The Wit and Wisdom of Connie Willis

|

|

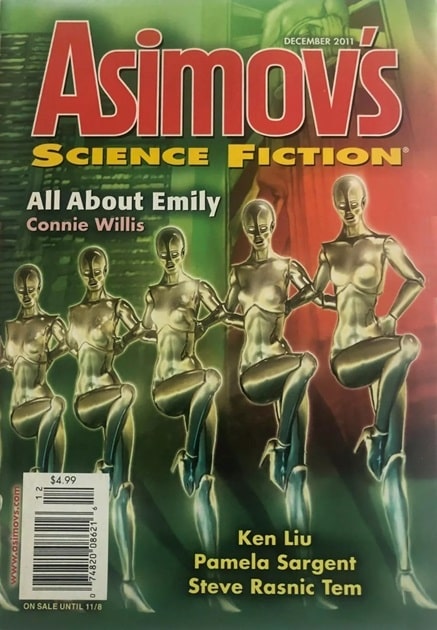

Asimov’s Science Fiction, December 2011, containing “All About Emily,” and the Subterranean

Press hardcover edition (January 31, 2012). Covers by Duncan Long and J.K. Potter

Far too often, the best among us are roundly ignored. This can hardly be said of Connie Willis, who has collected an astonishing array of Hugo, Locus, and Nebula awards, yet her name somehow doesn’t seem to ring from the battlements. Perhaps I’m simply attending to the wrong battlements, but when I hear discussions of the great women of science fiction, I tend to catch the names LeGuin, L’Engle, Butler, and, now, Jemisin. Willis seems to come up less frequently.

Better yet, let’s just leave gender entirely out of the equation.

Willis’s name deserves to come up front and center in any discussion of top-tier sci-fi, first and foremost because she is very funny.

Let’s face it: science fiction, despite the inescapable footprint of Douglas Adams, is not a genre known primarily for its humor.

And yes, any savvy reader can (and should) immediately dream up additional exceptions. But even as I concede that I’m painting with a broad brush, I believe that my point stands.

To Say Nothing of the Dog (Bantam Spectra,

January 1998). Cover by Eric Dinyer

Willis lets humor drive and motivate both her stories and her characters. Consider To Say Nothing of the Dog (or, How We Found the Bishop’s Bird Stump at Last), in which the crucial, indispensable object that everyone is searching for, the bishop’s bird stump, is never fully defined or described.

At best, it’s the sort of objet d’art that anyone with a modicum of taste would consign to a second-hand shop, and that, too, is part of the joke. The notion that a half-dozen dedicated, intelligent time-travelers are hunting desperately for a grail that’s nothing but an avatar of lousy taste proves to be half the fun.

Connie Willis

In truth, there are about a dozen other halves of fun to be had in To Say Nothing of the Dog, beginning with Cyril the bulldog, who chugs through the book like a stocky, drooling battering ram. Cyril drives the plot when it suits him, and takes naps when it doesn’t.

For the cat fanciers in the audience, there’s also Princess Arjumand, whose nine lives set the whole affair in motion, in large part because cats, in the future of 2057, where our heroes Ned and Verity hail from, are extinct thanks to a terrible bout of feline distemper. But there are plenty of cats in 1888, where Ned and Verity time-jump to seek the bishop’s idiotic and unknowable bird stump, along with enough mysterious Victorian behavioral tics to sink an Oxford punt.

Willis skewers the lot with wit, verve, and accuracy.

Anne Baxter as Eve Harrington in All About Eve

However, if satires of Victorian romance aren’t your particular cup of Earl Grey, there’s always the novelette, “All About Emily,” which announces itself on page one as an homage to Broadway and the Hollywood of yesteryear. The book’s more serious subject is the inherent labor problem of having a perfectly realistic robot take the role of Eve Harrington from the film All About Eve. Emily, a perfect ingénue in every way (except that she’s made of circuits), meets a Margo Channing type, a first lady of Broadway named Claire Havilland, and of course Claire initially chases Emily away, fearful that she and all other actors will soon be replaced by uncanny simulacrums.

But Claire has a change of heart when Emily falls in love with the Radio City Rockettes and sets out to audition. Willis makes the disconcerting argument that if a robot has even the least bit of choice built into its programming –– to choose to go this way or that way, to lift an object or put it down –– then that robot has at least a modicum of free will, in which case, it has rights. Human rights. And if robots have human rights, then they should be allowed to join the high-stepping Rockettes as a full-fledged, unionized member.

The Rockettes

My first encounter with Willis’s canon came years ago through “Even the Queen,” a sharp-edged short that made a clean sweep of that year’s Hugo, Locus, and Nebula awards, but apparently left some critics feeling betrayed. Willis takes swipes at various flavors of feminism throughout the story, starting early with this excerpt:

In the first flush of freedom after Liberation, I had entertained hopes that it would change everything –– that it would somehow do away with inequality and matriarchal dominance and those humorless women determined to eliminate the word “manhole” and third-person singular pronouns from the language.

I know a good many readers in today’s under-thirty set who would, on reading that paragraph, immediately consign Willis to the dustbin of writers we no longer need.

But they’d be wrong to do so. Willis’s ultimate targets are narrow-mindedness, the sort of rigid thinking that Paul Tillich labeled “demonic.” As Willis knows all too well (and martinets never do), where would we be without a certain levity to light our way?

So. For those who have yet to delve into Willis’s lengthy canon, you now have three wonderful, disparate entry points. Sally forth! Read for your life!

Onward.

Mark Rigney is a writer and long-time Black Gate blogger. His work on this site includes original fiction and perennially popular posts like “Youth in a Box.” His new novel, Vinyl Wonderland, arrives June 25th, 2024. A preview post can be found HERE, while his website lives over THERE.

The first Connie Willis I ever read was “The Last of the Winnebagos,” in which one of the plots is the extinction of domesticated dogs. It’s hard to wrap our heads around mass extinctions, but maybe easier to comprehend if we start by imagining the world without our omnipresent companions.

One of the highest compliments I ever got was at Mythcon, the day Tales from Rugosa Coven was awarded the Mythopoeic. One of the attendees praised the book as funny, and I demurred that I could not be compared with Douglas Adams. “Not Douglas Adams funny,” she replied, “but Connie Willis funny.”

High praise, indeed! And accurate, too.

My understanding is that Connie Willis is the most award-winning author in the history of science fiction and fantasy.

Yup. But, as I admitted up front, I’m not always on the “right” battlements––by which I mean that most of my friends don’t read much sci-fi, or pay attention to the vast literature that makes up speculative fiction. Black Gate’s readers are necessarily a more select group, and I suspect most readers of BG are at least aware of Willis, even if they haven’t read her work. But in a world of “upmarket book club fiction,” far too many have missed her entirely. Their loss, right?

My favorites among Willis’s main comic stories are probably still two of the earliest, “Spice Pogrom” and “Blued Moon”, from back in the ’80s. She’s delightful in her screwball comedy mode, but also capable of wrenching tragedy in stories like “A Letter from the Clearys” and “The Last of the Winnebagos” and the novel Doomsday Book.

I look forward to sampling more, and I appreciate those recommendations!