Broken In Two: Poul Anderson’s Two Versions of The Broken Sword

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

A fierce warrior, magically born from a troll mother in the shape of a man, leads a troll army against the might of the elves. He stares at the troll king and mutters to himself: “I will succeed to your throne — but what good is that? What good is anything?”

A fierce warrior, magically born from a troll mother in the shape of a man, leads a troll army against the might of the elves. He stares at the troll king and mutters to himself: “I will succeed to your throne — but what good is that? What good is anything?”

Thus speaks Valgard, half of the protagonist of The Broken Sword. His words contain ambition contradicted with hopelessness. This utterance captures the overall tone of Poul Anderson’s influential fantasy masterpiece. Like the blade of the title, the novel is a collection of objects divided into separate, incompatible parts. Valgard is half of the protagonist, a tragic duo whose life plays out as a black joke from the gods. Heroes battle valiantly to spill the blood of their foes, but know that destiny will eventually eradicate them as if they never existed. The narrative sways between a realistic Norse setting inspired by historical sagas and a blurry faerie-realm of elvish wars. Finally, the text itself is snapped into two almost equal, yet intriguingly different, versions: the original publication, and the author’s own revision seventeen years later.

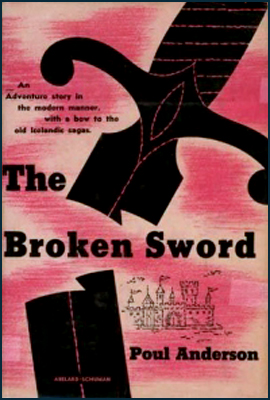

The Broken Sword, Poul Anderson’s first fantasy novel after establishing himself in science fiction, appeared in 1954 from publisher Abelard-Schuman. It received one lonely printing, and today a hardcover copy in good condition can fetch over two hundred dollars. Until British publisher Gollancz released a trade paperback reproduction in 2000 as part of its Fantasy Masterworks series, this first printing was the only way to experience the novel in its original format. Anderson revised The Broken Sword for the Lin Carter-produced Ballantine mass-market edition in 1971. He intended this rewrite to supplant the original, and it almost succeeded. The new edition turned into enough of a success to go through many reprintings through the ’70s and ’80s, and this version remains the one familiar to fantasy readers.

Yet even with the exposure from the mass-market edition, The Broken Sword is still not familiar enough. Published the same year as the first two volumes of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Anderson’s modern Norse saga heralded a new age in fantasy: what had once been a genre either of pulp action or “adult fairy-tales” in the style of Lord Dunsany was emerging as a mainstream literary form that could attract beyond a niche audience. It influenced in particular Michael Moorcock, who acknowledged borrowing the concept of a cursed sword that controls its owner for his popular Elric character. But The Broken Sword has received meager critical appraisal since its first publication, and almost nothing has been written about the editorial changes Anderson made for the better-known 1971 edition.

This article is a brief attempt to give credit to a classic that still lurks in the foggy fringes of fantasydom, as well as illuminate the difference between the two Broken Swords.

The Chill Winds of Fate

The Chill Winds of Fate

The cover of the first edition of The Broken Sword carries an explanatory subtitle: “An adventure story in the modern manner, with a bow to the old Icelandic sagas.” In tandem with the vague term ‘adventure story’ (which slights the fantastic elements), the phrase ‘modern manner’ appears to be a concession to potential buyers wary of a ‘stuffy’ or ‘old-fashioned’ work. The first edition had to sell to a generation of readers that knew fantasy only from pulp magazines — if they knew fantasy at all. Anderson’s introduction also makes excuses to its readers to provide a framework for what they are about to experience: “This is frankly a romance, a story of admittedly impossible events and completely non-existent places.” Tellingly, Anderson dropped this introduction for the second edition (except for an ambiguous concluding paragraph that sounds like a set-up for a sequel); 1971 readers no longer needed their fantasy worlds served with explanations. In the intervening seventeen years, a fantasy publishing boom made secondary world settings commonplace.

Anderson’s work can hardly be considered a ‘bow’ to Icelandic sagas, as the cover suggests. The chill air of the sagas blows through every aspect of the novel, from plot to language. The opening paragraph shows the tight bond between The Broken Sword and the literature of Iceland:

There was a man called Orm the Strong, a son of Ketil Asmundsson who was a great landsman in the north of Jutland. The folk of Ketil had dwelt in Himmerland as long as men remembered, and were mighty landowners. The wife of Ketil was Asgerd, who was a leman child of Ragnar Hairybreeks. Thus Orm came of good stock, but as he was the fifth living son of his father there could be no large inheritance for him.

This opening could have leaped from the first pages of the two most legendary Sagas of the Icelanders: Njál’s Saga (“There was a man called Mord who was also known as Mord Fiddle. He was the son of Sigvat the Red and dwelt at the farmstead called the Voll in the Rangá River district.”) and Egil’s Saga (“There was a man named Ulf, the son of Bjalfi and of Halbera, the daughter of Ulf the fearless.”). The Rangar Hairybreeks (Lodbrok) Anderson metnions is a legendary Norwegian king referenced in some of the sagas, so his inclusion in the first paragraph further links The Broken Sword to an elder literary tradition. Anderson also frequently inserts passages of original Icelandic-style verse, echoing the similar use of staves in the sagas, most particularly Egil’s Saga, whose protagonist is a renowned poet.

The only concession to modernity emerges in Anderson’s dabbling, in the style of Unknown magazine, with a pseudo-scientific justification for the elves’ fabled vulnerability to iron. This science-fantasy approach reflects the brand of fantasy that Anderson preferred in later works such as Three Hearts and Three Lions (1961), Operation Chaos (1971), A Midsummer Tempest (1974), and the historical naturalism of the “King of Ys” quartet (1986-1988, co-written with his wife Karen).

The elves (alvar in Old Norse) are central to The Broken Sword; Anderson treats them in the Scandinavian mythic tradition as a race of minor godlings, haughty and coolly removed from humanity. They have fine hair, high broad foreheads, strange slant eyes that are “cloudy blue without whites or a readily seen pupil,” and have “liquid, cat-like grace.” They have a proud self-centeredness, and even have scant care for their own children. Although Anderson points out in his 1971 introduction that his elves differ from J.R.R. Tolkien’s in their morally ambiguous nature, their beauty, dignity, and indifference toward humanity is identical, and the similarities of conception between the two authors will strike readers more than the differences. Both writers turn away from recent centuries of legend and literature where elf-kind appears as little more than fairy sprites who bathe in dewdrops, and instead look into the chill North winds to find an utterly inhuman race.

The story occurs in the eleventh century C.E. as Christianity spreads into the Northlands. The effect of the new religion on the Old Gods forms an important theme of the novel. The world has a dual nature: the mundane realm of humanity, similar to the lands of the historical, non-fantastic sagas; and the secondary realm of “faerie” invisible to humanity and indifferent to it. The realm of faerie contains not only Norse deities, but all supernatural beings of the older polytheistic religions. The spread of Christianity slowly weakens the lands of faerie, an idea Anderson also explores in the science-fantasy novel A Midsummer Tempest.

An early chapter brings Skafloc, a human raised in the elf-lands, face-to-face with an unexpected creature: a faun of Greek myth. The faun eulogies about the dying of the older religions before the coming the new:

“The priests cut down the sacred groves and built a church-Oh, I remember the dryads’ screams, quivering voicelessly on the still hot air and seeming to hang there forever. They ring yet in my ears. They always will.”

Anderson continues this unusual melding of pantheons throughout the book, introducing Celtic demigods and spirits to mingle with the Norse ones.

The story proper begins when the elf lord Imric kidnaps a human child, the son of Orm, and secretly replaces him with a changeling born from a captive troll-wife. The changeling grows up as Valgard Ormsson, a fierce and frightening man. Orm’s true son, named Skafloc by his elvish foster-parents, lives in Alfheim and thinks of himself as more elf than man. A witch with a feud against Orm and his family tricks Valgard into slaying his adopted father and brothers. The witch then reveals his true heritage to him, hoping to use the enraged changeling as a weapon against Skafloc. Valgard joins the trolls in their fight against the elves and his “true” self, Skafloc.

But the witch’s vengeance is a mere flurry before the blizzard. A full war explodes between the elves and trolls, and against this backdrop unfolds the tragedy of the Valgard/Skafloc opposition — the real vs. the counterfeit. Angry at the world for making him a soulless creature and a mere shadow of another man, Valgard fights a battle of desperation and confusion over his own identity. Even he cannot articulate the rage that propels him:

“I had naught against Orm or his house…. Yet I must have hated them, all of them, to have worked so much evil — on my own siblings — No — they are not my own blood, are they — were they?”

Meanwhile, Skafloc falls in love unknowingly with his own human sister, Freda, a devotee of the new faith of the White Christ. Skafloc wields a re-forged magical sword given as gift from the Aesir. The eldritch blade fills him with power and wrath but promises through prophecy to be his doom — or his “weird” in Anderson’s archaic usage. Behind the twists and turns lurks the hand of the Aesir working a mysterious destiny for the two men on which hangs the fate of the Old Gods.

With the exception of a slower passage where Skafloc searches for the giant Bölverk, who will re-forge the sword for the war against the trolls, the narrative of The Broken Sword moves in a perfectly choreographed dance of fate, much like the poetic description of a sword dance in Chapter 16, where injuries to the participants augur disasters to come. Tragedy compounds upon tragedy, and the grindstone of predestination continues to crush more victims. The Norns pull strands together and the tension and stakes rise higher and higher until the book reaches a nearly hysterical tone with the fate of Skafloc/Valgard and the gods teetering on the edge of a stark prophecy. The grim god Tyr warns, “More is at strake than elves or trolls know. The Norns spin many a thread to its end these days.”

At the conclusion of “The saga of Skafloc Elven-Fosterling” (as the book’s last line re-names it), when the victories and tragedies have played to their destined end, a sadder finale awaits beyond the final page, “when the powers of faerie fade, when even the Erlking shrinks to a forest sprite and then to naught…. man is fated to outlive the immortals.” Again, the similarity between Anderson and Tolkien runs deeper than some would imagine: “The deeds of men will outlast us, Gimli,” Legolas the elf remarks in The Lord of the Rings.

1954 vs. 1971

1954 vs. 1971

The 1954 version of The Broken Sword remains a spellbinding read, so why did Anderson rework it? In his introduction to the 1971 edition, he blames authorial distance for why he revised his earliest influential novel. He dismissively refers to his younger self who originally wrote the book as “someone else,” no longer in harmony with his writing style:

A generation lies between us. I would not myself write anything so headlong, so prolix, and so unrelievedly savage…. This young, in many way naive lad who bore my name could, all unwittingly, give readers a wrong impression of my work and me. At the same time, I don’t feel free to tamper with what he has done.

His solution is to revise the book in a way to make it “more readable” without changing the story.

I did not rewrite end to end…. Hence the style is not mine. But I have trimmed away a lot of the word brush, corrected certain errors and inconsistencies, and submitted one Person (in one brief though important scene) for another who really didn’t belong there.

However, it is often unwise to take an artist’s word about his work at face value. Anderson did write something equally savage and wordy in his last years, Mother of Kings (2000), which imitates the sagas closer than even The Broken Sword does. Anderson also gives the impression of a light editorial hand, but even a brief glance at his changes shows that he did “rewrite end to end,” making alterations to almost every paragraph.

Ninety percent of the revisions for the 1971 edition are minute edits and changes in diction. Paragraphs retain similar structures, but individual sentences are re-drafted. The following example, from Chapter 27/Chapter XXVII (the second edition uses Roman numerals for chapter headings instead of Arabic numerals), gives sketch of the changes made throughout:

Valgard stood on the highest tower of Elheugh and watched the gathering of his foes. His arms were folded on his great breast, his huge-thewed, black byrnied body was rock-still, and his face was as if carved in stone. Only his eyes lived, with a weird wolfish flicker far down in their chill depths. Beside him were the other chiefs of the castle and of the broken armies which now hid in this last and most powerful stronghold. Weary and despairing were they, wounded from cruel battles, staring with hollow fearful eyes at the hosting of Alfheim. (1954)

Valgard stood in the topmost room of the highest tower in Elfheugh and watched the gathering of his foes. His arms were folded, his body was rock-still, and his face was as if carved in stone. Nothing but his eyes seemed altogether alive. Beside him were the other chiefs of the castle and of the broken armies which hid in this last and most powerful stronghold. Weary and downcast were they, many wounded, and they stared fearfully at the hosting of Alfheim. (1971)

The original runs ninety-seven words, and the revision eighty-two. The 1971 version eliminates some of the extravagant descriptives, such as “the wolfish flicker” in Valgard’s eyes and his “black-byrnied body.” Other changes are substitutions of terms, such as “highest room” for “topmost tower.” The sense remains identical, but the feel of the second is cleaner, less cluttered — yet also less poetic. “I would like to think,” Anderson remarks in the revised introduction, “that the author would have been glad to have taken the advice of a man more experienced….” Envision an older Poul Anderson posed like a school tutor over a boy’s shoulder and crossing out extraneous words with a red pen in one hand and a copy of Strunk and White’s Elements of Style in the other.

It would require a full volume to catalog the changes and cuts made for the 1971 recension of The Broken Sword. The following table provides a short overview of the habitual emendations.

1954 |

1971 |

| struck a waiting, rippling melody from his carven harp | struck a chord on his harp |

| A few snowflakes drifted down through the silent bitter air. | A few snowflakes drifted down. |

| the screaming fury of a storm | a storm |

| A mighty longing rose in his breast and nigh choked him. | for a moment longing overwhelmed him. |

| In the desolation of a winter’s dream | At winter’s dawn |

| sullen and unspeaking | surly |

| A sudden fear, formless and ominous, sprang up cold in her breast. | A formless fear sprang high in her. |

| And she turned about and ran | She ran |

| Freda toppled from her saddle into darkness and his arms. | And he caught Freda in his arms. |

| scarce ever dream its like | scarce believe it |

The pattern tends toward simplification, but Anderson does not consistently pare down the older version. Less frequently, the revision expands the original:

| enmity | thwarting of your desires |

| laugh | know cheer |

| Tir-nam-Og | The Land of Youth |

| the deepest night-black dungeons | its deepest dungeons where toad and spider lurked. |

Many of the edits exchange one term for another or redraft the phrase without condensing or expanding it. The examples below are not global (i.e. both “glaive” and “sword” appear within the same version) but individual substitutions:

| glaive | sword |

| sea-weed | kelp |

| moon-rippling | moongladed |

| “Victory goes to the strong, in might or in guile.” | “The strong do as they please to the weak.” |

| ghost-silent | wordless |

| marriage | wedlock |

| mortals | common mankind |

| Skafloc’s face twisted, but he said naught | Skafloc’s mouth writhed, but he did not speak |

| angry | wroth |

| The Huntsman [referring to Odin] | The Wanderer |

| quoth | answered |

| traitor | backbiter |

| Bows twanged from the darkness inside | Bowstrings sang in the darkness behind |

| bounding and dodging | leaping and weaving |

| verses | staves |

| the gates were unlocked | the gate was unbarred |

Although Anderson makes numerous cuts, which would indicate an attempt to simplify the language toward a leaner, more contemporary feel, the substitutions reveal no such obvious modernization scheme. Select archaic words like “quoth” and “naught” are simplified, but others such as “staves” and “wroth” are added. Other changes show no significant shift, and this pattern begs the question: What did Anderson find deficient about the original? Since he is no longer alive to respond, readers can only assume that in the writer’s subjective point of view with seventeen years of hindsight, one version simply read superior to the other. Writers who have revised material after a long break can empathize with Anderson’s situation and understand why he made so many speciously trivial alterations.

Although Anderson makes numerous cuts, which would indicate an attempt to simplify the language toward a leaner, more contemporary feel, the substitutions reveal no such obvious modernization scheme. Select archaic words like “quoth” and “naught” are simplified, but others such as “staves” and “wroth” are added. Other changes show no significant shift, and this pattern begs the question: What did Anderson find deficient about the original? Since he is no longer alive to respond, readers can only assume that in the writer’s subjective point of view with seventeen years of hindsight, one version simply read superior to the other. Writers who have revised material after a long break can empathize with Anderson’s situation and understand why he made so many speciously trivial alterations.

Likewise, readers will have a subjective general reaction to The Broken Sword, Take #2. The text has changed, and although superficially the meaning remains identical, the book’s effect is altered, especially when read aloud. For example, look at another comparison, this one from Chapter 7/VII:

“I did not ask you to come,” said Ketil sullenly.

“No?” Valgard was still looking at the woman with his hard flat eyes. And she met his gaze, swimming in a sea of loveliness, and slowly her red mouth curved in a smile.

“You are a welcome guest,” she breathed. “Not ere this have I guested one like you.”

(1954)

“I did not ask you here,” said Ketil sullenly.

“No?” Valgard was still looking at the woman. And she met his gaze, and her red mouth curved in a smile.

“You are a welcome guest,” she breathed. “Not ere this have I guested a man as big as you.”

(1971)

The story content of the passages does not differ. But the rhythm has transformed, even with such simple switches as “one like you” for “a man as big as you,” and cuts like “slowly.” In a novel where poetry takes a central role, constant changes like this subtly alter the experience.

Based on the number of deletions in these examples, the 1971 version of The Broken Sword should end up shorter. However, the lengths of the two editions are roughly equal. This is because one of Anderson’s major revisions is additional information about battle tactics, history, geography, magic, and character motivations. The rewrite contains more historical details, such as a description of King Alfred’s victory at Ethandum and mention that churches are scarce because Vikings frequently put them to the torch, and particulars about the workings of Norse law and customs. The operation of supernatural forces receives greater explanations: Skafloc goes into detail telling Freda how shape-shifting works, and the inability of humans to properly see into the realm of faerie gets explicit mention. The erotic charge between Skafloc and Freda increases, perhaps because Anderson no longer felt wary of emphasizing a blatantly incestuous relationship as he might have in 1954.

Other changes smooth over transitions between sequences with better explanations or motivations for the characters’ actions. Chapters 10/X and 26/XXVI are the most changed in this way, involving different battle tactics in the former and specifics to clear up plot implausibilities in the latter. It feels as if Anderson anticipated readers’ nitpicks and tried to fix the logical problems.

The titular sword itself receives no proper name in the original, but is identified as “Tyrfing” in the revision, a name of mythic significance. It appears in the Poetic Edda as a sword crafted by the dwarves that would never miss its target, but cursed to take a life each time it is drawn-eventually that of its wielder. According the mythos used in The Broken Sword, Thor broke the weapon so it could work no more evil. Anderson may have always intended to identify the sword with Tyrfing, since the 1954 edition contains hints of its destiny and power, but he apparently later rethought the subtle approach and gave the sword its true name. He also provides a longer history of it through the mouth of the giant Bölverk, who re-forges the blade for Skafloc.

And what about this mysterious “Person” whom Anderson substitutes for another in one important scene? The answer exposes the greatest conceptual difference between the two Broken Swords: the treatment of Christianity. In the first edition of Chapter 6, the witch with a grudge against Orm’s family summons Satan to aid her. The Devil hints he has masqueraded as other “evil” deities, such as Loki, which seems to suggest the dominance of the Christian mythos. However, in the revised Chapter VI, Anderson removes the reference to Loki and appends a coda when the Devil leaves the witch’s hut:

…she peered after him, and what she saw departing was not what she had seen within. Rather the shape was of a very tall man, who strode swiftly albeit his beard was long and wolf-gray. He was wrapped in a cloak and carried a spear, and beneath his wide-brimmed hat it seemed that he had but a single eye. She remembered who also was cunning, and often crooked of purpose, and given to disguise in his wanderings to and fro upon the earth; and a shiver went through her.

Anyone familiar with Norse myths will recognize the witch’s visitor as the god Odin in his guise as the Gray Wanderer. In this single stroke, Anderson changes the mythic backdrop. The Devil does make an appearance in the revision, but only to tell the witch that she was duped into believing he had commanded her, when it was actually Odin. Not only does this fit better with the later revelation of the gods’ master plan for Skafloc and Valgard, but it lessens the importance of Christianity to a background force. Subtly throughout the 1971 edition, Anderson lessens the impact of Christianity. Freda, the most important follower of the new religion in the story, finds herself barely missing her faith as she falls deeper in love with Skafloc. Orm’s plans to build a church vanish. Odin, in disguise as the Devil, comments that the Christian “Heaven” leaves all creatures free will and takes no part in the pagan struggle. The faith of the White Christ presses against the realm of faerie and erodes it, but it isn’t central to the events of the war between the elves and trolls or the black destinies of Valgard, Skafloc, and the re-forged Tyrfing.

However, a major passage added to Chapter XIX puts philosophical perspective on the advance of Christianity, showing Skafloc pondering if Christians have found a way out of the endless cycle that will lead to Ragnarok, the fatal last battle of the Norse gods. The revision also weakens the powers of the some of the pagan entities, referring to Celtic deities as “godlings” instead of “gods,” and changing Fand’s formal address from “goddess” to “lady.”

However, a major passage added to Chapter XIX puts philosophical perspective on the advance of Christianity, showing Skafloc pondering if Christians have found a way out of the endless cycle that will lead to Ragnarok, the fatal last battle of the Norse gods. The revision also weakens the powers of the some of the pagan entities, referring to Celtic deities as “godlings” instead of “gods,” and changing Fand’s formal address from “goddess” to “lady.”

In a strange coda to all of the changes, Imric’s final musing that “man is fated to outlive the immortals” continues in the 1971 edition with a mournful judgment: “And the worst of it is, I cannot believe it wrong that the immortals will not live forever.”

Choose Your Weapon

The questions are hopelessly subjective, but anyone reading this survey of Anderson’s changes will want to know: Which Broken Sword takes the best approach? Which version should a reader choose?

The 1971 changes have much to recommends them: the reduction of the Christian influence is a thematically shrewd edit, and the greatest improvement Anderson made. The trimming of excessive description often makes the story more readable, as the author intended. However, the 1954 original has a more savage rush that feels even more “pagan” than the objectively less Christian rewrite. It is a rougher, more verbose, occasionally illogical work, but has a freshness not apparent in the over-thought second take on the material. Ultimately, not enough is objectively “wrong” with the original to merit a full-scale reworking. Perhaps the Devil made Anderson do it: the one scene where Satan manipulates the story had to go, and the author decided to change the whole book along with that one crucial sequence while he was at it.

The 1971 Broken Sword stands as a superb fantasy work on its own, but the warts ‘n’ all 1954 original, written by a young boy who bore the same name as Grand Master Poul Anderson, stands higher.

Here ends the Saga of Poul Anderson and the doppelganger Broken Sword. Scribe Ryan Harvey copied these words in his own hand from the heathen original. God have mercy on him, a poor sinner.

Very nice analysis. I pretty much agree with all you say. Anderson was a great influence. II advised Gollancz to publish the original and happily they did, so both versions are relatively easy to find. I’m not sure I see the context quite as you see it. I have been pushing this book ever since I read it (and also Henry Treece, who often captured the same atmosphere but was a much better writer) including my acknowledgements in various Elric editions. Anderson and Leiber were at least as important influences on me as Howard but the Norse sagas and eddas were my first and constant influences. The first two Elric books were described as SF by the hardcover publisher because fantasy still meant fairy tales to most readers and like LOTR and Gormenghast were rationalised by many reviewers as post-apocalyptic. At one point Tolkien and I had our own categories, especially in the UK, but slowly merged into SF&Fantasy as a genre developed. Had The Broken Sword been published ten years later, I suspect it would have been a best seller.

Dead Mr Moorcock,

you’ve mentioned Howard, Leiber and Anderson, but is it possible that you were also inspired by Henry Kuttner’s Elak of Atlantis?