are. Escaping briefly from the possible to the impossible may allow us to return with fresh eyes, to distinguish the way things as they are from the way we thought things were. How else can you get this kind of perspective on reality, except through fantasy?

Do you have any advice for aspiring authors?

I’m not sure I’m a good role model, but since you ask… It seems to me that writers should always be trying to reach their audience but, in doing so, should remember that they are part of the audience. No one can reach everyone, and a writer is most likely to move, amuse or otherwise interest that part of the audience who are moved, amused, or otherwise interested by the sort of things that the writer is.

Why do you think adventure fiction has had such a hard time of it in recent years?

I guess there are a number of causes. For one thing, there’s more competition: someone who likes fantasy adventure nowadays may be more drawn to gameplaying or media tie-ins than to fantasy fiction without prefabricated characters and worlds.

There’s a vicious circle effect, too: the less adventure fiction is available (I assume we’re talking about short fiction here), the less audience there will be for it: people will give up looking and find their entertainment in some other medium.

2 thoughts on “An Interview With James Enge”